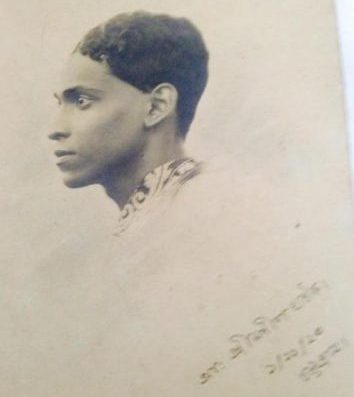

My grandfather Manish Ghatak was born on 9th February in Rajshahi in 1902. A poet, short-story writer, and novelist, he was one of the pioneers of the neo-realist tradition in Bengali literature. As a student in Presidency College, he was introduced to Gokul Nag, the editor of ‘Kallol’ magazine, quite by chance. In his autobiographical book ‘Mandhatar Babar Amol’, he writes that he was, back then, a tennis and a hockey player who also loved literature but had not thought of writing himself.

Quite accidentally he bumped into Fazal, a pickpocket; Fazal’s abortive attempt at picking Dadu’s pocket in College Street while he was visiting a favourite second-hand bookstore led to an unlikely friendship. Fazal introduced him to the underbelly of society, a world hitherto unrepresented in Bengali literature. He chose to write about Fazal’s world, under the pen name Jubanashwa. Yet he was equally comfortable writing about what would now be called the cultural and social elite, as he did, for example, in his novel ‘Kankhal’.

In the Puranas, Jubanashwa was the father of King Mandhata. In Bengali, the phrase “Mandhatar amol” (Mandhata’s times) denotes outdated or antiquated times. In his usual style, Dadu named his semi-autobiographical novel ‘Mandhatar Babar Amol‘ (literally, Mandhata’s father’s times)! He went on to write poems, short-stories, and novels, and founded and edited a little magazine called ‘Bartika’ until his death. I am likely to be biased, but I find Dadu’s style very elegant, witty, and minimalist. His collection of short stories ‘Pataldangar Panchali‘, was based on the lives of the poor and marginal classes, a world that Fazal had introduced him to. It created quite a furore in the literary scene of Bengal; some found its contents to be indecent while others hailed its bold realism.

Even though Dadu was not directly associated with any political party or movement, many of his poems, especially in the later stages of his life, had a clear radical edge, ranging from protest to satire. His literary legacy, including the focus on the poor and the underprivileged as well as an explicitly anti-establishment flavour, was carried forward by his daughter, Mahasweta Devi, and her son, Nabarun Bhattacharya, both very distinguished writers in Bengali.

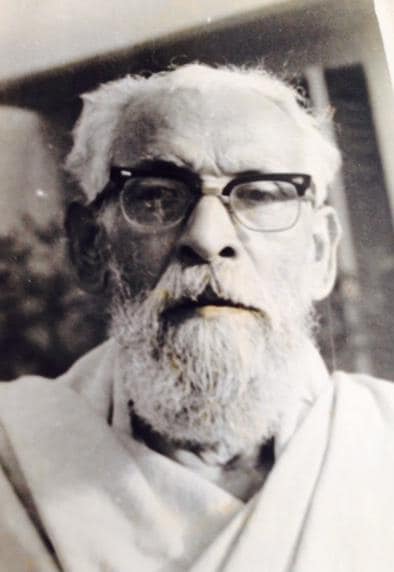

Dadu’s father Suresh Chandra Ghatak was a district magistrate. Dadu was his eldest child, and Ritwik Ghatak, the filmmaker, was the youngest. Dadu spent his life as an official in the income tax department and even after his voluntary retirement in 1952, continued in an advisory capacity till the 1970s. His imposing height, sense of humour, and frank and disarming personality made him stand out in literary circles, as touchingly documented by tributes paid after his death, such as a reminiscence by the distinguished essayist Sudhir Chakrabarty who was close to him (and who himself passed away recently). The Ghatak household of Berhampore was well-known for its cultural and literary ambience. I have read about his friendships with many eminent writers of Bengali literature and some of them are mentioned in ‘Mandhatar Babar Amol‘.

