Kuzu Zangpo La/Greetings: To My Readers!

“Just another town, another train

Nothing lost and nothing gained

Guess I will spend my life in railway stations” – ABBA

Humming this melody, I boarded the Kanchan Kanya Express from Kolkata, determined to make the most of a long weekend. After an overnight journey manoeuvring through tea gardens, jungles, and tunnels, I reached Hasimara, crossed the border via Jaigaon, completed immigration formalities, paid the Sustainable Development Fees, and entered Bhutan through Phuentsholing. (Bhutan)

What a fascinating and inexpensive alternative to flights for an international trip! That said, I’d only recommend it to someone who, like me, occasionally craves a train journey with all its paraphernalia. For me, that craving is once in a blue moon. The craving to leave town, however, is strictly fortnightly. Ha ha ha.

Phuentsholing: First Steps into the Carbon-Negative World

Also Read: Reverie of a Pluviophile: Exploring Magical Meghalaya

Stepping into Phuentsholing felt like a breath of fresh oxygen. Barely five minutes earlier, I had been navigating the crowded, chaotic, and pungent market streets of Jaigaon. Within minutes, I found myself inside the world’s first carbon-negative country.

The difference was immediate. The roads were immaculate. There were no traffic signals. Instead, drivers instinctively stopped when pedestrians gathered at zebra crossings. Interestingly, traffic lights were once introduced, but the Bhutanese disliked them so much that they were eventually removed. Coming to happiness, I was told by my Guide that Bhutan has a system of Gross National Happiness, a system where governance is guided by indicators of citizen happiness rather than GDP alone.

Thimphu is not just Bhutan’s capital; it is the heart of its evolving political identity. Interestingly, Bhutan became a Constitutional Monarchy as recently as 2008 when the previous King abdicated his throne for his son and made several changes to the polity, such as the introduction of a multi-party system, universal adult suffrage, retirement of the king and so on.

Free education and medical services are major contributors to this happiness, largely funded by the Sustainable Development Fee collected from tourists. As theory slowly turned into lived reality around me, Bhutan’s approach began to feel less abstract and more deeply intentional.

Appropriately, my introduction to Bhutanese culture continued at the dining table. That afternoon, I tasted Ema Datshi—the country’s national dish of chilli and cheese served with rice. Simple, fiery, and comforting, it set the tone for what was to come.

Thimphu: Capital of the Land of Thunder Dragons

Leaving the border town behind, the journey to Thimphu unfolded through winding mountain roads and cascading hills. If one Bollywood line could capture that drive, it would be: “Yeh haseen wadiyan, yeh khula aasmaan…”

Thimphu has a new tourist attraction, inaugurated just a decade ago, Dordenma Buddha, a 51 metres tall golden Buddha made of copper and bronze on the slope of a hill. It has a serene temple beneath. That day, we were one of the first visitors at the giant complex, hence we had the temple to ourselves, where our Guide explained to us more about Buddhism.

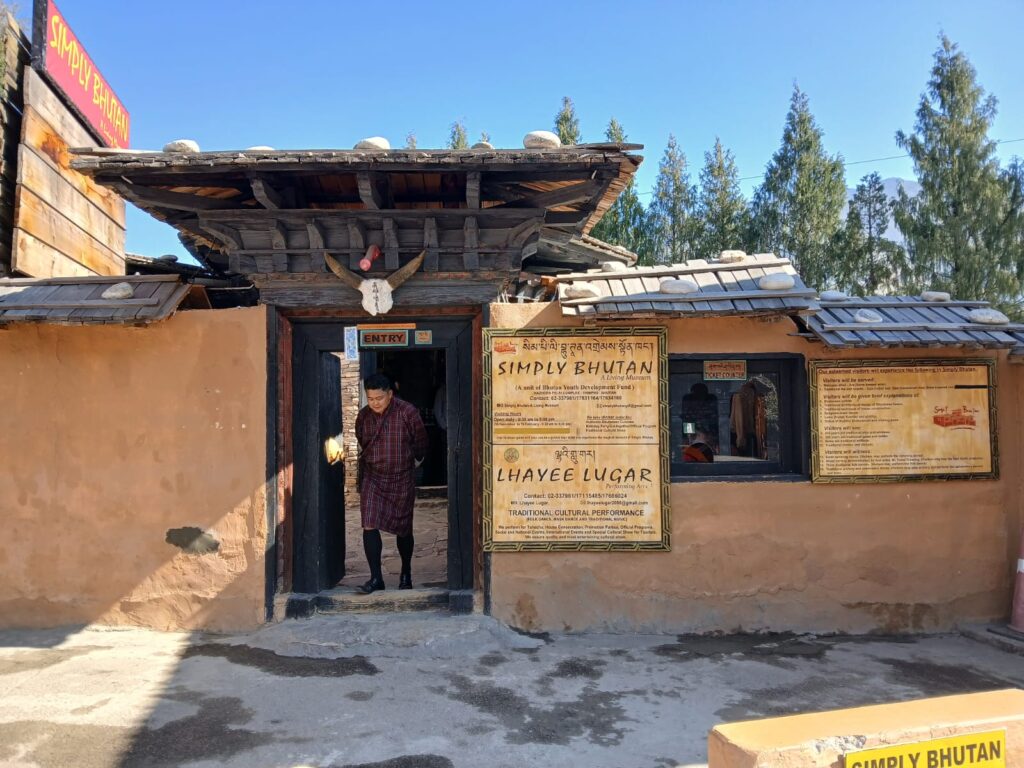

Next stop was Simply Bhutan: A Living Museum. The price of the entry ticket is Nu.1000 per person, which is too expensive for the experience it offers. Yet I justified it as a small contribution to an economy with limited revenue streams. Anyways, the museum staff welcomed us with a shot of welcome wheat-wine, named Ara – too good!

