1

This 21st century in Japan, we witness more and more non-native Japanese speakers among us who express their thoughts and opinions in Japanese. Some of them even earn recognition as novelists or poets in our native language. However, that was not the case when I was young.

In my childhood, we had a few Japanese words to categorize non-Japanese people, one of which is gai-jin. We applied this word as the Japanese equivalent of Westerner. Gai-jin was mainly used to refer to Americans during those days. More precisely, the concept of gai-jin in our imagination was a person with blue eyes, brown hair and white skin.

We believed that they spoke only English and didn’t understand Japanese at all. It was not an exaggeration to say that we expected them to refrain from speaking Japanese. Whenever they spoke, in defiance of our expectations, surely their speech must have been awkward, and their scant vocabulary limited to only one or two words, because it was inculcated in us by our grownups that Japanese language was too special for any gai-jin to master it.

Levy Hideo landed in Japan when this was the dominant mindset among Japanese people. It was in the late 1960’s. He was in his teenage years and fell in love with Japanese language, which became his passion. He ended up becoming an American novelist writing in Japanese, after building his career as an awarded translator of the Man’yoshu (“Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves”), the famous anthology of ancient Japanese poetry.

He was born in 1950 and raised in the US as well as in Taiwan, Hong Kong and Japan. Biologically, he is of no Japanese descent, although his given name, Hideo, is a Japanese one after his father’s Japanese friend. His mother tongue is English, but he has been crafting his literary works only in Japanese.

It was in March 1987 that his first novel appeared in one of the established literary journals, Gunzo. However, this debut work had to await its due recognition from the Japanese literary establishment for half a decade, as it was finally honoured with the Noma Literary Award for New Writers only in December of 1992.

In between, he resigned from his position as a tenured professor at Stanford University in March 1990 and moved to Japan to settle down for further creative activities. In fact, during these five years,

Levy was consistently writing articles about the language and literature and trying to give voice to his unique identity: a Japanese language author with blue eyes and a Jewish-American family name. He was even actively in charge of a literary journal as a regular reviewer of currently published novels of Japanese authors before receiving the prize for a novice novelist.

Levy disclosed in his articles how he was treated when he started creating the original text in Japanese. That was as if, according to his words, a gai-jin was never permitted to have the “ownership” of the language. And a gai-jin could be, at most, its “leaseholder” eternally.

Actually, it was beyond our imagination back then that an English native speaker, more so of non-Asian descent, would embark on creative literary works in Japanese. Let me go back to history to analyze our reaction towards Levy.

2

In 1894, Prof. Kazutoshi Ueda of Tokyo Imperial University made his speech titled “Koku-go to Kokka to (National Language and Nation)”. In the speech, he declared, “The language is the spiritual blood of the nation.”

The Sino-Japanese War in the Korean peninsula was ongoing at that time. In the late 19th century, Japanese leaders harboured the idea of making the Japanese imperial territory a monolingual sphere.

Koku-go literally means national language, but in practice, this word referred to the Japanese language as used exclusively by the Japanese people among themselves—and not by and with non-Japanese peoples. Until today, this practice remains in the curricula of primary and secondary schools, with two names denoting the Japanese language as a subject: koku-go and nihon-go. (This should be discussed separately.)

Also Read: Linguistic Imperialism: English Conversation as Ideology

Based on this koku-go concept, we used to say koku-bungaku, instead of nihon-bungaku to refer to the Japanese literature. Furthermore, those two terms were often combined into koku-go koku-bungaku, which was used as the designation for a department under the faculty of letters/humanities of Japanese universities. This terminology was lined with koku-shi (a particular perspective of studying and teaching Japanese history) as well. We had another scholarly field called koku-gaku, the study of ancient Japanese thought and culture. Every academic study starting with koku- conveyed the categorical statement that the study should be only for the Japanese, by the Japanese and about the Japanese. Hence, they are completely different from Japanology or the Japanese Studies conducted and studied by Westerners.

Is it just incidental that gai-jin became the short form of gai-koku-jin, the official translation of “foreign national”? And was the second character -koku- that is in the original word intentionally dropped to remove any association with the Japanese people?

In other words, was the character omitted to declare that koku, which literally means “nation” or “state”, should be an identifier solely of Japanese people?

Actually, koku-go was considered to be exclusively for Japanese children to build their national identity, by fostering “Japanese-ness” nourished by koku-bungaku and koku-shi.

