“He is there where the tiller is tilling the hard ground and where the path-maker is breaking stones. He is with them in the sun and in shower, and his garment is covered with dust. Put off thy holy mantle and even like him come down on the dusty soil! (Tagore, Gitanjali, 1912)

From the time when Man became truly conscious of his own self he also became conscious of a mysterious spirit of unity which found its manifestation through him in his society.” (Tagore, ‘Man’s Nature’, The Religion of Man, 1930)

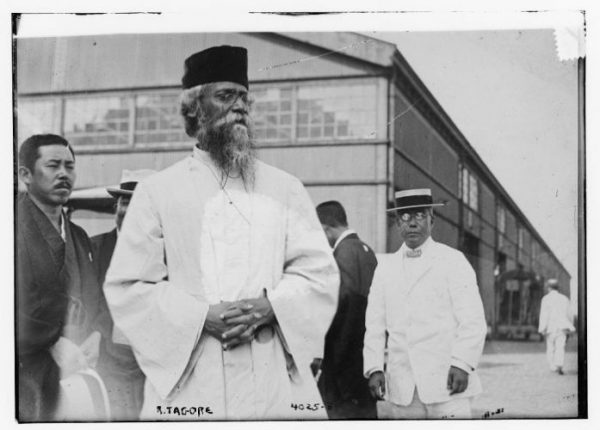

Rabindranath Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for his Gitanjali, Song Offerings. The celebrity he enjoyed for a few years provided him with opportunities to travel widely and speak out to the world through his lectures. These lectures were subsequently published as collections of essays: Sadhana (1913), Nationalism (1917), Personality (1917), Creative Unity (1922), Talks in China (1924) and The Religion of Man (1931).

These six books represent what Rabindranath wanted to communicate to the West, at the time, out of concern for the direction in which Western nations were taking over the rise of nationalism as a dehumanising apparatus of power and greed. Rabindranath Tagore’s challenge was for the West and the East to embrace humanity and to recognise that aspect as the essence of Man’s universe. His hope was to work for that goal with the help of a new education.

We all know that Rabindranath Tagore was primarily a poet. What we do not know well is that he was the founder of a new education system and worked relentlessly for it. He founded a school at Santiniketan in 1901 and added to it an international university in 1921, as also an institute of rural reconstruction named Sriniketan in 1922. Together he named the institution Visva-Bharati. Visva-Bharati International University was endowed with a Vedic vision, yatra viswam bhabate eka nidam, ‘where the world meets as in a single nest’.

The making of this institution was central to his national and international concerns throughout his life. It was an education which sought to work for a common humanity, locally and globally, in an institution unhindered by the territorially bounded model of the nation-state. This venture was, as it were, for India’s entry into the universal.

Rabindranath Tagore’s lifelong endeavour with education in a tiny corner of rural Bengal was intimately connected with his ideals of a non-parochial and inclusive nationalism. He was not apologetic about the small scale of his work given his single-handed resources. His primary aim was to establish an ideal for his country through his ideas for a new education. But the ideal was never ever left without its relevant action. Tagore’s ideals were never merely just beautiful thoughts without any practical outcome. He was an inexhaustible man of action.

It may not be out of place here to bring in a live assessment of this education from a celebrated alumnus of the Santiniketan school, the Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, who studied in the Santiniketan school. “I am personally rather partial”, Sen writes, “to seeing Tagore as an educationist, having been educated myself at Santiniketan. What he valued most about his studies in the Santiniketan school was that it was a celebration of “variety”. Sen has referred to the ease with which discussions in the Santiniketan school ranged from Indian traditional literature to the contemporary, to the traditions of China, Japan, South East Asia, to classical Western thought. Tagore’s distress over his own country was about the cultural conservatism and separatism that tended to grip India from time to time.

Tagore was heard by huge audiences in the West, sometimes with no standing room in the halls. He was completely serious about what he wanted to represent or communicate. He communicated similar thoughts regularly to his own Santiniketan community of teachers and students. The talks or sermons in Bengali are available in a collection titled Santiniketan and in another more institutionally focussed collection titled Visva-Bharati. His ideas of a meeting of East and West were very serious in his life’s goals and actions. He wrote that God had willed him for this mission.

Let me now examine this particular paradigm by pointing to the thoughts shared by Tagore and some other thinkers of his day. Firstly, there was a growing disenchantment over the West’s civilisation, particularly after World War I, and a brewing protest against the exploitation of the East by the West.

