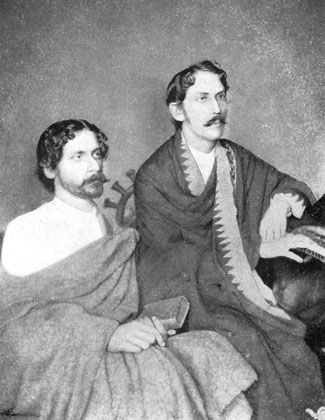

Interrupting his journey to London, Rabindranath went to Mussoorie to meet his father in 1881. Probably unable to bear the wrath of his family members who were naturally disappointed with his truncated journey to London, Rabindranath came to Chandernagore where his ‘Jyoti dada’ and ‘Notun Bouthan’ were spending time at ‘Riverview’. Mallika Sengupta in Kabir Bouthan (2011) brilliantly captures the endearing moments Rabindranath spent with his brother and sister-in-law:

“Thakurbarir kolahol theke dure gangar kole sei bari jeno ek swapnorajyo”(226)

[Far from the exasperating crowd, the swarm and rabble of Thakurbari, this house is like a floating loop of illusion in the kingdom of dreams]. Drenched in the rain, the natural green and the Hooghly river looked mesmerising to a young Rabi and inspired him to indulge in creativity. In Chelebela, Rabindranath recalls:

“Natun barsha nemeche. Megher chhaya bheshe choleche sroter upor dheu khelie, […] anekbar eirakom dine nije gan toiri korechi, sedin ta holo na. Vidyapatir podti jege uthlo amar mone, ‘e bhara badar mah bhadar, sunyo mandir mor’…” (‘Rabindra Rachanabali’, 733)

[The first rains had just fallen. Cloud shadows lay dark upon the jungles of the further shore. I had often composed songs of my own on such days, but that day I did not do so. The lines of Vidyapati came to my mind].

Interestingly enough, it is Jyotirindranath who first heard Rabindranath’s tune and imparted proper notations to it. Sadly enough, Prasanta Kumar Pal didn’t mention this in ‘Rabijibani’,Vol II. Nevertheless, the film ‘Kadambari’ (2015) entraps the moment of elation when Rabi’s melodious voice coalesces with the sound of raindrops falling on earth, the blithe wind blowing past Kadambari and Rabi, as if nature has participated in ushering the season of rains.

In the midst of these carefree, indolent days, Rabindranath learnt the niceties of translation from his Jyoti dada. In fact, Rabindranath grew up in an ambience where cultivation and appreciation of French literature was a common phenomenon:

“Bastuto Thakurporibare forashi bhasha-chorchar ekti dirgho oitijhyo purbei gore uthechilo – Satyendranath, Hemendranath o Jyotirindranath ei bhashay bishesh paradarshita arjon korechilen, emon ki Francer Nice shahare bash korar somoy e Jyanadanandini Debio Ollendorf-er boi er sahaytay kathabarta chalanor moto forashi bhasha sikkha korechilen, e katha tnar atmakathay ullekh korechen [Puratani 41]” (Pal, ‘Rabijibani’, Vol II, 148)

[The practice of French language was a tradition in the Tagore family – Satyendranath, Hemendranath and Jyotirindranath attained scholarly knowledge and expertise in this language. Jnanodanandini Devi, while staying for a few days in the city of Nice in France, learned to communicate in French with the help of the book of Ollendrof – she herself has recorded this in her autobiography Puratani (41)].

Moreover, Jnanodanandini Devi’s daughter, Indira and Indira’s husband, Promotho Chowdhury were also renowned scholars in the Field. In ‘Thakurbarir Andormohol’, Chitra Deb mentions Indira Devi as the first Bengali woman to have learnt French language along with English during her graduation in 1892 (Deb 113). Indira Devi has meticulously translated Rene Gruse’s ‘Bharatborsho’, Madame Levi’s ‘Bharat Bhromon Kahini’ and Andre Gide’s ‘Forasi Geetanjalir Bhumika’ into native Bengali (Deb 115).

Apart from his family members, Rabindranath’s friend, Priyanath Sen was a distinguished scholar of French language along with English and Bengali and in his company he practisd his French.

