Once, one of my friends mailed me a short story asking me to read it and make whatever changes I thought it required before he could send it for publication in the annual magazine of the educational institution where he was a student. It was the first story that he ever wrote. After reading the story carefully, I told him that in my opinion, his writing did not measure up to a good short story because it fell short of certain basic literary parameters that make a good story. I also told him that if it had to be turned into an absorbing story, he had to conceptualize and rewrite it. Therefore, I said, I would not be able to correct it but only rewrite it for which I did not have the time.

As expected, my friend was disappointed with my comments. He sent the story to the student editorial team headed by one of their professors. A month later, my friend walked up to me with a copy of their college magazine with his story printed in it. “See,” he said with a sense of indignant triumph, “my story that you rejected as a bad story has been published in our college magazine, what have you to say now?”

After congratulating him on his publication, I told him with a smile in a lighthearted manner, “Remember that the decision of the editorial team of your college to publish your story does not necessarily mean that it is a good story. Similarly, if the editorial team had decided otherwise, it does not mean that it is a poor story either. The merit of a story has to be analyzed based on certain literary parameters and not based on whether or not it is published.”

On another occasion, another friend of mine mailed me one of her poems asking for my evaluation of the poem. After having read through it, I told her in my typical ruthless plain-speaking way how I thought it was a piece of poor verse. A hard-nosed comment I regretted ever since! As you would expect, my comment resulted in the collapse of the literary bridge that had existed between us for a long time. However, I am happy to state that she is a gifted writer with many published good poems and stories to her credit. She writes well and is well-appreciated by her readers and the academia.

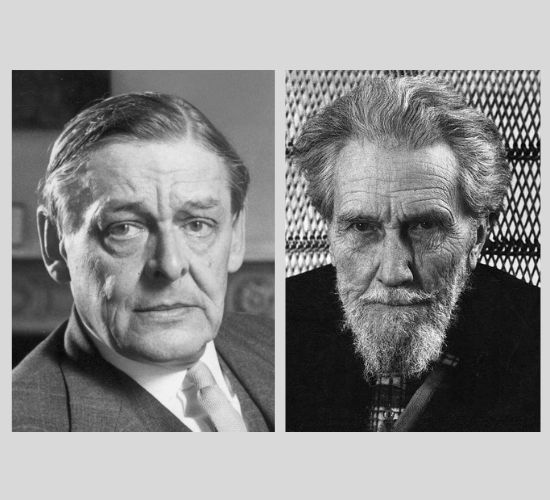

For the sake of greater poetic freedom, by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, conventional metrical poetry began to give way to what came to be known as modern poetry written in free verse that does not follow regular rhythm and rhyme. Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Gustave Kahn, William Carlos Williams, Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, etc. are all great practitioners of free verse. However, free verse is not free of rhythm; it tries to render the rhythm of natural speech to the idea it embodies by means of ingenious uses of rhythmical phrases and pregnant pauses. Its non-adherence to a strict metrical pattern provides much poetic freedom to write compelling verses with irregular line lengths. As D.H. Lawrence notes, free verse lets poets “get rid of the stereotyped movements and the old hackneyed associations of sound and sense.” Poetic freedom such as this, allows poets to give their own desired avant-garde shapes to their poems.

Trying to call our attention to the challenges and risks associated with free verse, Robert Frost says that writing free verse is like “playing tennis without a net.” Ironically, the inability of some aspiring poets to write conventional meted poetry and their desire for shortcuts to poetic heights through free verse (taking it for granted that free verse is free for all literary world), some prefer to write poetry in free verse. They should realize that as T. S. Eliot warned, “No verse is free for the man who wants to do a good job.” In other words, writing good poetry in free verse demands a high level of skill and craftsmanship. Certainly, free verse is not an easy way to shortcut one’s path to poetic success and popularity.

However, in India today we notice the proliferation of a lot of poets who write what I humorously refer to as inferior prose cut into shorter lines as supposed modern poetry in free verse. A good number of such poems are neither good free verse poetry nor prose poetry, both of which have their own parameters. Wallace Stevens begins his free verse poem, “Of Modern Poetry,” by saying that modern poem is “The poem of the mind in the act of finding/What will suffice.” Talking about the character and function of modern poetry he goes on to write in the same poem:

It has to be living, to learn the speech of the place.

It has to face the men of the time and to meet

The women of the time. It has to think about war

And it has to find what will suffice. It has

To construct a new stage. It has to be on that stage

And, like an insatiable actor, slowly and

With meditation, speak words that in the ear,

In the delicatest ear of the mind, repeat,

Exactly, that which it wants to hear, at the sound

Of which, an invisible audience listens,

Not to the play, but to itself, expressed

In an emotion as of two people, as of two

Emotions becoming one.

