Uma Dasgupta is a renowned scholar and biographer of Rabindranath Tagore. In this essay she discusses at length the social and economic reforms undertaken and implemented by the Tagore family in the tribal villages around Santiniketan. Originally written as a paper to be read out at a seminar in the University of Illinois, this essay will be published in four parts on Space.ink.

Born in late nineteenth century Bengal, Tagore lived in ambivalent times. On the one hand there was the presence of British imperialism, on the other a strong feeling for the Indian past. The unequal relationship of master and subject left both sides without respect for the other as human beings. Since the Indian Mutiny of 1857 there was a tense atmosphere of rising nationalism in India. In the eighty years of Tagore’s life, 1861 to 1941, the British-Indian encounter sometimes came close to a clash of civilizations — and had to be resolved piecemeal by adjustments at various levels of Indian life. There were oppositions between the East and the West, between tradition and modernity, between the past and the present.

Tagore chose the difficult middle path of neither radical modernism nor proud traditionalism. He did that in the face of scorn and threats from his contemporaries in both camps, westernisers and traditionalists. His was an early voice for a modern Indian consciousness in which the Indian is reconciled with the Western. His faith in the creative nationalism of India grew and developed into the larger ideal of a cultural cooperation among the peoples of the East and West, which he chose to call the ideal of Visva-Bharati. There were two things that drew him to the world. One was his determination to break out of the isolation imposed as much by the Indian past as by colonial rule. The other was in his strong interest in modern science which was centred in the West.

Indeed, he valued the scientific approach as much in humanistic research as in agricultural and rural reform. It was part of his life’s commitment to redeem the neglected Indian village by creating a new education built upon cooperation between the city and the village by which he meant cooperation between scientific and traditional knowledge. This experiment at reforming education began as a school in 1901 at Santiniketan, in the heart of rural Bengal, then extended to become an international university called Visva-Bharati in 1921, along with a centre for rural reconstruction named Sriniketan.

Here is what he wrote early on about science when calling for its application in the cause of humanity:

Science has given man immense power … This latest manifestation of man’s power must be brought into the heart of the villages. It is because we have omitted to do so that our water-courses and pools have run dry; malaria and disease, want and sin and crime stalk the land; a cowardly resignation overwhelms us. Whichever way we turn, there is the picture of defeat, of the penury due to the depression of defeat. Everywhere our countrymen are crying, ‘We have failed.’ From our dried-up hollows, our fruitless fields, our never-ceasing funeral pyres, rises the wail, ‘We have failed; we have failed; we own defeat!’

In conclusion Tagore wrote,

If we can but gain the science that gives power to this age, we may yet win, we may yet live.

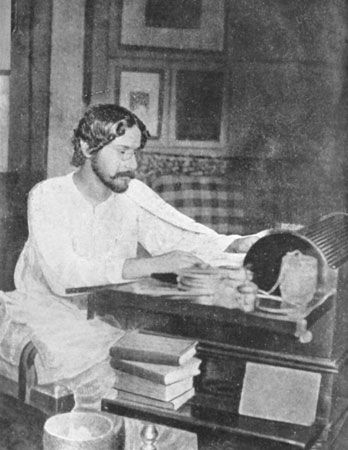

His first opportunity for some action came when he was sent by his father to take charge of his family’s agricultural estates in Eastern Bengal in the 1890s. We know from his letters published in Glimpses of Bengal that the turning point in his love and compassion for human beings, and for his free thinking and unconventional religious beliefs, came out of his early contacts with the peasants of Bengal. The daily business of looking after the estates enabled him to see at first hand how the majority of his countrymen lived. While suffering abject poverty those peasants still firmly believed that God would protect them in their miseries just as God had decided their fate at birth.

Born into aristocracy himself Tagore felt humbled by this experience. Their utter helplessness stirred the depths of humanity in him. He became determined to raise them from that state of ignorance and moral dependence. He also wanted to bring an awareness about their state of being into the education of the elite.

In 1893 he wrote,

The soil in which we are born is the soil of our village, the mother earth in whose lap we receive our nourishment from day to day. Our educated elite, abstracted from this primal basis, wander about in the high heaven of ideas like aimless clouds far removed from this our home. If this cloud does not dissolve into a shower of loving service, man’s relation with mother-earth will never become truly meaningful. If all our ethereal ideas float about in vaporous inanity, the seed time of the new age will have come in vain.

