Murder of the Manager

Edward Richard Henry (1850-1931) in his ‘Classification and Uses of Finger Prints’ (4th edn., 1913) gives an account of the murder case of 1898 that proved to be the first in the British Empire and the English-speaking world where the evidence of fingerprint was used for conviction.

The manager of a tea plantation in the Jalpaiguri district of Bengal had been found dead in bed. His throat was slit, his room ransacked and several hundred rupees were stolen. The primary suspects were a coolie from the plantation, the cook on whose clothes blood stains were found, relatives of a local woman with whom the victim had an illicit affair and a band of Kabuliwallahs (deemed by the British to be potentially criminal) then active in the area.

From the victim’s papers a calendar book (a Bengali panjika) was found. On its cover a faint brown fingerprint was discovered. This print matched exactly with the right thumb impression of one Kangali Charan. Kangali was an ex-servant whom the victim had caused to be imprisoned for theft. He had been released a few weeks before the crime.

He was arrested from Birbhum and brought to Calcutta (now Kolkata) and his thumb impression was re-examined. He was tried for murder and theft but convicted only for theft since he had not been witnessed committing the murder. This verdict was later upheld by the Supreme Court.

The Finger Print Bureau

Henry was at that time Inspector-General of Police, Lower Provinces of Bengal under the British administration. In 1897, a two-member committee comprising the Surveyor-General of India and the Principal of Presidency College, Calcutta looked into the efficacy of the fingerprint classification system. They recommended it to the British government of India. This system of classification now bears Henry’s name. Under Henry’s direction, the first “Finger Print Bureau” in the world was officially established on 12 June 1897 in Calcutta at the Writers’ Building. The bureau was locally popular as the tipshala. The repository of the prisoners’ fingerprints in Calcutta played a vital role in the identification of Kangali Charan as the murderer of the plantation-manager.

In 1900 Henry was sent to South Africa, where he introduced the fingerprint system among other reforms. The following year Henry was made the head of the Criminal Investigation Department at Scotland Yard and in 1903 the Commissioner of the London Metropolitan Police. In July 1901 he established the Metropolitan Police Fingerprint Bureau, following the principles tried and tested in Calcutta.

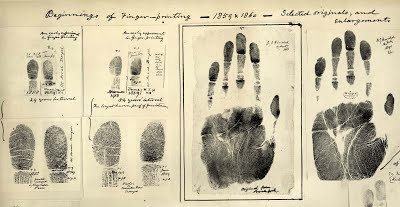

William James Herschel and his fingerprint index

The Bengal link with fingerprint collection and classification goes further back in history. William James Herschel (1833 –1917), a British administrator who was stationed in Bengal, may be credited as the first European to use fingerprints extensively for the official purpose of individuation and identification. In July 1858, at the beginning of a road-building project in Jangipur (now in Murshidabad district of West Bengal), Herschel almost serendipitously made a supplier named Rajyadhar Konai sign the contract with the impression of his right hand.

This was the beginning of Herschel’s life-long fascination with fingerprints. He did not have the scientific gift of his forebears. His grandfather William discovered the planet Uranus and his father John was a polymath who contributed to the invention of photography and also the construction of Babbage’s proto-computer. But W. J. Herschel had a curious and tenacious mind. He collected fingerprints of friends and associates, including top civil servants, police officers and also the Maharaja of Nadia. Often he requested for repeat prints years later. Many of these were published in his monograph ‘The Origin of Finger-printing’ (1916). He understood that every individual’s fingerprint was unique and that it was practically unalterable.

The ‘Samsad Bangali Charitabhidhan’ mentions a civil servant called Ramgati Bandyopadhyay who worked with Herschel in Hooghly for the collection of fingerprints, but Herschel does not mention him.

When he was the Magistrate and Collector at Hooghly, Herschel started keeping a register of fingerprints for the disbursement of government pensions and signing of deeds under his jurisdiction. Herschel also started recording fingerprints of every prisoner to weed out the possibility of a convict hiring a substitute to serve out a term on his behalf or that of a prisoner faking death with the help of a purchased corpse.

The ‘Samsad Bangali Charitabhidhan’ mentions a civil servant called Ramgati Bandyopadhyay who worked with Herschel in Hooghly for the collection of fingerprints, but Herschel does not mention him. On the eve of his retirement, Herschel requested the Registrar-General and Inspector of Jails to give his method a try, but was ignored. His method was even scrapped on his return to England in 1878.