“Rabindranath er pokkheo forashi bhasha-charchay agrahi hoe otha asambhab chilo na ebong hoyto kichuta paradarshitao arjon korechilen”(Pal, Rabijibani,Vol II,148)

[It is not at all astonishing, that in his company Rabindranath would be interested in practising French and perhaps he also achieved some excellence]. To Rabindranath, Sen was “Sahityer Sat Samudrer Nabik tini’’ (qtd. in Pal, ‘Rabijibani’, 137)

[He is the Sailor of the Seven Seas of Literature].

As registered in the essay “Forashi O Bharatiya Krishti O Bangla Sahitya” published in Chandernagore College Magazine, 1957, Professor Sree Debendranath Chattopadhay notes that Dr. Kalidash Nag, an eminent French scholar was a close associate of Tagore. Though no records can be found on whether Tagore and Nag met in Chandernagore during the former’s multiple stays there, they knew each other very well and Nag translated Tagore’s ‘Balaka’ into French. Already a part of an informal network of Francophone artistic expressions, Rabindranath was further motivated to continue with cultivation of the French language through the translations from French into Bengali by Jyotirindranath done at Chandernagore.

The four poems of the French romantic poet, Victor Hugo, which were translated into Bengali by Rabindranath at Chandernagore were named as ‘Kavi’ (‘The Poet’ / ‘La Poete’, 1860), ‘Bisarjan’ (‘The Immersion’/ ‘15 Fevrier’,1843), ‘Tara o Ankhi’ (‘The Star and The Eyes’ / ‘Heir Au Soir’ 1853) and ‘Surjo O Ful’ (‘Sun and Flowe’r / ‘Unite’, 1855). These poems are included in ‘Prabhat Sangeet’ (1883), Paschimbanga edition of ‘Rabindra Rachanabali’.

From ‘Rabijibani’ (Vol II, 149) one comes to know that contrary to these successful translations, Rabindranath also failed at translating two other poems of Hugo, namely ‘Aimons tonjours! aimons encore’ and Qui pulvis ES, which he named as ‘Bhalobasha’ and ‘Jibon Moron’ respectively. There arose a controversy centring the credit of translation. In his essay, “Rabindranather Forashi Charcha” (Desh,1970,851-60) [“Rabindranath’s Practice of French Language”], Dr. Bhudeb Chowdhury, Retired Professor at Visva Bharati, accepts the translations as Rabindranath’s and expresses his elation in declaring Tagore’s triumphant acquiring of the French language. To substantiate his claim, Chowdhury quotes from Priyanath Sen’s essay ‘Guy de Maupassant’ where Sen in the footnotes guides the readers to Tagore’s ‘Prabhat Sangeet’ and especially to the two poems ‘Tara o Ankhi’ and ‘Surjo O Ful’ and renders

“[…]Banger sarbosreshtho gitikobi ascharya pratibhabole, asadharon noipunyer sohit Francer sarbosreshtho gitikobir koekti kobitar chamatkar anubad koriachen” (qtd. in Rabijibani, Vol II, 147-48)

[The peerless lyric-poet of Bengal with his creative brilliance and excellent craftsmanship has attempted a marvellous translation of some of the classic poems of the greatest lyric-poet of France].

He further opines that due to his sharp intellectual acumen in deciphering foreign languages, Rabindranath Tagore could provide an almost similar rendering of Hugo in his Bengali translations. In the next issue of ‘Desh’, (1970, 1327-31), however, French scholar and Tagore critic, Sourindra Mitra, contrary to Dr Chowdhury, expresses doubts about the depth of Rabindranath’s knowledge of French language. While critiquing Chowdhury’s article in “Alochona: Rabindranather Forashi Charcha”, he wonders whether Rabindranath, independently, translated the poems or not.

