(Puppets)

Strings, Gloves, and The Art of Second Chances

The City That Keeps Secrets

Calcutta doesn’t bury its stories—it hangs them backstage, moth-eaten and waiting, until someone desperate enough yanks the cord. The city itself was an eternal stage, and its lanes were the cast—each corner playing a character, improvising from scripts written by necessity. The lanes held their own orchestra: hawkers calling “cha, muri, singara” into the rain-soaked dusk, the hiss of coal fires warming iron kettles, the metallic clang of tram bells echoing across Esplanade to Belgatchia, political graffiti, half-washed by monsoon water, still shouted Inquilab Zindabad from crumbling brick walls, all adding to the absurd theater of life. (Puppets)

In these streets, theatre and protest, hunger and art, rubbed shoulders so intimately that you could not tell where life ended and performance began.

Also Read: Cosmopolitan Club, Tagore, and UIUC: A Brief History of 100 years (Part: 1)

Most visitors remember this city for its grand performances—the thunderous applause at the Academy of Fine Arts when Utpal Dutt commanded the stage, or the way George Biswas could silence a roomful of murmurs with his searing renditions of Rabindranath’s songs. Or how an anti-fascist rally and its chorus could halt a crowded double decker bus with longing for freedom and justice.

Walk through any lane in the old city on a monsoon evening, when rain drums against roofs and the air smells of wet earth, and frying onions and fish, and you might hear it: the faint click-clack of wooden heads of the marionettes knocking together, the hushed rehearsal of ancient tales. (Puppets)

Fewer know that Calcutta was also where puppets learned to dance with the dreams of children who had lost everything. Where painted papier-mâché and scraps of sari silk became vessels of healing.

“It was 1952, and the man who would later be called the father of modern Indian puppetry worked sixteen-hour days, his hands always stained with paint, wood shavings clinging to his hair like flakes of snow.”

This is a story of three threads that tangled into something luminous: a master’s stubborn vision, a young woman’s devotion to that vision, and a circle of orphaned children who discovered that sometimes salvation comes dressed as play.

The Master’s Workshop

In the cramped office at 6 Hastings Street (now Kiran Shankar Roy Road), Raghunath Goswami was remaking an ancient art. It was 1952, and the man who would later be called the father of modern Indian puppetry worked sixteen-hour days, his hands always stained with paint, wood shavings clinging to his hair like flakes of snow.

Goswami had founded Puppets Calcutta with an audacious dream: to prove that folk puppetry could hold its own against cinema, enlightening the masses with stories that were waiting to be told. His workshop was a forest of marionettes dangling from the ceiling like sleeping angels, their strings like vines connecting separate lifetimes. The painted faces caught the glow of bleak incandescent lamps. The smell of varnish and turpentine mingled with the sweet smoke of incense burned for Saraswati, goddess of arts and enlightenment. (Puppets)

“Swapna Sen first climbed the narrow stairs to Goswami’s workshop in 1965, a young woman with paint-stained fingers and fire in her eyes. She had studied fine arts but found canvas and pigment too static.”

By 1960, his great experiment arrived: Hattagol Vijay, India’s first puppet film. The story of a clever elephant who outwits his enemies instead of force captured the imagination of children across the nation, even winning the Prime Minister’s Gold Medal for Best Children’s Film. Suddenly, puppetry wasn’t just rustic entertainment—it was art capable of tears, laughter, and wonder.

But Goswami knew something deeper: art only endures when passed from one pair of hands to another. He began searching for disciples who could carry the flame forward into an uncertain century, one that would merge seamlessly with the dream Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru was envisioning with fateful certainty—an independent, free India, fresh out of the clutches of its colonial masters. (Puppets)

Also Read: Books That Burst Out of Windows and Spiral Into Infinity- Part 1

The Disciple Who Became a Bridge

Swapna Sen first climbed the narrow stairs to Goswami’s workshop in 1965, a young woman with paint-stained fingers and fire in her eyes. She had studied fine arts but found canvas and pigment too static. When she saw Goswami’s puppets come alive—when papier-mâché seemed more expressive than living actors—she knew she had found her path.

