I learned Hindi at Osaka University of Foreign Studies (which was recently integrated into Osaka University) from three professors: two were Japanese and one was a native Indian who is a grandson of Madan Mohan Malaviya, the founder of Banaras Hindu University as well as an independent activist under British rule.

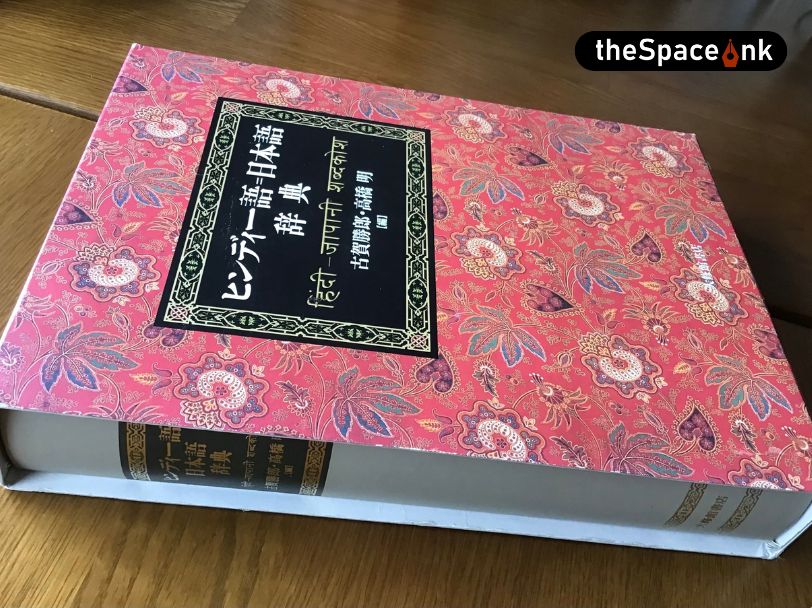

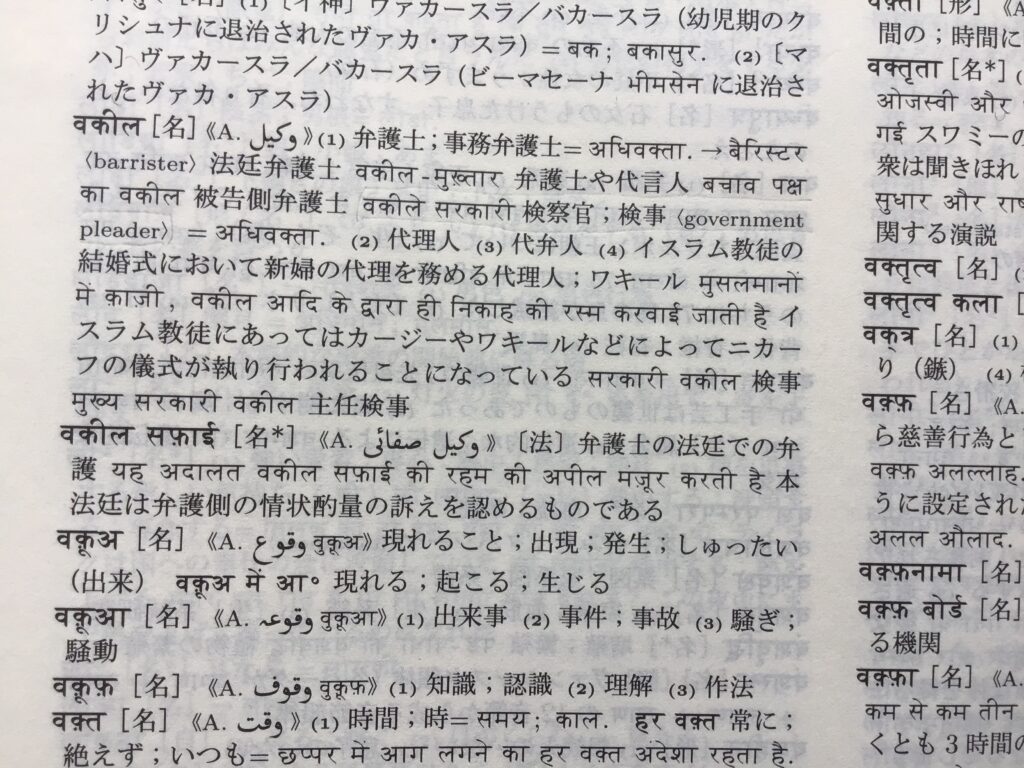

One of the Japanese professors was awarded The Order of The Rising Sun by the Government of Japan for his lifelong dedication to publishing a comprehensive Hindi-Japanese dictionary. The other was conferred the Padma Shree by the President of India for his contribution to literature and education and also served as a legal interpreter of not only Hindi but other Indian languages such as Urdu, Bengali and Punjabi. They were also conversant in the respective literatures and histories of the aforementioned languages. This was way back in the latter half of the 1970s, and their achievements made them pioneers in this linguistic field among Japanese academicians.(Hindi)