Once, the Japanese imperialist attempted to “convert” the Asian peoples under its rule into “Japanese nation” by implanting koku-go in their soil by force. That is why there are several Korean authors who are also native speakers of the Japanese language themselves. And in the 1970’s, their novels written in Japanese became controversial among Koreans in Japan.

Since literary works are strongly connected to the author’s identity, the writers and critics embedded in the koku-go koku-bungaku mindset could not accept the fact that Japanese, just like any other languages, can be mastered by any diligent and intelligent student—unless they were once Japanese subjects under the colonial rule.

Also Read: Once There Was A Country Called Soviet Union

That’s the reason why Levy had to wait for as long as five years to be awarded as a novice novelist in the Japanese literary circle.

3

In hindsight, the 1960’s and 1970’s were the transition period when Japanese society became more inclusive and prepared for the changing international circumstances. Starting with the “Project on Welcoming 100,000 Students from Overseas” under the Nakasone government in 1983, the population of non-Japanese residents increased, along with the arrival of a volume of “de facto” migrant labourers throughout the 1980’s. Japan had to “embrace” a multilingual society irrespective of resistance from some quarters.

After Levy was awarded in 1992, David Zoppetti, a Swiss-born author, received another literary prize in 1996 as a Western-originated exophonic writer of Japanese language.

In 2000, a new literary prize for which only non-Japanese students are qualified to apply was founded. Needless to say, this award encourages non-native speakers of Japanese to improve their linguistic and literary talents.

Arthur Binard and Jeffrey Angles, both Americans, followed in Levy’s footsteps, whose poems were awarded in 2001 and in 2016, respectively. Besides them, today, we have several non-native Japanese or bilingual writers originated in some Asian countries like China, Taiwan and Iran.

In 2011, the English translation of Levy’s debut work was published under the title of “A Room Where the Star-Spangled Banner Cannot Be Heard” by Columbia University Press, which says “He has become a major international voice in contemporary Japanese literature.”

References:

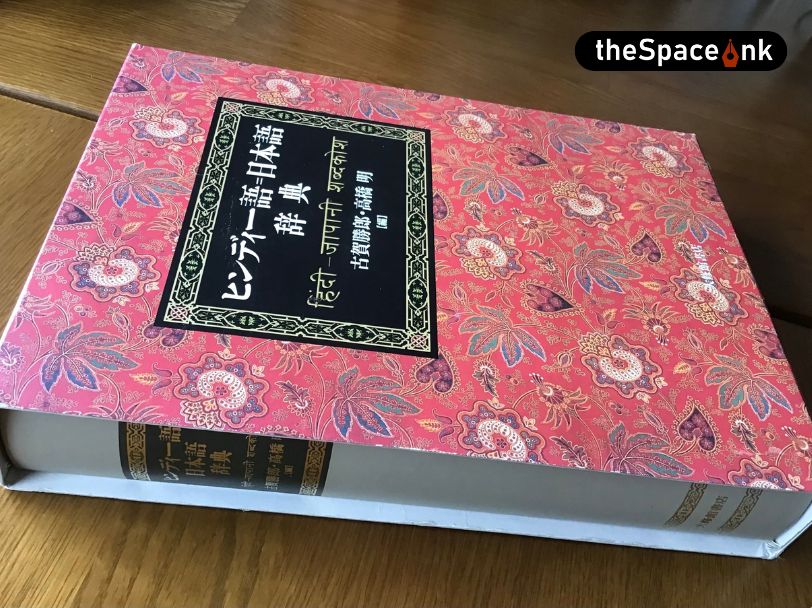

Yeounsuk Lee, “Kokugo to iu shiso,” Iwanami Shoten, 1996

(English version is published in 2009 by University of Hawaii Press, with the title of “The Ideology of Kokugo: Nationalizing Language in Modern Japan,” translated by Maki Harano Hubbard)

Levy Hideo, “Nihongo no shori,” Kodansha, 1992

Levy Hideo, “Nihongo wo kaku heya,” Iwanami Shoten, 2001

Image Courtsey: Kyoto Journal, National Book Foundation, Flickr

Mayumi Yamamoto is a writer and academic based in Kyoto, Japan. Her poems have appeared in Literary Yard, and some opinions in Indian Periodical. She authored several published books in the Japanese language.