Arupa Patangia Kalita is a familiar name among readers of Assamese literature. Her works, dealing largely with women’s issues, are contemporary. Author and translator, Mitra Phukan’s translation of Kalita’s short stories collated in The Owl, the River and the Valley, published recently by Penguin Books is a timeless collection of women’s agonies and their relentless zeal in pursuing definite lives despite the patriarchy that shackles them. These stories, embedded deeply in the Assamese cultural ethos are difficult to make sense of when uprooted from their linguistic roots. translating

Yet, Mitra Phukan’s translation overpowers every linguistic hurdle and becomes a seamless conglomeration of tales on shared experientiality. I caught up with the translator to understand her process of translation. In this interview, Phukan talks extensively about the politics of translation, the need to decolonise the enterprise and what the future might hold for Assamese literature in English translation. The discussion is shared below.

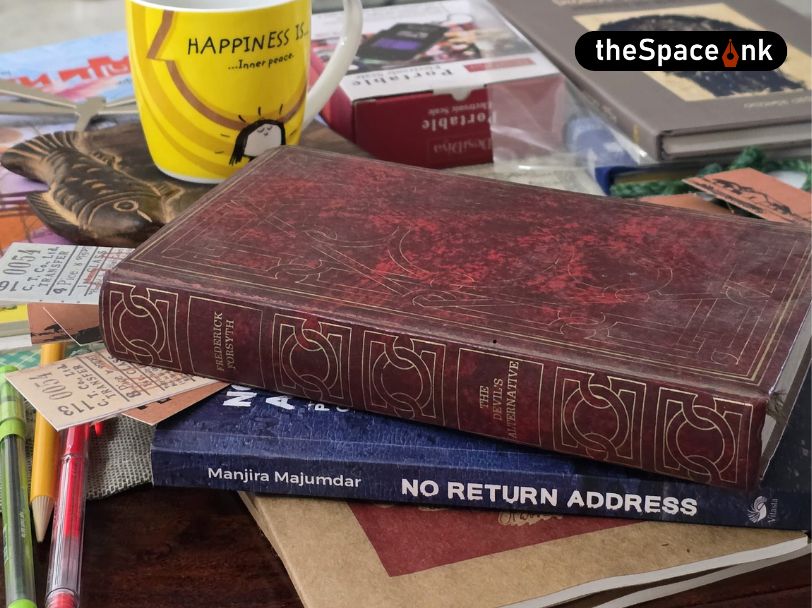

The Owl, the River and the Valley

AN: Congratulations. The stories collated in the anthology, The Owl, the River and the Valley are very unique but also tied together with the element of experientiality, especially of women. What was your process of choosing these twelve stories?

MP: Thank you, Anannya.

About the process of choosing the stories, I am familiar with Arupa’s work, as she is with mine. I am aware that she writes mostly about subaltern women, so I knew these stories would have this kind of protagonist. I was also clear that I wanted contemporary stories, and stories also that have not been translated into English or other languages yet. Arupa is a prolific writer, so it was not difficult to find stories that fit these criteria, while being also very engaging and often moving. We discussed these before I started to work on the stories.

Actually, Arupa had requested me to translate “Rajmao” for an event she was attending. It was after doing this, that the idea of a collection took root in both of us. Simultaneously!

Also Read: Deuta, Will You Buy Me a Doll?

AN: On reading the stories, one notices that parts of your translation have phonemic correlation with the way words are sounded in Assamese. What made you utilise such a method? Was it intentional or purely coincidental?

MP: No no, not coincidental at all.

Over the years, I have come to prefer spelling Assamese words phonetically, if they are used in the work. It’s political. The logic is …I am translating from Assamese to English. Why bring in the spelling of another language, even if it is more familiar to readers in the rest of India? This, to me, denotes a kind of mental laziness, even, in a way, a kind of slavishness.

For instance, the phrase “Ponso Pandob”, which, many Indians would be familiar with as “Pancha Pandav”. But we pronounce it “Ponso Pandob”, and that is the spelling I have used. Also, because it is used ironically, a little bit of explanation is incorporated into the storytelling itself. In any case, many readers in English would not be familiar with the term “Pancha Pandav.”

Some other things I am militant about are the use of footnotes and endnotes. I feel that as a translator, I should be able to bring clarity to my translation without these. I put in phrases, sometimes small sentences that make the meaning clear while not interrupting the flow of the story. I dislike italics too, because I feel it connotes some kind of linguistic hierarchy. But for this book, Penguin has some in house rules …italics for the first time a word that they felt needed it, then non italics for later uses.

