How Interpretive Power Is Quietly Changing Hands

Sandra Day O’Connor’s 1981 Supreme Court nomination was historic: the first woman justice. Yet the scene that confirmed her was entirely predictable: the ABA (American Bar Association) evaluation committee consisted of fifteen white men, the Senate Judiciary Committee questioning her featured eighteen white men, and constitutional interpretation remained what it had always been, the exclusive province of a demographically narrow elite. It’s worth remembering that until 1975, Supreme Court justices didn’t even have permanent law clerks who were women, a small but telling detail of the old guard.

Forty-three years later, when Ketanji Brown Jackson faced confirmation, three of the eleven Democratic Judiciary Committee members were non-white, and her former law clerks represented the most diverse cohort in Supreme Court history. The resistance was fierce precisely because everyone understood what was happening: America’s constitutional authorship was changing hands.

This essay argues that constitutional power is already changing hands—quietly, structurally, and irreversibly.

This transformation represents more than demographic evolution or political symbolism. It constitutes America’s most significant epistemic shift since the founding era. The gradual transfer of constitutional interpretive authority from its historical gatekeepers to a broader, multiethnic coalition.

The implications extend far beyond who sits on which court; they reshape how constitutional meaning itself gets constructed, defended, and transmitted across generations.

The Old Order

Constitutional power was never distributed democratically. It concentrated among those who controlled the interpretive machinery, federal judges, Supreme Court clerks, state attorneys general, legal scholars, and the elite institutions that credentialed them.

Through 1980, this interpretive class maintained striking demographic consistency: overwhelmingly white, predominantly Protestant, educated within an exclusive institutional pipeline running from elite undergraduate schools through Harvard, Yale, and Columbia Law, prestigious clerkships, and eventual appointment to senior judicial or administrative roles. There’s a telling piece of trivia: for decades, the Harvard Law Review presidency, a near-guarantee of a Supreme Court clerkship, was almost exclusively held by white men. That didn’t change until the 1990s.

Also Read: Puppet in the Hands of Fate: A Memoir from the Margins (Part: 1)

The numbers tell the story starkly. From 1950 to 1980, Supreme Court law clerks were 95 percent white and male. Through 1967, no non-white judges sat on federal appeals courts. In 1970, women comprised just 5 percent of law students and 3 percent of practicing attorneys. Elite law school faculties remained 90 percent white through 1990.

This wasn’t accidental exclusion, it was systematic gatekeeping that treated constitutional interpretation as the natural domain of a particular demographic profile. The system’s exclusivity served a function: it ensured interpretive coherence through shared cultural reference points, educational experiences, and professional socialization. When constitutional meaning was contested, the interpreters shared enough common ground to reach workable consensus.

The homogeneity was a feature, not a bug.

The Great Opening

That ecosystem is now undergoing systematic transformation across every institutional layer simultaneously. At Harvard Law School, the 2023 entering class was 51 percent students of color; Yale Law reached 50 (2024 intake) percent. These aren’t mere admissions statistics, they represent tomorrow’s constitutional interpreters moving through the pipeline toward federal clerkships, Department of Justice honors programs, and eventual judicial appointments.

Constitutional succession is not only vertical but horizontal, spread across states where lived diversity intersects with constitutional enforcement. Consider the small-town lawyer who grew up navigating language barriers now interpreting bilingual ballot requirements, that’s constitutional interpretation in action.

The change cascades upward through each career stage. Supreme Court clerkships have diversified dramatically. Justice Jackson’s chambers exemplify this shift: her clerks include graduates from Howard University Law, not just Harvard. It’s a quiet revolution, imagine a Howard graduate helping draft an opinion that could shape voting rights, bringing a historically Black university’s perspective into the nation’s highest court.