After the excitement over the American and Soviet pavilions at the 1970 Osaka Expo, the Japanese yen, which had been fixed at 360 yen to the dollar since 1947, transitioned to a floating exchange rate system and became stronger in 1973. In the same year, we experienced the first oil crisis. During that period, the Japanese perspective was overwhelmingly Western-centric; India was out of sight.

I learned about democracy from a Hindi language class under the professor who used a textbook handmade himself

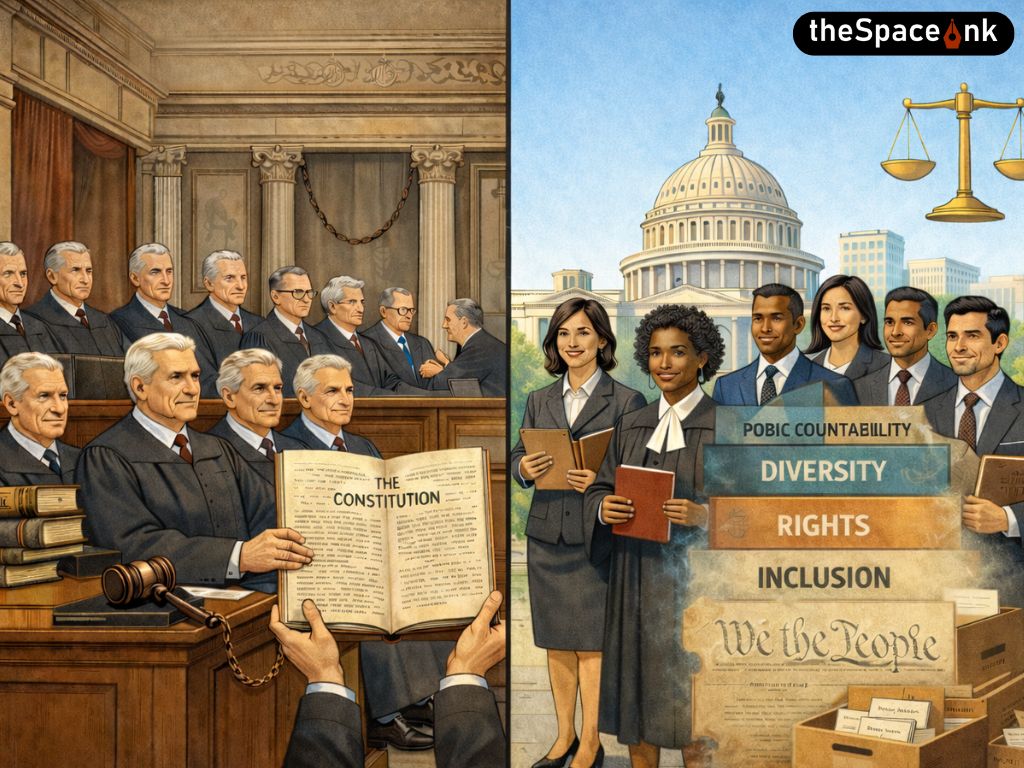

So, when I mentioned that India was a democratic country, they would often comeback with, “How is it possible to be democratic with the caste system?” In reality, India has had a Dalit or a minority Muslim president and elected a low-caste tea seller as prime minister. Furthermore, only India continues to use many different language scripts. And this is the democracy I was taught. I learned about democracy from a Hindi language class under the professor who used a textbook handmade himself. He used poor quality paper and it looked very unremarkable, but contained many meaningful sentences. The first sentence was, “I am a lawyer.”(Hindi)