Also, for instance, I use the spelling “ricksha” rather than “rickshaw”. This is because I feel the latter has colonial connotations, and in any case, it’s pronounced “ricksha” in Assamese.

The thing is, even in my original works, I use these spellings. Also, I never put footnotes in my own works, preferring unobtrusive descriptions in the text itself. I feel in my own works, too, I am translating… not the language of course, but the cultural connotations.

The first thing I do when I undertake a work of translation is set aside my own style consciously. It’s not difficult because the style of the text to be translated takes over.

AN: Do you think the Assamese syntax poses constraints in translating the same into English? How can any translator keep up the aesthetics of the two languages intact?

MP: Oh yes of course. I would say both languages are as different as possible syntactically. In my experience, the syntax of the source language tends to creep in slyly into the final text. To catch these bloopers, one needs multiple revisions, each time with a fresh mind. I am also grateful to sharp-eyed editors, because these things tend to pass by sometimes.

While revising and editing, I am also particular about the “flow” of the language in English, my target language. I like to have a rhythm, which syntactical errors will definitely interrupt.

AN: Can you give us an idea of how you translate colloquial phrases or untranslatable expressions in English? How far, do you think, a translator can or should maintain the equivalence in both languages while doing so?

MP: This is very difficult. But I feel that the worst thing would be to ignore the cultural connotations in the phrases in the two languages. Not all languages have similar phrases obviously. Sometimes I invent phrases, in the same pithy manner of an idiom, in order to convey the same kind of “feel” in the target language. I enjoy doing this…and this is where the creativity of a translator comes in.

Another problem I have faced is when the story itself uses multiple languages. The narrative in Assamese, but then some conversations in say Hindi, Bangla and/or Urdu. To keep reiterating …he said in Assamese, she said in English doesn’t work very well. I’m still trying to solve this problem!

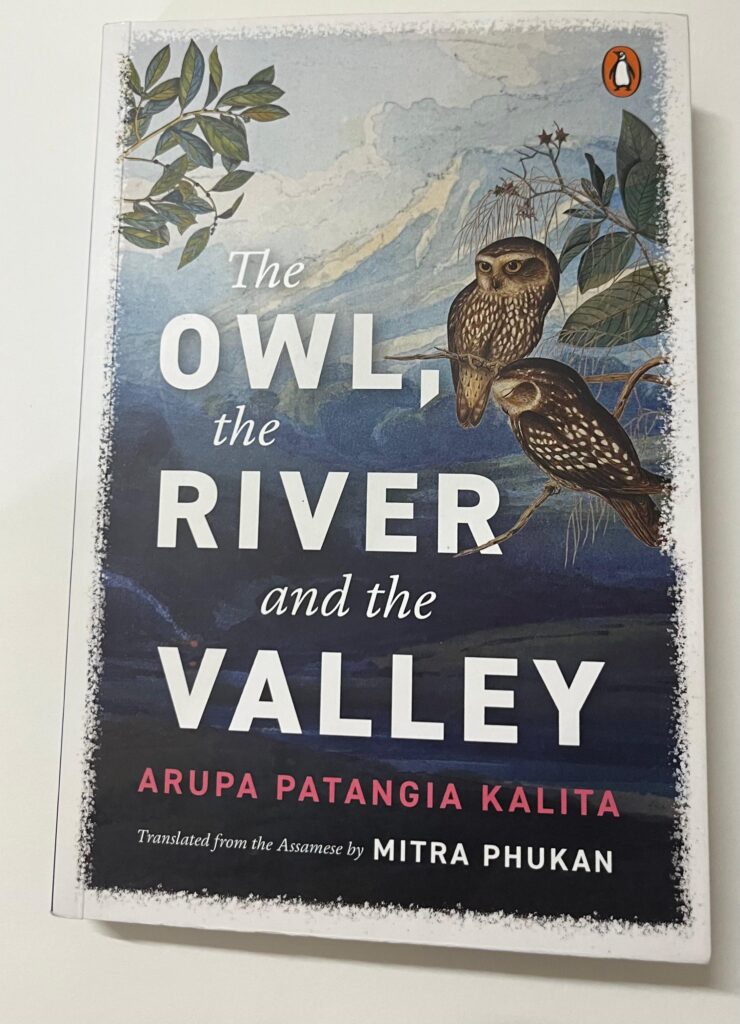

Renowned Translator, Mitra Phukan

AN: While translating the stories in this collection, which story proved to be the most challenging and why? How did you navigate through your challenges?