Also Read: Puppet in the Hands of Fate: A Memoir from the Margins (Part: 2)

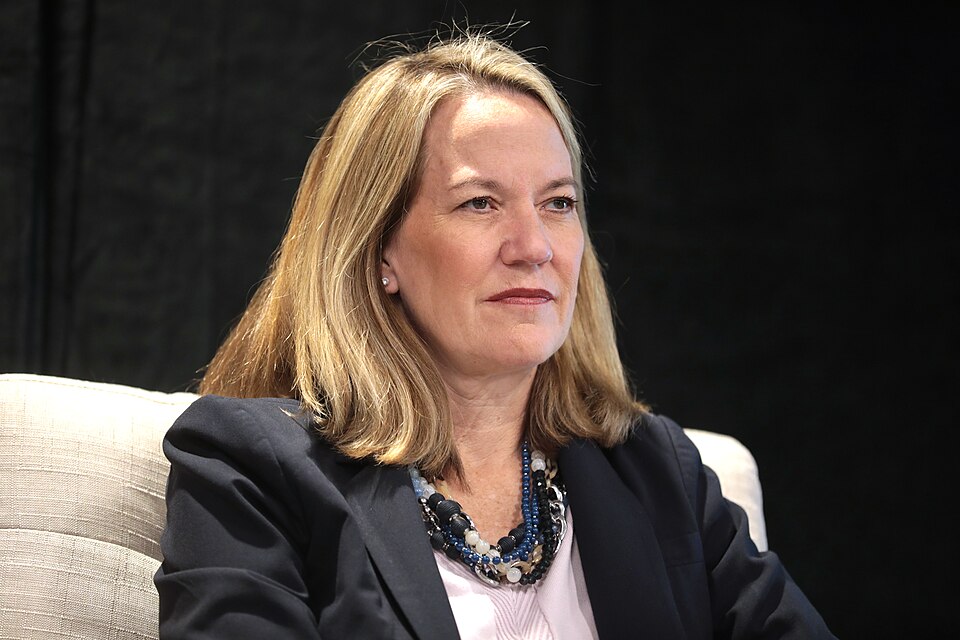

State-level positions where constitutional interpretation happens daily, election administration, attorney general offices, state supreme courts, reflect accelerating demographic change. Georgia’s 2022 Secretary of State race featured an African American Republican nominee. Arizona’s current Attorney General is Latina. These aren’t symbolic appointments; they represent operational constitutional authority. Picture a Latina attorney general deciding whether a new state law infringes on free speech, drawing on her community’s historical experience with censorship.

The synchronization across institutional layers matters enormously because constitutional interpretation operates through professional networks, clerks become professors, professors advise judges, judges cite academic scholarship. When these networks diversify simultaneously, interpretive frameworks inevitably evolve.

When Diversity Becomes Doctrine

Skeptics raise a legitimate question: does demographic change necessarily produce interpretive change? After all, professional socialization within elite legal institutions might homogenize perspectives regardless of background.

But Sonia Sotomayor’s 2016 dissent in Utah v. Strieff offers a counterpoint. She cited James Baldwin and Ta-Nehisi Coates to describe the “civil death” imposed by routine police stops on people of color. This wasn’t a rhetorical flourish, it was constitutional reasoning infused with lived experience, a jurisprudential move unthinkable in O’Connor’s confirmation era. Here, demographic representation reshaped not just who was speaking but what constitutional law could sound like, what registers of moral authority it could invoke.

A similar expansion unfolded in Shelby County v. Holder (2013). Chief Justice Roberts gutted the Voting Rights Act’s preclearance provisions, appealing to “equal sovereignty of states.” Yet the dissent, led by Justice Ginsburg, leaned heavily on evidence assembled by Black and Latino coalitions in lower courts, documenting contemporary voter suppression. That evidence reframed the constitutional debate. What had once been litigated as abstract federalism was recast, through diverse legal advocacy, as lived disenfranchisement. The interpretive field itself widened.

And outside Washington, the shift is equally visible. In 2023, Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes established an Office of Election Integrity staffed partly by lawyers who were the first in their families to attend college. That office now adjudicates constitutional meaning in real time, not in law reviews or judicial chambers, but in precinct-level disputes that determine who votes and whose votes count. Constitutional succession is not only vertical but horizontal, spread across states where lived diversity intersects with constitutional enforcement. Consider the small-town lawyer who grew up navigating language barriers now interpreting bilingual ballot requirements, that’s constitutional interpretation in action.

Photo Courtesy: AI, picryl.com, nara.getarchive.net, Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Commons

Gunjon Dasgupta writes about power, technology, and the cost of justice. His work includes The Ananya–Rudra Series, a political thriller, and essays bridging Ambedkar's moral philosophy with contemporary political economy. He lives in Kolkata.