In those days, English textbooks designated for Japanese junior high schools started with the sentence of, “This is a pen.” So, one student asked the professor why the word ‘lawyer’ should be taught at the very beginning. Then, the professor answered that it’s because in India, lawyers were more important than in Japan, and it was the lawyers who had played very crucial roles in the independent movements. This sentence was immediately followed by another that I cannot remember exactly in Hindi, but its meaning was too profound to forget. It was something like this: Democracy is to protect minority’s rights.(Hindi)

Read More: Recognizing Zainichi Korean Literature in Japanese

After its defeat in the Second World War, Japan was ‘reborn’ as a democratic country with a new constitution drafted by the US. However (therefore?), we didn’t understand what democracy was.

In 1970, I was in my first year of junior high school. One afternoon, we gathered sitting in a big room to discuss some controversial issue concerning us students. A boy acting as a chairman declared after a hasty discussion, and rather prematurely, that we should cast our vote. Since the issue was controversial, the difference between majority and minority was small. Several students were unsatisfied with the result as well as with the process to reach the conclusion. But, the boy claimed that once the issue got settled through a vote, then there’s no room for discussion anymore.(Hindi)

I remember his smirk. He belonged to the majority. I was a minority. I kept quiet, unlike some boys who objected to him. And because of this, I, as a preadolescent girl, gained the impression that under a democracy

“This is democracy,” he said, triumphantly. “We are the majority.”

I remember his smirk. He belonged to the majority. I was a minority. I kept quiet, unlike some boys who objected to him. And because of this, I, as a preadolescent girl, gained the impression that under a democracy, the minority has to follow the majority. And there’s no more chance to say anything further. Our teachers were there, but not a single one of them said anything; they only observed our activity. That discouraged me, too.(Hindi)

My professor told us that India was the largest democratic country in the world, from the perspective of its population, diversity, and constitution. I didn’t know that until I majored in South Asian Studies as a university student in the late 1970s.Those days in Japan, India was known as the developing Hindu country with the deep-rooted infamous ‘caste system,’ as well as being mysterious and religious that it attracted Western hippies. In fact, India has been pursuing secularism since its independence, a fact that most Japanese didn’t know.

Also Read: Hideo: From Japanese Appropriation to Appreciation

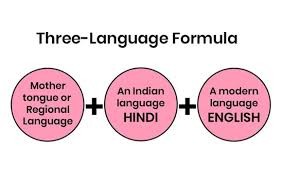

The misunderstanding and lack of knowledge about India was within the academic circle as well as among ordinary people. When the European Union adopted the three language policy among its member countries, my colleagues appreciated how progressive it was to promote languages other than English. I told them that India was as vast as Europe in area and integrated many diverse peoples into a single sovereign country of many different languages and scripts, and religions as well—and they shall be protected constitutionally for decades. I reminded them that they simply didn’t know about India. The concept of three language policy was not new to India. However, my colleagues were only concerned about Europe and America. These were the world for them for a long time.

It is only during the last 20 years or so that Japan has shown a significantly greater interest in India since the latter has stood out as one of the powerful leading countries in Global South. Here in Japan, some modern thinkers of the late 19th to early 20th centuries attempted but failed to abolish the complex Japanese writing system that’s comprised of two Japanese phonetic characters blended with Chinese ideogram. Under the Westernization process of Japanese society, some modernizers advocated the exclusive use of the Roman alphabet instead. Thanks to their failure, we can now read our classic literature and access our rich cultural references.

I appreciate that the Indian government prints texts on their currency, the Indian rupee note, using their own scripts. “The Right to be Different and the Right to be Treated Fairly” summarized the basic concept I learned in a Hindi language class almost half a century ago when India was regarded as a developing country by the world. Now, the world has caught up with India.

All Rights Reserved

Image Courtesy: Author

Reference:

Bindiya Bedi Charan Noronha, “The Right to be Different and the Right to be Treated Fairly,” August 21, 2022, Indian Periodical

Mayumi Yamamoto is a writer and academic based in Kyoto, Japan. Her poems have appeared in Literary Yard, and some opinions in Indian Periodical. She authored several published books in the Japanese language.