(McLeod Rail)

On a humid morning in the mid-19th century, when India saw its first steam engine hiss to life in Bombay, Karl Marx watched the moment from afar and wrote something striking: “The railway system will therefore become truly the forerunner of modern industry in India.”

He wasn’t wrong. What began as a colonial tool slowly became a lifeline—connecting villages, stirring economies, and sewing together cultures that had never met. But the grand rail lines we know today weren’t the only ones shaping India’s story. Some lines were tiny, almost playful. Some ran through courtyards, halting because a grandmother waved her hand. Some were built not by the government, but by private dreams.

Also Read: Stockholm in Fall: An Autumn Sonata

And in Bengal, four such dreamlike railways were built by a company that most people today have forgotten—McLeod’s Light Railways (MLR).

Where the Story Begins

Let’s travel back to a Bengal where coal ruled industry, and horse-drawn carts groaned along muddy roads. Visionaries like Prince Dwarakanath Tagore, Mutty Lal Seal, and Ram Comul Sen pushed the East India Company to introduce a railway system—mainly to carry coal from the mines of Burdwan to the Calcutta port. When the East Indian Railway Company began operating in 1854, they probably didn’t realise how quickly the idea would grow.

In the next fifty years, British capitalists discovered something beautiful: the railway business was profitable. Land was free. Labour was cheap. And the Government of India was more than happy to let private companies build tracks.

This was when McLeod & Company, a subsidiary of the London-based McLeod Russel, decided to step onto the stage.

McLeod’s Four Little Lifelines

Between 1913 and 1920, McLeod built four narrow-gauge railways in Bengal:

- Burdwan–Katwa Railway (BKR)

- Bankura–Damodar Railway (BDR)

- Ahmedpur–Katwa Railway (AKR)

- Kalighat–Falta Railway (KFR) (McLeod Rail)

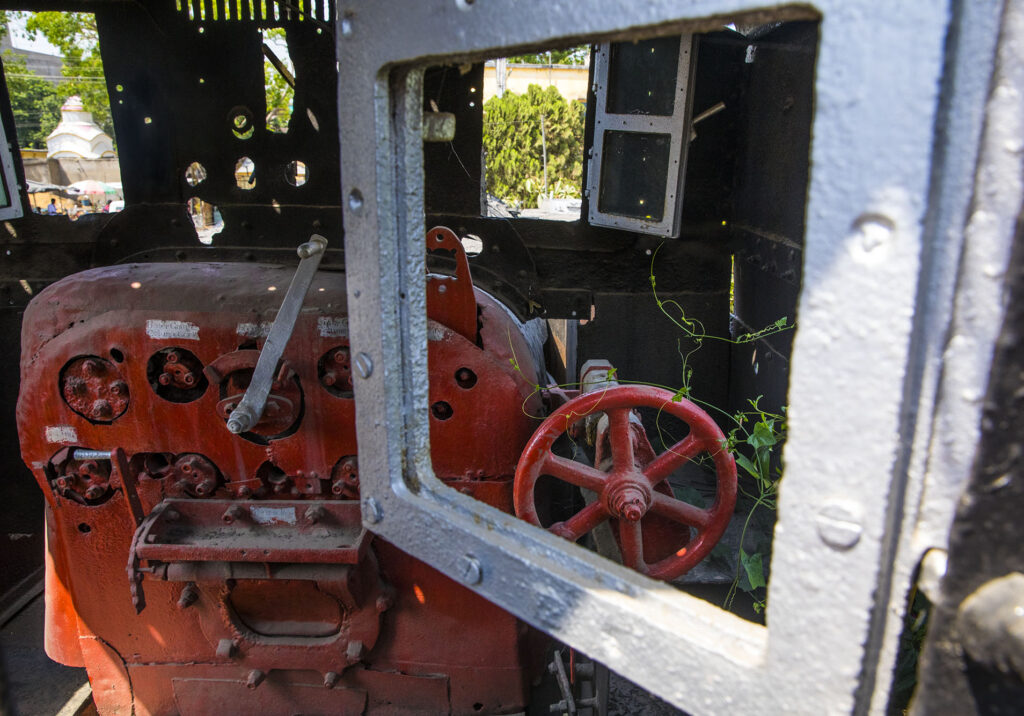

These lines were tiny compared to modern standards. They ran on flat-footed rails, rested on durable Sal wood sleepers, and used moorum as ballast. They were unfenced, uncomplicated, and unbelievably charming.