Tagore’s lifelong endeavour with education in a tiny corner of rural Bengal was intimately connected with his ideals of a non-parochial and inclusive nationalism. He was not apologetic about the small scale of his work given his single-handed resources. His primary aim was to establish an ideal for his country through his ideas for a new education.

He argued that the interaction of the civilizations of China and India had the potential to balance the aggressive values of the West. Among his contemporaries in the farther East was Okakura Tenshin of Japan whom Tagore personally knew. He admired Okakura’s book, The Ideals of the East. Another like-minded contemporary was Zhang Taiyan of China. These thinkers were founders of an Asian cosmopolitanism searching for alternative values in sources other than the nation state and material culture. Okakura’s and Zhang’s worldview were close to Tagore’s, except in his opposition to their position that nationalism was a necessity till the goal of universal civilisational truths is reached. But Tagore made no concession for nationalism.

Born and brought up in the dislocation of colonial times but deepened by an intuitively cosmopolitan family, Tagore was given to thinking seriously about the West and about his own India from a young age. He wrote, for example, about the West:

There are grave questions that western civilisation has presented before the world but not completely answered. The conflict between the individual and the state, labour and capital, man and woman; the conflict between the greed of material gain and the spiritual life of man, the organised selfishness of the nation state and the higher ideals of humanity; the conflict between all the ugly complexities inseparable from the giant organisations of commerce and the state, and the natural instincts of man crying for simplicity and beauty and fullness of leisure – all these have to be brought to a harmony in a manner not yet dreamt of.

In India’s history of learning to live with the differences, Tagore saw an ideal of unity that could become a transcendence for India’s and Asia’s contribution to the new age. The mentality of the world was in need of a transformation to meet the challenge of the new age. He therefore spoke out for higher ideals in politics for the sake of humanity. He wrote,

Even though from my childhood I have been taught that idolatry of the nation is almost better than reverence for God and humanity, I believe I have outgrown that teaching, and it is my conviction that my countrymen will truly gain their India by fighting against the education which teaches them that a country is greater than the ideals of humanity.

All of these ideals of looking beyond narrow domestic walls went into the making of the Santiniketan education. It was hoped that the holistic values imparted to the students would help to build a ‘new’ Indian personality who would be ‘free’ from the conflict of communities and capable of appreciating the many currents of the Indian cultural tradition along with absorbing the humanistic and liberal values of the West. He gave an important place in Visva-Bharati University’s research agenda to the study of the mediaeval seers and sages of India such as Kabir, Nanak, Dadu, and others, who swept the country with a progressive movement by their forceful message – ‘he alone knows Truth who knows the unity of all beings’.

Visva-Bharati’s curriculum offered the coordinated study of the various cultural streams of the Indian civilisation– Vedic, Puranic, Buddhist, Jain, Islamic, Semitic, Sikh and Zoroastrian, through the multiple disciplines of philosophy, literature, art and music. My view of this endeavour for a new education is that through it Tagore hoped for a world which would move on from nationalism, patriotism, statism.

He emphasised there was to be no question of East or West where knowledge was concerned. Access to the World’s fountain of knowledge was essential. Imperial rule had restricted India’s entry into that arena. Visva-Bharati was conceived to break out of that isolation. That was his ‘other’ concern for a new education that was founded on the goal to connect his country with the gateways of the World’s learning. He wrote,

India has been cut off from the world’s scholarship, treated only to trifles in the name of education and relegated to a perennial primary school. We now want freedom from this spiritual and intellectual humiliation.

He believed that connecting with the World would be the self-respecting way of countering the humiliation of colonisation. The need of the day was for cooperation, he wrote, cooperation among ourselves as a nation, and cooperation with the World. Our country is crying out to her own children for their cooperation in removing obstacles in our social life that had destroyed our self-esteem. His grass roots level work for village reform in the villages surrounding the Santiniketan school was to retard what would otherwise lead to his country’s racial suicide.

Images courtesy: Picryl, Wikimedia Commons

A historian and Tagore biographer who is a former professor of The Indian Statistical Institute. Friendships of 'Largeness and Freedom', Andrews, Tagore and Gandhi: An Epistolary Account, 1912-1940, Rabindranath Tagore an Illustrated life, Santiniketan and Sriniketan are some of her celebrated works. She is a noted Tagore scholar and biographer.