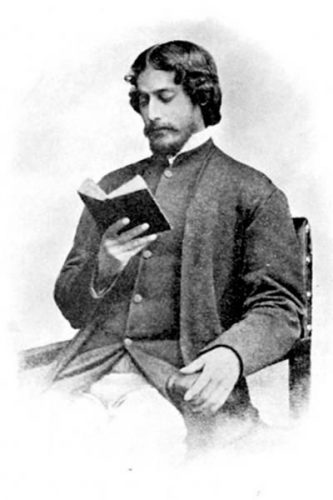

The translated poems impress Mitra as original creations to such an extent that he hesitated to give the credit to Rabindranath. This is because he feels that Rabindranath lacked a sound knowledge of the language. What Mitra perhaps fails to understand is Tagore’s main motivation behind translating poems from foreign languages. Factually speaking, during that time Tagore was involved in refining his dexterity of foreign languages, be it English or French. For instance, before going to England when he was staying at Ahmedabad for three months in 1878 with his brother Satyendranath, Rabindranath wanted to sharpen his spoken English skills. So he ventured into the difficult terrain of the English language by reading English history [History of English Literature by H.A. Taine] with the help of a dictionary. In his ‘Jiban Smiriti’, he confesses:

“Inregite nitantoi kancha chilam boliya somostodin dictionary loiya nanan inreji boi porite arambho koriya dilam. Balyokal hoite amar ekta obbhas chilo, sompurno bujhite na parileu tahate amar porar bandha ghotito na. Alposolo jaha bujhitam taha lohiya apon mone ekta kichu khara koriya amar besh ekrokom choliya jaito” (‘Rabindra Rachanabali’, Vol IX, 468)

[Due to the fact that I was weak in English I used to sharpen my skill by reading different English books with the help of a dictionary. Since childhood it was my habit to continue reading anything even though I could not understand everything completely. Whatever little I could make out, I was able to compose something in my mind]. Thus despite his limited understanding of the English language, he leant the English history, particularly the Roman conquest and the advent of Anglo Saxons. This endeavour led him to write essays and translations in native language. His essays – “Saxon Jati O Anglo Saxon Sahitya”, “Beatrice, Dante O tahar Kabya”, “Petrarch O Laura”, “Goethe O tar Pronoyinigon”, “Norman Jati O Anglo Norman Sahitya”– were published in the ‘Bharati’ magazine from mid June 1878 to mid February 1979 (“Pothe Probashe Kobir Lekhoni”, 44). He translated Anglo Saxon poems, for example, portions of Caedmon’s Genesis and Exodus and an abridged version of ‘Beowulf’ (‘Rabijibani’, Vol II, 12).

Interestingly enough, the English language facilitated him to read the translated poems of Petrarch and Dante. Thus not merely English history but through English language Rabindranath tried to get acquainted with European literature. Even though he was not an expert practitioner of the English language at that time, his earnest desire to translate English poems into his native language, was his distinctive method of penetrating through the boundaries of foreign language. This attempt is very similar to his attempts at translating French poems into Bengali at Chandernagore. The difference, however, lies in the fact that while at Ahmedabad he mostly helped himself in his venture to learn English, at Chandernagore he had the advantage of staying with a brother who was a French scholar. Translations of Hugo’s poems at Chandernagore was, therefore, initiated by his brother who fostered in him a love for French literature as well as a part of his creative agenda of an insightful journey into the arena of a foreign language, sharpening, at the same time, his skill of the same. Hence the translated products reflected an unquestionable literary value. As the western poems glide through eastern sensibilities, critics are dazed by their radiating qualities.

they knew each other very well and Nag translated Tagore’s ‘Balaka’ into French. Already a part of an informal network of Francophone artistic expressions, Rabindranath was further motivated to continue with cultivation of the French language through the translations from French into Bengali by Jyotirindranath done at Chandernagore.

With ‘Jyoti dada’ and ‘Notun Bouthan’, Rabindranath shifted to Moran Saheber Kuthibari shortly: “Kichudin por bari palte Moran Shaheber bungloye. Sheo Gangar dhare” (Sengupta 227) [After a little while they come to the Bungalow of Moran Sahib by the Ganges.]. Sometimes they arranged a picnic in the shades of Bokul tree, at times, the brothers roamed in the Ganges in their small boat. In Jiban Smriti, Rabindranath remembers Jyotirindranath playing violin in accompaniment of his songs and Akshay Babu, Jyotirindranath’s friend, visiting them (‘Rabindra Rachanabali’,Vol IX, 489). In ‘Gangatir’, from ‘Jiban Smriti’, Rabindranath further describes his time here:

“Amar Gangatirer sei sundor dinguli Gangar jole utsargo kora purnobikoshito padmafuler moto ekti ekti koria bhashia jaite lagilo” (‘Rabindra Rachanabali’,Vol IX, 488)

[My delightful days beside the Ganges went afloat like fully-bloomed lotus flowers drifting along].Like Barunjyeder Baganbari where amidst nature’s regal abundance Rabindranath was busy translating French poems into Bengali, in Moran Saheber Kuthibari too he was engaged in various creative compositions.