MP: The last story, “The Water is with Child” was very difficult, as I knew it would be from a first reading of it. It is very allusive, filled with all kinds of references, some overt, but often only indicated. I did not want to “explain” all of this to a non-Assamese readership, and yet, some level of subtle “explanation” would have to be put in. This again called for creativity! translating

The story is also very atmospheric, while being at the same time dramatic. I was careful to keep this balance. It is dripping with piety, because it is set in the portion of the Brahmaputra that flows between the river island of Majuli, with its xattras and modes of worship, and the town of Jorhat. translating

AN: You have worked with several Assamese authors and everyone writes differently. You are also an author yourself. How does your own creativity affect your translation? Do you believe that your approach changes with changing authors?

MP: The first thing I do when I undertake a work of translation is set aside my own style consciously. It’s not difficult because the style of the text to be translated takes over. Yes, all the authors I have translated have very different styles. Harekrishna Deka’s fictions have a crisp narrative, though many of his stories are deeply philosophical and allegorical. Arupa Kalita’s style has a lot of orality …repetitions, rhetorical questions …And Birendra Kumar Bhattacharyya’s style is suffused with a deep humanism. translating

I try to bring in as much of the aroma of their language, their style into the translation to get a flavour of their work. I enjoy the process of translating not just the stories, but also the style, as much as possible.

Perhaps the first translator to do excellent work is Dhirendra Nath Bezboruah, whose translations used to appear regularly in “The Illustrated Weekly of India” when it was widely read, with Khushwant Singh as the editor.

AN: Do you think it helps if a translator is also a writer in the target language? How?

MP: For me, it has, though it’s not a given that it should. Since we are working in the target language for our own efforts, our familiarity with it is deep. But this need not be the case always. There are some excellent translators worldwide who do translations only, and they are equally adept at both languages. translating

AN: What advice would you give to someone who is just starting out as a translator of Assamese literature?

MP: I don’t like to give advice! We all have to find our own path, our own ways of doing things.

But since you ask:

It’s important to remember the demands of the target language, while being true to the source language as well. Ultimately, the work will be read in the target language. Also, one must resist the urge to skip portions of the text to be translated. It’s there for a reason, and one must respect that. translating

AN: Why, do you think, there is such a huge lacuna of translation in Assamese to English literature as compared to the repertoire of translated literature found in English of other Indian languages like Tamil, Malayalam, Bangla or even Urdu? How can this issue be resolved?

MP: Several reasons. Though our stories are world class, our population is small. So, in numerical terms, the number of good writers is tiny compared to those linguistic groups that have large populations. translating

Also, translation was not taken seriously till recently. Authors got their works translated by people who often did it mechanically. Sometimes the bloopers were embarrassing, and in any case there was no soul in the translations. Perhaps the first translator to do excellent work is Dhirendra Nath Bezboruah, whose translations used to appear regularly in “The Illustrated Weekly of India” when it was widely read, with Khushwant Singh as the editor.

Translation requires a specific skillset. Being a creative writer, or an academic, for instance, may not be enough. The encouraging thing is that many great translators are now coming up. translating

In this context, the book The Greatest Assamese Stories Ever Told (published by Aleph) is taking twenty-five classic stories and authors out into the world. It was my privilege to have partly translated and edited the work, and it is gratifying to see its impact.

AN: Other than the authors you have already translated, whose work would you love to translate in the future? Why?

MP: I am a slow translator. I do feel good about being able to translate these wonderful works, but I think I’ll give it a break now, and concentrate on my own work, waiting for some time in the wings!

A dream I have had for a while is to translate some Borgeets, the sacred songs of the Xattriya tradition, into English. But that is a very daunting task. Let’s see …maybe someday down the line. Not all of them, just a few. And needless to say, I shall give this my all…my heart, mind and soul! translating

Image Courtesy: Author

Translating

Anannya Nath holds a Master of Arts in Literature from Tezpur University. She is currently working as an Assistant Professor of English in Biswanath, Assam. Her short stories, poems and translations have appeared or is forthcoming in The Chakkar, The Pinecone Review, Yearbook of Indian Poetry in English (2023), Muse India, Monograph, Rhodora, Gulmohur Quarterly, etc. She was longlisted for the Mozhi Prize, 2023 for translating Lakshminath Bezbaroah’s Assamese short story, “Madhoimaloti” into English and shortlisted for The BWW Short Story Award (The R K Anand Prize), 2024. Some of her published works can be found here: https://linktr.ee/anannyanath