The arresting economy of words, the creative use of syntax, the stunning conciseness, the impressive cohesiveness, the controlling emotions, the evocative imagery, and the complex symbolism lending themselves to layered subtexts are some of the defining characteristics of the poetry written in free verse. Unfortunately, they are not the forte of much of what is passed off as modern poetry in free verse today. W. B. Yeats makes us aware that writing poetry is more difficult a job than performing backbreaking domestic labor or toiling arduously in a quarry when he writes the following lines in his poem, “Adams’ Curse.”

And scrub a kitchen pavement, or break stones

Like an old pauper, in all kinds of weather;

For to articulate sweet sounds together

Is to work harder than all these, and yet

Be thought an idler by the noisy set

Of bankers, schoolmasters, and clergymen

The martyrs call the world.’

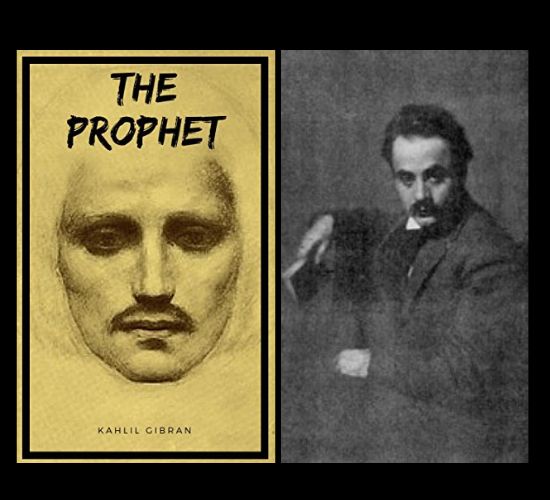

Lacking conventional line breaks and the visual structure of verse poetry, prose poetry adheres to the structure of prose paragraphs. Combining elements of both prose as well as poetry, it blurs the boundaries between the two forms. However, it employs poetic devices such as evocative and rhythmic language, copious images and symbols, and heightened emotional intensity. In order to tell stories, describe events and situations, depict emotions, or explore concepts, it often employs the narrative approach of prose fiction. However, it employs the condensed and crafted language associated with poetry. A typical prose poem can be as short as a few sentences or as long as several pages. Combining the richness of poetic language with the narrative potential of prose, prose poetry creates a unique literary form. French poets Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud, Lebanese-American poet Khalil Gibran, and Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore are some of the celebrated writers of prose poetry.

Many self-styled versifiers tend to bypass the demands of free verse as well as prose poetry because of their lack of poetic craft and skill. In general, these versifiers are quite unwilling and even afraid to submit their poetic output to informed literary criticism. This avoidance perhaps stems from their reluctance to subject their work to rigorous literary criticism, reflecting a certain degree of insecurity about their creations. Instead, they seek validation and comfort in mutual admiration, forming supportive circles where they promote one another’s works without the critical evaluation they may need. This trend is particularly prevalent in academic circles, where the pursuit of literary excellence may sometimes be overshadowed by the pursuit of praise and recognition.

Many self-styled versifiers tend to bypass the demands of free verse as well as prose poetry because of their lack of poetic craft and skill. In general, these versifiers are quite unwilling and even afraid to submit their poetic output to informed literary criticism. This avoidance perhaps stems from their reluctance to subject their work to rigorous literary criticism, reflecting a certain degree of insecurity about their creations.

If Ezra Pound had mollycoddled T. S. Eliot when the latter sent his poem, “The Waste Land” to the former for his editorial suggestions, both friends together would probably have given the world “The Waste Land” that could have been a waste of time. Pound made considerable cuts to the original manuscript with his editorial poetic knife removing lines and sections that he considered superfluous or irrelevant. To introduce depth and complexity to the poem through the intertextual method, Pound suggested the inclusion of a wide range of literary, mythical, historical, and cultural references, ranging from the classical to the contemporary period. He proposed significant alterations in the structure of the poem dividing the narrative under different thematic headings. Much of the poetic depth and elegance “The Waste Land” boasts of with regard to its refinement in language, diction, imagery, symbolism, modernist techniques, avant-garde style, and theme was also achieved on account of Pound’s seasoned editorial recommendations. At its publication, the poem turned out to be a groundbreaking literary masterpiece of the twentieth century.

The literary masterpiece, “The Waste Land” is a testament to the fact that a writer’s craft is honed by the critique they receive. Avoiding constructive criticism can lead to complacency and mediocrity, resulting in mediocre artistic output. The artist must never sidestep the critic.

To grow as an artist who can make a lasting impact in the world of literature, one must certainly possess genuine erudition, a desire for excellence, and unwavering dedication to his craft. Along with all these, one must have the humility and willingness to accept constructive criticism.

Sacaria Joseph is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at St. Xavier’s College, Kolkata. Having pursued his undergraduate studies at St. Xavier’s College, he furthered his academic journey by obtaining a Master of Arts degree in English Literature from Pune University, a Master of Philosophy from Jadavpur University, Kolkata, and a PhD from Visva-Bharati University, West Bengal. In addition to his academic pursuits, he writes on a wide array of subjects encompassing literature, philosophy, religion, culture, cinema, politics, and the environment.