Government contracts allowed McLeod to build freely, but with two conditions:

- Fares had to follow government rules

- The state could take over the railway any time with 12 months’ notice.

Little did McLeod know that both things would eventually happen.

The Four Lines, Four Stories

1. Burdwan–Katwa Railway (BKR) – 1915

Registered in 1913, opened in 1915, this 54-km line touched sixteen stations. It felt like a humble ribbon tying together Burdwan’s bustle with Katwa’s quiet charm.

Trains here did not rush. They wandered. (McLeod Rail)

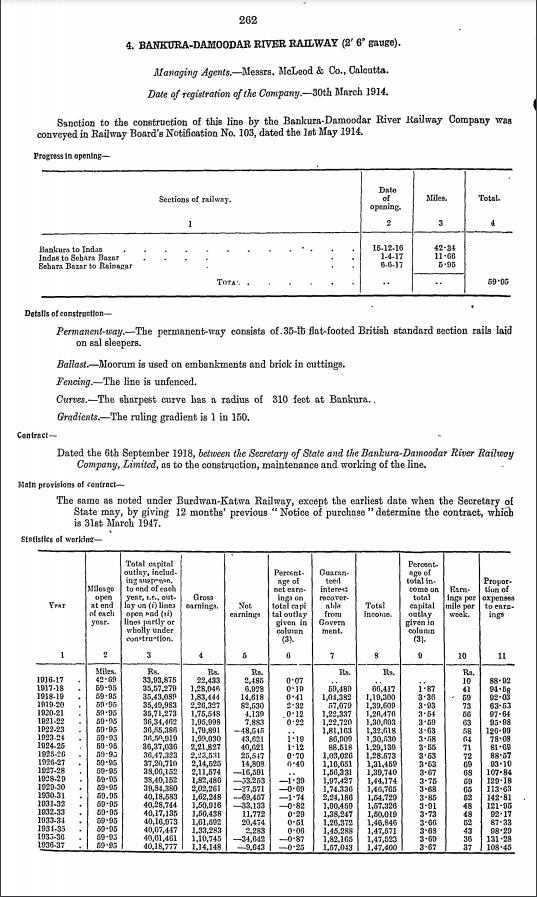

2. Bankura–Damodar Railway (BDR) – 1916 onwards

Possibly the most iconic of the four. BDR’s engines came from W. G. Bagnall of Stafford—powerful 0-6-4T locomotives that puffed across 97 km and 23 stations.

These engines had a strange connection to Egypt. During World War I, a few 2-6-2T locomotives—initially built for the Egyptian Delta Light Railways—were diverted here. (McLeod Rail)

BDR lived long in Bengali imagination. In Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay’s Hansuli Banker Upokatha and Ganadebata, the BDR line runs like a living character. Even Rabindranath Tagore travelled by this line after his Nobel Prize, at McLeod’s invitation. (McLeod Rail)