In contrast to the small, two storied structure of Barunjyeder Baganbari, the Palace of the Moran Saheb had a majestic interior:

“Seta rajbari bollei hoy. Rongin kacher janla deoa uchunichu ghor, marbel pathore bandha mejhe, dhape dhape gangar upor thekei siri utheche lamba baranday… .” (‘Rabindra Rachanabali’, Vol XIII, 733)

[It was almost like a royal Palace. The rooms, of varying heights, had coloured glass in their windows, the floors were of marble and steps led down from the long veranda to the very edge of the Ganges …].

The rooms in the house were at different levels, as if carelessly scattered here and there. The floor was made of marble, there was a long stone staircase coming upwards from the bathing-place by the riverside to the long and spacious veranda. The large and capacious drawing room had coloured decorative glass with pictures engraved on them. The pictures seemed to depict the myths and legends of a far away land and created an aura of mystery in which the poet loved to linger. Tagore started writing his first historical romance, ‘Bouthakuranir Haat’ (1883), in this house, and, according to Prasanta Kumar Pal, Tagore perhaps got a visual impression of the frame of this historical narrative from the two pictures which drew his mind out into the alleys of a forgotten past. Moreover, at the top-most level of this Palace of Moran Sahib, the poet’s mind found a room of his own to invoke the muse of imagination. It is this circular, dome-shaped room which became the altar of his prayer:

“Barir sarbocchotole charidik khola ekti gol ghar chilo. Seikhane amar kobita likhibar jayga koria loiachilam. Sekhane bosile ghono gacher mathaguli o khola akash chara ar kichu chokhe porito na…”(‘Rabindra Rachanabali’, Vol IX, 489)

[There was an airy room at the top most level of the house. There I made a place for myself to write poems. Nothing other than the leafy treetops and the expanse of the blue sky could be seen from there].

No wonder the immortal lines which he penned down – “Anonto e akasher kole/ tolomolo megher majhar/ eikhane bandhiachi ghor/ tor twore kobita amar” (‘Rabindra Rachanabali’, Vol IX, 489)

[‘Here, Wherein the lap of limitless space clouds/lie down to sleep,/ I have built my house for thee, O Poesy’]– succinctly confirm Chandernagore as the pristine abode where his poetic self flowered.

While resting in the lap of the Ganges, Tagore also composed some prose pieces quite distinct from his usual prose works: “Gangar dhare bosia Sandhya Sangeet chara kichu-kichu godyo O likhitam. Seo kono bandha lekha nohe—seo akrakom ja-khushi tai lekha…” (‘Rabindra Rachanabali’, Vol IX, 491)

[Coupled with Sandhya Sangeet I also wrote some prose by the Ganges. Those were not structured pieces, organized or framed—those were random delightful records].