The museum walk-through covered the history of the royal family, the near-divine reverence citizens hold for their King, and cultural practices deeply woven into daily life. (The King’s picture is placed inside every temple, shop, restaurant, hotel and on souvenirs) I believe that their reverence to the King got consolidated when, during COVID, the borders were shut for 2.5 years and for an economy like Bhutan, which is highly dependent on tourism and imports, the King paid salaries to almost all of the citizens, cushioning them from the economic devastation experienced elsewhere.

As the museum unfolded, we explored traditional kitchens, watched folk dances originally performed by construction workers, learned about the symbolic worship of the phallus for fertility and protection from evil, and even joined dancers on the floor. Though not a tea drinker, I sampled Sujha—salt tea with yak butter—served with sweetened rice and puffed rice. An acquired taste, but memorable nonetheless. The museum ended with a demonstration of archery, Bhutan’s national sport. I tried my luck with a bamboo bow and arrow—my shot missed the target entirely and struck a board behind it. Humbling, but fun.

The final stop at Thimphu was the Takin Preservation Centre. Takins, Bhutan’s national animal, look like a curious hybrid: the head of a goat and the body of a furry cow. Lazy yet muscular, they grazed unbothered as I ran around the walkways trying to capture close-up shots. Legend credits their creation to the Tibetan saint Drukpa Kunley, the Divine Madman, who is said to have combined the skeletons of a cow and a goat and brought them to life. As with much of Bhutan, myth and reality coexist effortlessly, neither needing justification.

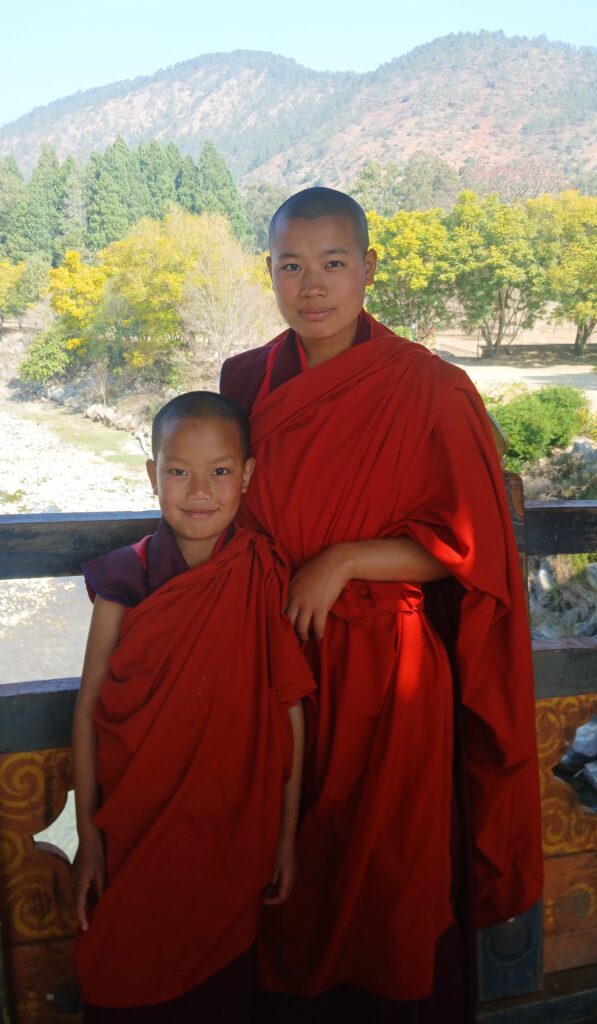

Thimphu is not just Bhutan’s capital; it is the heart of its evolving political identity. Interestingly, Bhutan became a Constitutional Monarchy as recently as 2008 when the previous King abdicated his throne for his son and made several changes to the polity, such as the introduction of a multi-party system, universal adult suffrage, retirement of the king and so on. Today, governance operates through a dual structure, balancing secular administration with religious authority, where the monastic body continues to play a central role, both united by the King.

Pristine Punakha

Left Thimphu for an hour drive to Dochula Pass, standing at nearly 9,000 feet, to witness 108 stupas and a breathtaking view of the Himalayan ranges forming Bhutan’s natural barrier with China. The biting cold made me hopeful for a January snowfall—but luck wasn’t on my side.

The drive from Dochula Pass to Punakha felt cinematic. I believe if Bhutan hadn’t followed its self-isolation policy, this region would’ve been a dream for cinematographers.

The Punakha Dzong, an erstwhile palace-fortress, stands majestically at the confluence of the male and female rivers. It is deeply sacred, housing the monastery where Bhutan’s first Dharma Raja attained nirvana. Local belief even credits Vishwakarma with assisting in its construction before heading to India.

The massive white walls, intricate woodwork in orange and yellow, and murals depicting Buddha’s life and Buddhist philosophy reflect Bhutan’s fierce commitment to preserving heritage. The Dzong still functions administratively alongside its monastic role. Nearby, a suspension bridge adds to the experience.

On the way back, we stopped at a local restaurant in Punakha overlooking the agricultural fields and the rust-coloured hills.I had Jasha Maru, a light chicken curry, and Zumzin, a local peach wine—easily one of the best wines I’ve tasted. Highly recommended.

To Be Continued…

Image Courtesy: Author

Aradhita Banerjee

Aradhita Banerjee is a final yearLLBstudent pursuing law from Symbiosis Law School, Pune. She has completed herunder graduationin Political ScienceHonors from St. Xavier's College, Kolkata.She hails from a musical Bengali family in Kolkata. When she is not delving into legal texts, she is exploring new destinations, reading new books, and appreciating cinema andfinearts.