Faulds and Galton

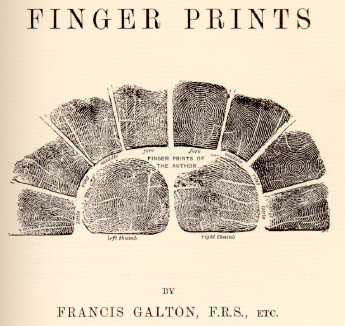

Meanwhile, Henry Faulds (1843 –1930), a Scottish doctor working in Japan, wrote a letter to the ‘Nature’, “On the Skin-Furrows of the Hand,” which was published on 28 October, 1880. He summarized the observations he had made on the topic in Japan and suggested the utility of fingerprints for “medico-legal investigations” and “scientific identification of criminals.” Herschel wrote a letter to the same magazine, which was published in the 25 November 1880 issue, claiming politely his precedence in the field. He declared that he had maintained “sign-manuals” for “more than twenty years” and used them for the practical purpose of identifying pensioners, signatories of deeds and also prisoners.

Faulds sought to collaborate with Charles Darwin (1809-82) for his research on fingerprints, but Darwin passed Faulds’s observations on to his cousin Francis Galton (1822-1911), a prolific and polymathic scientist. Galton was largely responsible for giving scientific credibility to fingerprints as an aid to criminal investigation. E. R. Henry sought Galton’s expert opinion before introducing the fingerprint system in Bengal.

Galton did not acknowledge Faulds when he started working on the subject, but he received with gratitude information from Herschel. In his monograph Herschel states that the widespread manner of signing among illiterate people in India is to wet the tip of one finger with ink and touch the paper lightly with it. He adds that such a sign is called a tep-sai (in Bengali), tep meaning “pressure by touch or grip” and sai meaning “token.” Galton in his book ‘Finger Prints’ (1892) uses the term ‘tipsahi’, but he agrees with Herschel that it represents a ritual and is not meant to identify the signatory.

Haque and Bose

Several recent scholars, both South Asian and Anglophone, have argued that the “Henry Fingerprint Classification System” was actually devised by two Bengali Sub-Inspectors‒ Qazi Azizul Haque (c. 1872-1935) and Hem Chandra Bose (1867-1949). Here one recalls the analogous case of Radhanath Sikdar (1813-70) and the naming of Mount Everest. Haque was born in an obscure village in Khulna, now in Bangladesh and proved to be a brilliant student of Mathematics and the sciences at Presidency College. He devised a formula for slotting fingerprint cards into 1024 pigeonholes of a cabinet, arranged according to fingerprint patterns. Such a cabinet could easily house about 100,000 prints.

Several recent scholars, both South Asian and Anglophone, have argued that the “Henry Fingerprint Classification System” was actually devised by two Bengali Sub-Inspectors‒ Qazi Azizul Haque (c. 1872-1935) and Hem Chandra Bose (1867-1949).

Bose was born in a small village now in Chuadanga district of Bangladesh. He studied Mathematics at Sanskrit College, Calcutta. Bose had already proved his mettle as an investigating officer before being posted at the police headquarters in Calcutta. Besides working with Haque on the fingerprint classification method, Bose later invented a single-digit telegraphic code for fingerprints. He explained the code in his monograph Hints on Finger-Prints with a Telegraphic Code for Finger Impressions (1916). His method came to be used in Bengal from 1917.

E. R. Henry rose to the stature of an English national hero. However, he scarcely had the mathematical aptitude for pulling off the intricate fingerprint classification. The story propagated by Henry that he had hit upon the idea in a moment of inspiration while travelling by train and scrawled it on his cuff, is hardly convincing. Henry never acknowledged Haque and Bose in his monograph or in his representations before committees. Much later, Henry recommended them for state titles and a monetary reward, while reserving for himself the principal credit for inventing the “Henry System.” Even in the new millennium, state redressal is slow to come. Reassuringly, netizens have been quite active to give Haque and Bose their due.

Bibliography:

- Classification and Uses of Finger Prints (4th edn., 1913), Edward Richard Henry

- Hints on Finger-Prints with a Telegraphic Code for Finger Impressions (1916), Hem Chandra Bose

- Nature

*Image courtesy: Amazon, forensicscience

Abhishek Sarkar teaches at the Department of English, Jadavpur University. He specializes in the literature and cultures of early modern England and colonial Bengal.