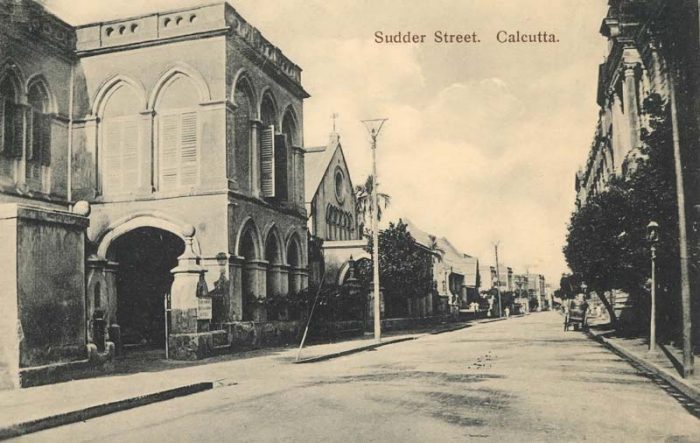

‘Bibidha Prasanga’, written during 1883, is a reservoir of precise and succinct passages numerous in number and diverse in thoughts. In chronicling the short essays, Pal in Rabijabani, allocates a specific course of time to these prose pieces; “Ei sankhipto prabandhaguli srabon 1288 theke suru kore kartik o agrahayon chara proti mas e koekti kore mudrito hoe boisakh 1289-sonkhyay sesh hoy arthat moran shaheb er bagane sutropat o sadar street er bashay abosthankaler kichudin porjonto ei rachonar dhara probahito hoe choleche”(‘Rabijibani’,Vol II, 155)

[These short prose pieces started coming out in pages from July 1288 (English 1881), appearing almost regularly, one or two each month, except for the period of late October to early December, culminating in the issue of April 1289 (English 1882), which means, it all began at Moran Shahib’s Bungalow and went on continuing till some days after they shifted to the house at Sadar Street].

Incidentally, Jyotirindranath and Kadambari moved to a house in Sudder Street, Calcutta, from Chandernagore. From the conversational tone of the essays and the short and pithy style, the interlocutor’s presence can be sensed and Tagore had later acknowledged the anonymous participant in the conversation is none other than his sister-in-law, Kadambari Devi.

Thus the Palace of the Moran Sahib acted as the necessary catalyst in the alchemic transformation of a young, sensitive soul into a creative artist par excellence. The garden house at Telenipara, sadly enough, could not withstand the ravages of time and Moran Saheber Kuthibari became a prey to growing urbanisation at Chandernagore. Tagore’s creative palace, pregnant with memories, was demolished, for areas adjacent to the Ganges were conducive to the establishment of Jute mills. As a great amount of water was needed in the processing of Jute, Moran Shahib’s Kuthi by the Ganges was bulldozed to make way for the Gondalpara Jute Mill. When Tagore came back to Chandernagore after many years of his stay at Moran Sahib’s, in 1935, his treasured Palace had disappeared. His lament, recorded in Harihar Sett’s ‘Rabindranath O Chandannagar’, is a pertinent observation of the inroads of industrialization. He sighs that his treasured house “louhodantur kabale kabalito” (“crushed and swallowed” by the “iron jaws of the Dundee Mills”).

Though the concrete structures no longer exist, yet the memories of those days recur directly in three of his short stories, ‘Apod’, ‘Adhyapok’ and ‘Pragati Sanghar’. While in the first two stories, written in 1894 and 1898 respectively, Tagore focuses primarily on the houses he stayed at Chandernagore, the last one, though episodically, is a critical evaluation of the French rule at Chandernagore. ‘Apod’ (Galpoguccho, 239-246), set in a garden- house by the Ganges in Chandernagore, is reminiscent of a young Tagore wandering and relaxing in the garden house of the Banerjees at Telenipara.

Moreover, the story begins on a stormy evening with the heated conversation between a couple, Sarat and Kiran, who have come to Chandernagore for a change of place – as Tagore’s family members often came for a change of air – prescribed by a doctor with a view to improve the health of Sarat’s ailing wife. Though Chandernagore is the locus standii, ‘Apod’ is basically an intricate story of relationships which has no traces either of French education or of colonial-native dialectics. However, the descriptions of the stormy night and of the natural ambience in the short story are partly autobiographical. ‘Adhyapok’ (Golpoguccho, 322-334), which preserves an episodic chunk of Chandernagore, has a direct reference to a garden house at ‘Farashdanga’ where the protagonist, Mahindrakumar, a student of Arts, comes with an ambition to write something marvellous. The vivid description of leisurely afternoons spent by the Ganges is partly autobiographical. The ‘bagan’ of ‘Adhyapok’ in ‘Farashdanga’ is an unmistakable reference to Barujyeder bagan. The third and fourth chapters contain glimpses of Moran Shaheber Kuthibari. One sultry afternoon rejuvenating his mind in fresh air, blowing from the Ganges, Mahindrakumar’s attention was drawn towards his neighbour, Kiranbala’s residence.