For three years, she apprenticed under the master. She learned the ancient secrets of making puppets, and voice modulation that could make a wooden prince sound noble or a cloth monkey sly. Her hands grew skilled at carving and painting, but more importantly, she absorbed Goswami’s creed: puppetry was not mere diversion but a form of healing, a way to process grief and joy at a safe remove. She didn’t just learn technique—she learned to read a puppet’s weight the way a doctor reads a pulse. (Puppets)

Goswami recognized in her something rare—not just craft, but the teacher’s instinct. “The puppets speak through you,” he once told her as they worked late, untangling the strings of a stubborn marionette, “as if they were your own children.”

“The puppets spoke, but no one spoke back. She was looking for the place where the strings would change hands—where the voiceless would find their voices through borrowed mouths.”

By 1968, Swapna began branching out, performing at schools and community centers, searching for a place where puppetry could do more than entertain—where it could transform. For nine years she moved through Calcutta’s educational landscape like a cartographer mapping unmarked territory. She performed in government schools where children sat cross-legged on concrete floors, in private institutions where puppet shows were considered quaint diversions between algebra lessons, in community halls where adults watched with the guilty pleasure of reclaimed childhood.

But something was missing. The children laughed, clapped, went home. The puppets spoke, but no one spoke back. She was looking for the place where the strings would change hands—where the voiceless would find their voices through borrowed mouths. (Puppets)

The Village at the Edge of the City

The call came in early 1978 from the city’s far edge, where chaos loosens into air. SOS Children’s Village had opened its gates in Calcutta the previous year. The organization arrived like a foreign language the city slowly learned to speak—orphanages reimagined as clusters of homes where “mother” wasn’t biology but vocation. Hermann Gmeiner’s post-war Austrian model, born from the wreckage of World War II in Innsbruck, had traveled poorly at first; Indian bureaucracy nearly strangled it in red tape. But the village took root, offering shelter to children the world had discarded.

“Psychology textbooks offered theories; what they needed was someone with puppet heads and a hunch that sometimes healing speaks through mouths that aren’t their own.”

The administrators understood shelter. They grasped nutrition, schooling, routine. What baffled them was how to coax trust from children who’d learned that trusting gets you abandoned. (Puppets)

They knew they wanted something that would unlock these children, but had no map for what that might look like.

When Goswami came across the administrators calling for volunteers, he knew instantly. He thought of his disciple.

Also Read: Remembering Munshi Premchand

Psychology textbooks offered theories; what they needed was someone with puppet heads and a hunch that sometimes healing speaks through mouths that aren’t their own.

“This is what you were meant for,” he told Swapna. “These children need puppets—voices that will speak what they cannot.”

So one monsoon afternoon in 1978, Swapna arrived with a suitcase of puppet heads, paint pots, and possibilities. She had no plan but Goswami’s mantra: Start where their hearts are. Let the stories rise from there.

The Boy Who Found His Voice

Among the children was a twelve-year-old boy, fatherless now, learning too early how absence of only one person can hollow out a life. He drifted like a ghost through his days—speaking little, turning away whenever adults asked about his feelings. The others found comfort in sports, music, drawing. But he remained adrift—a pronoun in search of a name. (Puppets)

“The children laughed, shouted advice, and for a moment their laughter drowned the wounds that clawed at them—the reminder that they were still orphans, still strangers to the mainstream of life.”

Adults had already written him off with careless labels. One teacher muttered he was “slow,” another thought him obstinate. None saw the storm of words building inside. Silence was not emptiness for him—it was a room without doors, where he wandered alone, unheard, unseen.

Until the day Swapna set up her black curtained booth in the main open-air pavilion.

She brought only a glove puppet: a monkey with mischievous eyes and a red velvet vest. Slipping it onto her hand, her voice brightened into play. “Hello, children,” the monkey chirped. “My name is Buddhu, and I am terribly confused. Perhaps you can help me?”