Tagore had two objectives in his ideas of rural reform: one was to educate the villager in self-reliance, the other was to bring back ‘life in its completeness’ to the villages with music and readings from the epics as in the past. The work was initiated around 1905 when he withdrew his participation in the nationalist Swadeshi Movement after turning thoroughly disappointed by its communal politics and what he described as ‘the anarchy of emptiness’. His was a solitary voice reiterating his faith in a constructive programme.

He wrote,

After a certain point is reached, I find myself obliged to separate myself from my own people, with whom I have been working, and my soul cries out: the complete man must never be sacrificed to the patriotic man, or even to the merely moral man. To me humanity is rich and large and many-sided.

He decided to fall back on his own estates for a constructive programme at the grass roots by working directly with the Hindu and Muslim tenants living on his estates. He had to proceed gradually as his resources were limited. A Welfare Fund and Welfare Society called the Hitabadi Sabha was established in the estates at Potisar in 1905 to organise primary education and public works and also to find a protective mechanism to save the cultivators from their ruinous indebtedness to the money-lenders. In his essay called ‘Swadeshi Samaj’(National Society), written in 1904 he outlined a comprehensive programme for the reorganisation of rural Bengal on the basis of self-help and the revival of indigenous industries.

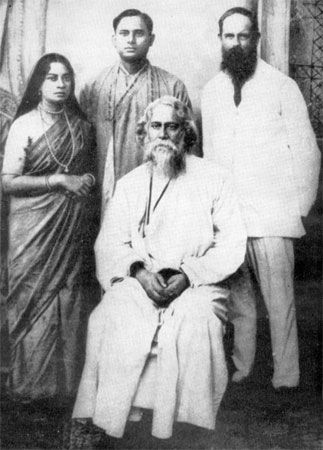

In 1906, as part of this larger scheme of things he sent Rathi and Santosh to study scientific agriculture and in the following year his son-in-law Nagendranath Ganguli too to the University of Illinois. With the return of all three of them from Urbana the rural work was gradually extended from the East Bengal estates to the surroundings of the Santiniketan school. He bought land for an experimental farm in 1912 in Santiniketan’s neighbourhood.

Given the problems of over three hundred million rural people Tagore hoped at least to touch the hearts of his village neighbours at Santiniketan. It was these ideas that led him a few years later to establish Sriniketan and develop it for a dedicated programme in scientific farming and rural reconstruction. He hoped that success with restoring ‘life in its completeness’ even in a single village might serve as an ideal for the whole country.

During this period when he was so completely absorbed by the stark reality of the life of the common people his poetry expressed a certain mysticism which was later to become an essential part of his writing. This mysticism did not belong to a creed or a school of philosophy. It expressed itself in several of his poems in the period 1894 to 1900. One such poem called Jiban-debata or ‘Lord of my life’ expressed the idea of a personal God and became a key concept in analysing his mysticism but has eluded all attempts by critics to give it any concrete context. Tagore himself called it a ‘baffling mystery’ and defined it differently for different moods. To him it felt like a power greater than himself which was using him as an instrument for an unknown purpose.

In a letter of 1894 he wrote,

I am overwhelmed by this awareness of the baffling mystery within me which I can neither understand nor control. I know not where it will take me or I it, I know not what I can do nor cannot do. I cannot see, nor am I consulted about, what surges up in my heart, what flows in my veins, what stirs in my brain, and yet I move about and keep up the pretence that I am the master of my thoughts and deeds.

He resolved the mystery for himself when he was convinced that the divine was to be found in humanity and that humanity was forever in search of the divine. In a letter of 1927 he described his concept of Jiban-debata as,

the limited aspect of divinity which has its unique place in the individual life, in contrast to that which belongs to the universe.

A historian and Tagore biographer who is a former professor of The Indian Statistical Institute. Friendships of 'Largeness and Freedom', Andrews, Tagore and Gandhi: An Epistolary Account, 1912-1940, Rabindranath Tagore an Illustrated life, Santiniketan and Sriniketan are some of her celebrated works. She is a noted Tagore scholar and biographer.