The description of Kiranbala’s house is that of Moran Sahib’s Bungalow. The author’s imagination overcasts a film of unfamiliarity around the house making it strangely intimate to the readers. Although in reality the two houses were not so near, in the short story, Kiranbala’s dwelling palace, resembling Moran Sahib’s Bungalow is the next neighbour of Mahindrakumar’s place of stay. Though set in Calcutta, ‘Pragati Sanghar’ (Rabindra Rachanabali, Vol XIV, pp 67-75], written almost at the end of his life, in between 11-21 June 1941, Calcutta has an episodic reference to Chandernagore. The protagonist, Niharranjan, is born and brought up at French ruled Chandernagore. His knowledge of the French language offers him a scope to address the visiting French scholars at his University: “Niharranjaner bari Chandannagare. Pratham boyesh e Forashi school e tar bidyasikkha, shekhane or bhashar dakhol niye khub khyati peyechilo, e-sob katha or kolkatar bondhumahal keu janto na…ki aschorjo, abhinandan jakhon porlo tar bhasar chhotay forashi pandit ebong tnar du-akjon anuchar aschorjo hoe gelen. Tnara bollen – erakom marjito bhasha Francer baire kakhono shoneni. Bollen, e cheletir uchit Paris e giye degree arjon koreasha”(73)[Niharranjan lives in Chandannagore. In the early years, he got his education in a French school, there he received acclaim and praise for acquiring the language so well, he never talked about these to his friends in Calcutta…to a great surprise, when the welcome note cascaded down gently, the splendour of his expression left the French scholar and his one or two companions speechless. They remarked – they had never come across such marvellous rendition of French beyond the boundaries of France and agreed in unison that the boy must come to Paris to get a degree]. The excerpted passage unearths the fissure, latent in the discourse of colonization, which is potentially prone to disruption. Niharranjan went to a French school at Chandernagore and learnt the language so devotedly, that his proficiency surprised a Professor from the Sorbonne. Nihar’s perfect acquisition of a foreign language and culture, subverts the authority of the colonizer over the native rather than reinforcing it, for the native, by imitation, has now created a third space of resistance and contest. Education, the colonizer’s tool for disseminating their culture and thereby manoeuvring the ideological genesis of the native, was a facile method of spreading Orientalism. But in this colonial encounter, the native intellectual surpasses the structure provided by the authority, creating a fracture in the colonial discourse, where predominance of plurality essentially erases the leverage of the ruler. Not only that, the French Professor and his acquaintances in the short story even suggest Nihar to come to Paris to get a degree. It shows the great leap the native has made. He is able to speak in the tongue of the master and his identity becomes the sign of deference and difference.

The quoted passage is also slightly revelatory in the attitude of the French towards the native. They seem to have a catholic mind to appreciate the other: “amra bideshi, jodi ba amader bhashay kimba boktritay kono truti hoy ta forashi adhyapak nischoi hashimukhe mene neben. Onra to ar Ingrej non, Ingrejra bideshider kach thekeo nijeder adobkaydar skhalan soite paren na, emon onder ahankar. Kintu forashider ta noy, barancha Jodi kichu asampura thake seta heshe graham korbe”(72). [The language is not our own, if there is any mistake in the way we want to convey our thoughts in the language, the French Professor would surely take that with a smile. They are not like the British, the British never tolerate a single flaw in the imitation of their etiquette, even from a person who is foreign to their language and culture, such is their pride. But the French are different, even if there is a sense of incompleteness in the expression, they would accept that ungrudgingly and wholeheartedly]. In this speech of an anonymous Bengali girl, who is Niharranjan’s classmate, Tagore points out the difference between the linguistic tolerance of the French and that of the British – while the British are always rigid, the French appear to have controlled parts of India, with a lighter hand. Though the story ultimately ends up to be a saga of unrequited selfless sacrifice, Tagore’s flashback strategy to include Chandernagore, thereby juxtaposing Niharranjan’s childhood knowledge of French reaping fruitful harvest in his postgraduate days at Calcutta University, speaks volumes of his nostalgia for Colonised Chandannagar; and French education, even as a short reference, is no meagre episode, for one unambiguously discerns the ambivalence inherent in the colonial discourse of early twentieth century Bengal. The three short stories, therefore, become insignia of Tagore’s deep sense of belonging to a place where he has returned time and again.