The children laughed, shouted advice, and for a moment their laughter drowned the wounds that clawed at them—the reminder that they were still orphans, still strangers to the mainstream of life. They were simply children watching a silly monkey stumble through imaginary predicaments. (Puppets)

“They knew this boy never spoke, never volunteered, never breached his self-imposed exile from the realm of sound.”

Twenty minutes into the performance, a hand rose from the back row—tentative as a seedling pushing through cracked pavement. The other children turned. They knew this boy never spoke, never volunteered, never breached his self-imposed exile from the realm of sound. Swapna paused mid-sentence, letting the moment crystallize, a bead of dew caught on the edge of a blade of grass:

“Yes?” she asked, the monkey’s head tilting with exaggerated curiosity.

Also Read: Keeping Emergency Memories Alive

The boy stood. Walked forward. Reached out his hand.

The other children’s stares had weight. I’d spent years perfecting invisibility, moving through rooms without displacing air, but now my body betrayed me with wanting. When I reached out, my fingers were shaking. The cloth was warmer than I expected—Swapna Maasi’s hand had left its heat there. I slipped my hand inside and felt the monkey’s head settle onto my knuckles like a crown, like permission. When I opened my mouth, the voice that came out wasn’t mine—it was truer than mine: I am lost. I am looking. I am still here.

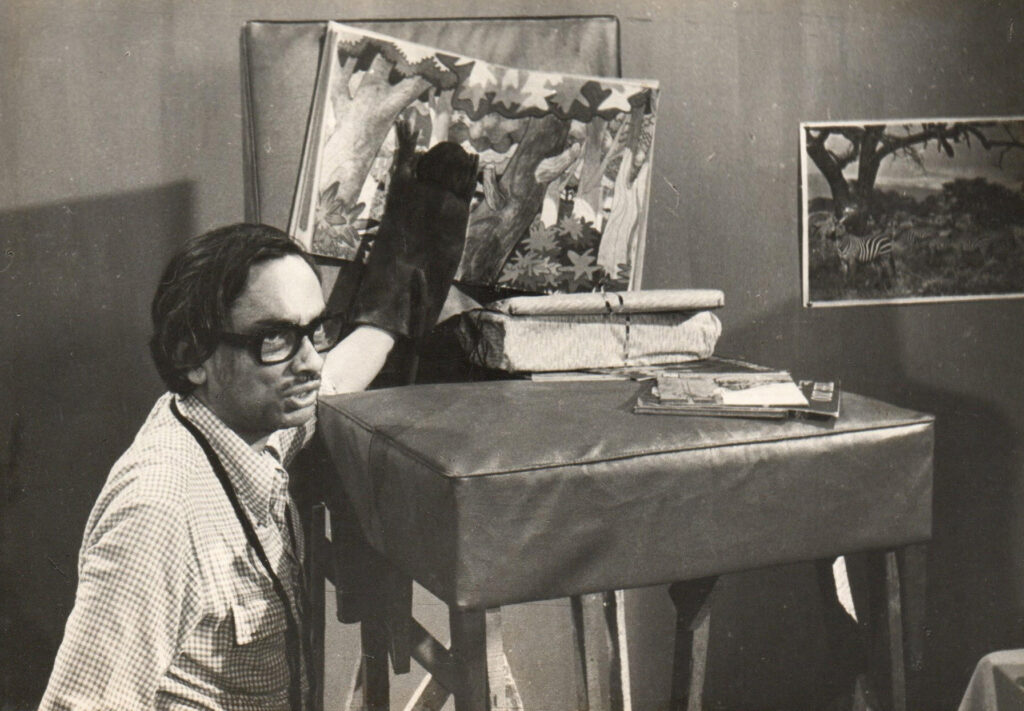

Photo Courtesy: Youtube, Bengali Film Archive

Gunjon Dasgupta writes about power, technology, and the cost of justice. His work includes The Ananya–Rudra Series, a political thriller, and essays bridging Ambedkar's moral philosophy with contemporary political economy. He lives in Kolkata.