I only managed to survive Cambridge, to be honest, because I played cricket. True, it was not the only sport I played there, nor was it even the first: I had arrived in the autumn of the year, and that could only mean one thing: we started with football. It was bitterly cold, and at the end of the first half of the first game I played, I couldn’t feel my hands. Fortunately, I had a pair of gloves in my coat, which I had left in the changing room, and thereafter, I played with gloves on. Came the spring, and in April I turned out for my first cricket match of the season, a ‘friendly’ that was played in distinctly hostile conditions: my hands were still frozen, the first ball I bowled was a rank long-hop that was duly despatched over mid-wicket for six, and the second, which I landed in the right place, was hit straight back at me and struck me in the sweet spot of the right palm; but my hand was too frozen to close on it and complete the catch. I learned that the best place for hands in between balls (and overs) was in your trouser-pockets.

Cricket was the only part of Cambridge that was truly civilised: the carefully-mown lush outfields a far cry from the hastily-selected patch of territory that every group of cricket-players had to hustle for themselves in the early hours of a morning on the Calcutta Maidan, the boundaries approximate and by mutual agreement (or disagreement), the pitches actually providing an even bounce and changing playing conditions that were not the result of the stray pebble the ball had struck. And you could take catches in the slips without taking all the skin off your forearms. ‘Twas a wondrous thing; and the gentle leisure of an all-day one-innings game allowed one the luxury of batting long as a form of meditation: the worst that could happen was the necessity of batting second against a team whose bowling consisted of slow stuff that was harmfully unpredictable, exposing you to all the dangers of a momentary lapse of concentration that would give the bowler your wicket. Inevitably, one full toss or long hop too many would tempt you into an indiscretion that would expose the tail to the one regular fast bowler in their team, who would bound in with renewed enthusiasm once your top order had succumbed.

In India, in limited-overs university knockabouts, I had been a bowler who gave up on the big leg-break because wicketkeepers missed them as often as batsmen did, and that leaked runs, even if not to my name: I developed a cramping top-spinner and googly that didn’t let a batsman free his arms. With the less violent bats of those times, spinners went for less runs as batsmen (as they were still called) actually had to time the ball to clear even a shorter boundary.

By contrast, in club games, often on dust bowls, I could be a very effective wicket-taking leg-spinner (I had two hat-tricks to my name at Vivekananda Park, but at least three of those wickets I could attribute to the ball having spun a speck of dust into the batsman’s eye as he came forward to meet it).

Batting was a shortened experience, and I hadn’t developed the patience for long innings, as I could usually hold my place in a side with my bowling – and, for a time, as a wicketkeeper. In England, for one team I became an opening batsman with an average of around fifty; for another, a leg-spinner; and for still another, a bit of both, and I was usually a number six batsman, which tested my patience a lot more than opening the innings did. The meditative ability to open the batting and to stay in for most of the day if you could – limited only by your lapses in concentration – was a great help to a young researcher who could use the discipline and concentration of an opening batsman and put it to good use in his day job as research student. And of course that applied the other way around, too. A short-handled, narrow-grained Gray-Nichols Sabre was the bat that accompanied me through those years. It belonged to Trinity College, though I had selected it myself; I still greatly regret refusing to take it with me as a farewell present when the team, in an act of generosity, offered it to me as departing captain at the completion of my PhD.

It was also in England that I learned the meaning of an old and by-then officially defunct distinction: Gentlemen versus Players. I was playing for Trinity College, and in my first year I’d been more than a useful winter nets bowler for the university trials, so I knew there were several people on the team who knew I could play. But when the first games (early-season friendlies) came around, I was mostly not on the team lists, though I got a game or two. By the end of the first three or four weeks of the season, I’d begun to understand. ‘Friendlies’ were played among friends, who had been to public school together; they weren’t meant to be serious games. As the season progressed, and ‘cuppers’ games began, my phone would ring: three games a week for the Players, who were needed to keep a team’s hopes alive. Oh, and – Players would bowl, mostly. The Gentlemen would bat. The annual Gentlemen versus Players fixture on the first-class cricket calendar at Lords had long been o’erthrown, as a relic of a by-gone feudal era, where the Gentlemen were amateurs and the Players were professionals, and had, consequently, different social standings in and out of the game. But its residues were to be found on the playing fields of Cambridge. I did my bit as a Player, and I even made it to the Annual Register’s yearly cricket report with figures of four for nineteen in a crucial match; but they didn’t spell my name right.

Also Read: Three Poems

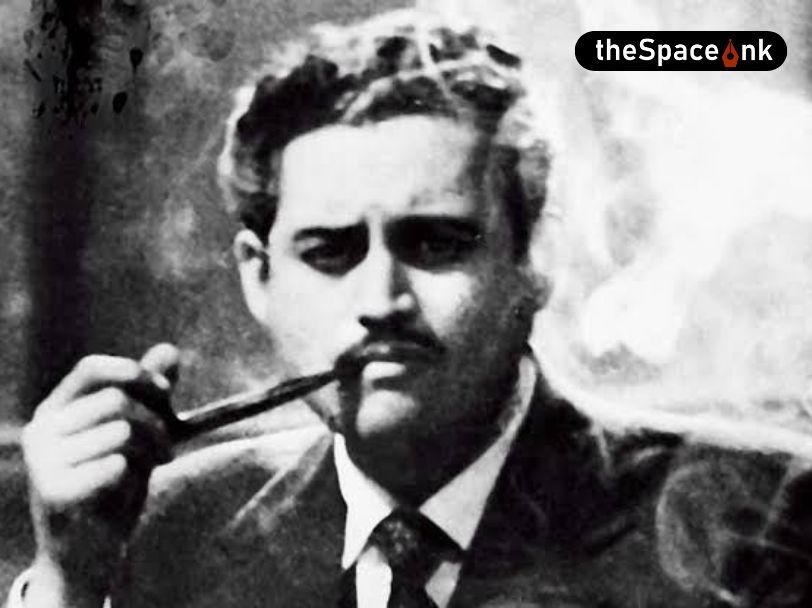

And the social history of cricket in Cambridge might well have been of interest to the great historian and cricketer, CLR James: what do they know of cricket, who only cricket know?, he asked, echoing Rudyard Kipling.[1] In the early 1990s, South Africa had only just ended apartheid; Zimbabwe had been independent since 1980, and was still dominated by white landowners. My first captain at Trinity, an undergraduate then, and a man who went on to play Test cricket for Zimbabwe, knew how to fly an airplane, because, as he told us, it was hard to get from one end of his lands to another without one. In another team I played in, one of my co-bowlers came from a family that had been architects of the South African apartheid system; he, and his family, were charming, polite, cultured people with no hint of apparent prejudice: we were friends, and I don’t remember him participating in one or two of the heated discussions about the end of apartheid, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and the future of white property in the new South Africa that happened in the dressing-room between innings. Cricket, as we’ve often been told, is a metaphor for empire, race, class, status, and a lot more; we make up our metaphors as we go along.

[1] CLR James, Beyond a Boundary: A Social History of West Indies Cricket (1963), Preface.

All Images: Wikimedia Commons

Benjamin Zachariah works at the Georg Eckert Institute for Educational Media in Braunschweig, and with the project on the contemporary history of historiography at the University of Trier. He was trained in the discipline of history in the last decade of the previous century. After an uneventful beginning to a perfectly normal academic career, he began to take an interest in the importance of history outside the circle of professional historians, and the destruction of the profession by the profession. He is interested in the writing and teaching of history and the place of history in the public domain.