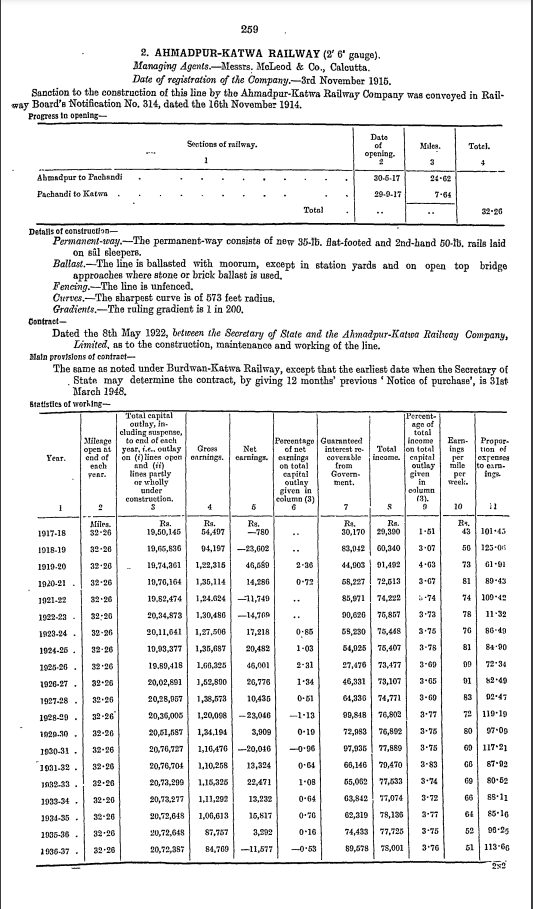

3. Ahmedpur–Katwa Railway (AKR) – 1917

A 52-km stretch connecting 16 stations, opened in two phases.

This line passed through pastoral Bengal—fields, ponds, palm trees, and villages where time moved slower.

AKR later became famous again for a different reason: it was one of India’s last surviving narrow-gauge passenger lines before conversion. (McLeod Rail)

4. Kalighat–Falta Railway (KFR) – 1917 to 1920

The only McLeod line that touched Kolkata.

Imagine this: A 2 ft 6 inch line weaving through Behala, carrying people to the riverside town of Falta.

KFR also boasted something rare—the first use of three brand-new AK16 locomotives from Bagnall’s Castle Engine Works.

If you travel through Behala today, the bustling James Long Sarani stands where the tiny train once chugged along.

When Railways Became Part of Life

The magic of McLeod’s lines wasn’t in their machinery. It was in the stories.

Villagers say the train would stop anywhere if someone waved. One legendary tale speaks of an old woman who flagged down the driver—and he happily gave her a lift, ticket or no ticket. (McLeod Rail)

Farmers sent vegetables through passengers. Pilgrims used them to visit Shaktipeeths.

Children ran beside the tracks, chasing the engines like they chased dreams.

In many places, the railway track passed right beside kitchens, courtyards, and ponds. If a driver knew that a wedding was happening in a village, he slowed the train—just out of courtesy. (Indian Railways)

These weren’t railways.

They were neighbors. (McLeod Rail)

The Beginning of the End

By the 1950s, trouble began.

The world was speeding up, but McLeod’s trains were not. Delays grew. Losses mounted.

In 1957, McLeod announced they couldn’t continue KFR anymore—the loss was ₹3.17 lakh a year, a huge sum for that time. The line was shut. Its engines went to museums.

By the 1960s, nationalization changed everything.

AKR, BKR, and BDR were transferred to Indian Railways between 1965–66. But they survived a few more decades—slow, loved, familiar. (McLeod Rail)

Then came broad-gauge conversion.

- BDR closed in 1995, reopened as broad gauge in 2005

- AKR closed in 2013, opened again in 2018

- BKR shut down permanently on 1 December 2014

And with that, an era ended.

What Remains Today

A few locomotives sit in museums. Some station boards fade quietly under the sun.

But memories—those are still loud.

Villagers still talk about the “toy train” that once ran through their homes. Writers still romanticise the whistles that echoed across Bengal’s fields. Elderly commuters still recall how simple it all felt.

McLeod’s lines were never giant engineering marvels. They never carried armies or changed empires. But they changed lives, softly. (McLeod Rail)

They proved one thing Karl Marx hinted at long ago—railways don’t just move goods. They move people, cultures, ambitions, dreams.

And sometimes, even a tiny train can carry a century of stories. (McLeod Rail)

Photo Courtesy: Author

By day, Amlan Chakraborty a technical architect in IT; by passion, he's an explorer, travel writer and photographer. During his travels, he savors the journey on foot or via public transport, immersing himself in the local culture at street food joints and book corners. Through his lens, he captures and shares the essence of nature, humanity, and cultural and socio-political moments.