The eminent poet and essayist Sankha Ghosh spoke warmly to me about meeting Dadu in a literary conference in the 1960s and how approachable he was to young writers and poets, with his ease of manner and ready sense of humour.

I did not see Dadu in his glory days and in my memories of him, his health was already failing, and he lived a somewhat monastic life. Still, as a boy I remember meeting poets such as Shakti Chattopadhyay who would always visit Dadu when he was in Kolkata. I remember meeting Beerendra Chattopadhyay in Berhampore; he was very close to Dadu and the one who motivated him to publish his translations of poems by Neruda as a book in 1974, much before Latin American literature became popular in Bengal’s literary circles.

The eminent poet and essayist Sankha Ghosh spoke warmly to me about meeting Dadu in a literary conference in the 1960s and how approachable he was to young writers and poets, with his ease of manner and ready sense of humour. In 2004, I happened to participate in a panel discussion with the distinguished novelist and sports journalist Moti Nandi, whose warmth was palpable when he connected me to Dadu and told me how indulgent and affectionate Dadu was to younger writers like himself.

My grandmother Dharitri Devi (after whom our house in Berhampore was named “Dharitri”) was extremely well-read and highly opinionated. She hailed from the well-known Chaudhury family in Dhaka; her illustrious siblings included Sachin Chaudhury, the founder-editor of the Economic Weekly (later the Economic and Political Weekly), and Sankho Chaudhuri, the sculptor. Thakuma, as I called her, did not think well of any writer other than Rabindranath Tagore and was not shy about voicing her opinion. The banter between my grandparents was legendary.

I was named by Dadu and my mother recalls the funny story behind it. Apparently, Dadu would propose a name (starting with the letter M, given that his name and the name of my father, Maitreya, started with it) and Thakuma would immediately reject it. Eventually she agreed to the name “Maitreesh,” apparently thinking that it was my mother’s father, of whom she was very fond, had chosen it! I was Thakuma’s pet and my early taste in literature was formed largely by reading out books to her as she had lost her eyesight by then.

Some of my happiest memories are of Berhampore, Murshidabad, where my grandparents lived. My cousins, my brother, and I would spend our vacations there, and we were always up to some mischief. Some of this is stuff of legends, stories I regale my daughters with.

Dadu passed away in 1979. Life was never the same again. The last time I went back to Berhampore was in 1993 but it is still very much in my thoughts.

Here is my translation of one of his lesser known poems, written in 1978, which seems to resonate well even after all these years:

Leches will leer and crooks will steal

With rule of law, they’ll land in jail.

When they’re the ones in power though

In which court do we appeal?

You can read the original Bengali poem here:

“লোচ্চারা লোচ্চামি, চোরে চুরি করবেই,

শাসক সবল হলে হাতে দড়ি পড়বেই,

কিন্তু তারাই যদি

পাকড়াও করে গদি

কোন কোতোয়ালে বল তখন খবর দেই?”

নীতি পাঠমালা #১১, অগ্রন্থিত কবিতা, মণীশ ঘটক রচনা সংকলন, দ্বিতীয় খণ্ড।

Reference:

- Manish Ghatak Rachana Sankalan, Volumes 1 and 2, edited by Soma Mukhopadhyay, Dey’s Publishing, 1994.

- Image courtesy: Tinnie Mukherjee

- Complete list of books by Manish Ghatak: ‘Pataldangar Panchali, Kankhal, Shilalipi, Jodio Sandhya, Bidushee Bak, Jubanaswer Neruda, Ekchakra, Mandhatar Babar Amol.

- Mahasweta Devi writes about her father Manish Ghatak in her autobiographical essay ‘Tutul’.

- Manish Ghatak on Wikipedia

One Response

” If I have seen further, it’s by standing on the shoulders of giants. ”

— Newton to Hooke (alluding to Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, & Brahe). Intellectual forebears, even though from different disciplines (albeit The Romantic Economist)….and a family-affair: Oeuvre !!