Interestingly enough, like his brother Jyotirindranath, a matured Rabindranath was attracted to French culture and heritage at Chandernagore. Rather going a step ahead of his ‘Jyoti dada’, Rabindranath was eager to know the effect of French education in colonial Chandernagore. While staying in the houseboat, ‘Padma’, near Ranighat in 1926, Rabindranath interacted with Mayor of Chandernagore, Sri Narayan Chandra Dey and the critical Francophile philanthropist, Harihar Sett. Harihar Sett in Rabindranath O Chandannagore recalls the incident: “[…]Chandannagore e Forashi bhasha sikkhar dhara o maan sombondhe obogoto hoibar jonnyo tini agroher sohit Narayanbabu ke bohu prosno koren” (Sett, 26) [In order to be aware of the standard of French education in Chandernagore, Rabindranath, keenly enough, threw volleys of questions at Narayan Chandra Dey]. In 1935, the poet anchored in the house boat, ‘Padma’, near the uncared-for shore of the house of Banerjees and rented Patalbari for sixty rupees a month :

“Chandannagar er e bariti anyanyo bari hote ektu alada rakomer. Anginar akdhar ghenshe por por eksari ghar. Dotola thik pothe giye misheche, nicher tola matir tole, joyare gangar jol chole ashe sekhane…” ( qtd. in Kabir Abash, 49) [This house in Chandannagar is a bit different from all other houses. The rooms are placed in a line, one after the other, at one side of the veranda. The upper storey has merged with the road whereas the ground floor is underground, in the time of rise the water of the river would come and fill the floor…]. The ground floor of the house was underground and water from the river would come with the flow making the rooms there unfitting to inhabit. One could use only the rooms upstairs. The river was so close to the house that one could hear the slashing sound of water touching the stones all day long. Patalbari is the only house well conserved at present.

Incidentally, Jyotirindranath and Kadambari moved to a house in Sudder Street, Calcutta, from Chandernagore. From the conversational tone of the essays and the short and pithy style, the interlocutor’s presence can be sensed and Tagore had later acknowledged the anonymous participant in the conversation is none other than his sister-in-law, Kadambari Devi.

If while staying at ‘Padma’ near Ranighat and at Patalbari Rabindranath expressed his desire to know about the level of French education at Chandernagore, during his short visits to the town, he interacted with French administrative personnel. For instance, in April 1927, Rabindranath was invited as a chief-guest at an inaugural programme arranged by ‘Prabartak Sangha’, a Hindu religious institution in Chandernagore founded by Motilal Ray in 1920. Tagore went to Krishna Bhabini Nari Siksha Mandir, a Girls’ school, established by Harihar Sett in 1926. On that day Tagore was also invited at a cordial tea-party in the French Residency especially organized by the French administrator in the honour of the poet. A charming aura was built up in the green lawn of the Residency by the Ganges. Eminent French scholar Sylvin Lévy, a former Professor at Visva Bharati and a devoted appreciator of Tagore, was also present there. Harihar Sett informs us: “Je sob Forashi administrator Chandannagore e ashiten, sadharonbhabe tanhara onekei Rabindraonuragi chilen”(38). [Generally speaking, most of the French administrators who came to Chandernagore were fond of Rabindranath]. Again, in an invitation to inaugurate the Bengali Literary Festival, 1937, Tagore expressed his desire to stay for a few days at Janhabi Nibas, which however, remained unfulfilled. Moreover, French administrator Monsieur Baron came to Chandannagar in 1940, long after Tagore’s last visit and in homage to Tagore Baron read his Gitanjali . Mrinal Ghosh in Rabismriti, as recounted in Sett’s Rabindranath O Chandannagore, recollects how Baron became so influenced by Tagore’s poetic style that he used to read Gitanjali every day before he joined office. Rabindranath and the French-ruled Chandernagore, small wonder, were tied up by an invisible bond.

Antara Mukherjee is an Assistant Professor of English at a college in Kolkata.

One Response

splendid