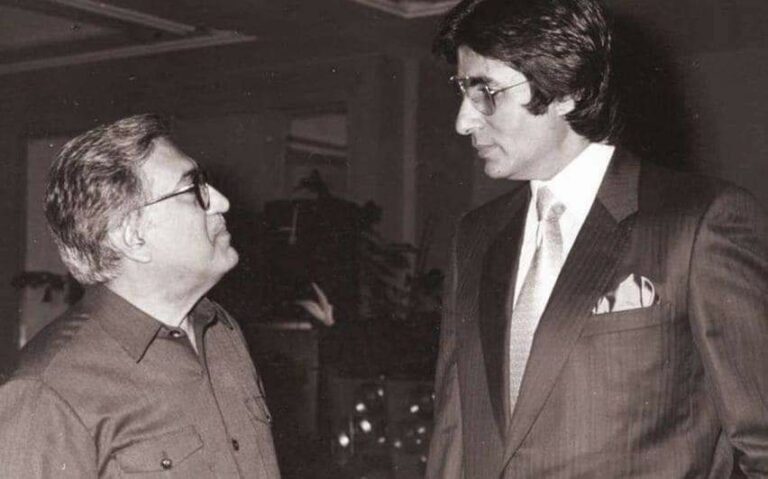

I found this last photo with the one and only legendary radio-man Ameen Sayani — taken by his son at the NCPA, Mumbai, in 2019, where I had gone to deliver the Bhaba Memorial Talk on Indian culture.

We knew each other well from the time I headed All India Radio and Doordarshan, as CEO, Prasar Bharati. I was his great admirer. During my public talk, I pointed to Ameen Sayani in the audience and mentioning why I considered him not just as a fascinating entertainer — India’s first radio jockey — but as someone who made a great, but unrecognised contribution in the unification of India. I explained that, by popularising Hindi film music on radio throughout the diverse and often-conflicting subcontinent, he helped in creating a common mass medium that everyone understood and loved — across a vast multilingual India.

The entire hall of some 1500 people suddenly got up to clap, spontaneously, as a tribute to Ameen sahab. He, too, rose from his seat to acknowledge the gesture and to take a bow. He wiped his spectacles as his eyes may have been moist. After the talk, I went straight from the podium to his seat and he hugged me. He whispered that it was one of his finest hours. Ameen ji was 85 and I never imagined that this was the last time I would ever see him alive.

For those who do not know the full story— it began with his programme of introducing Hindi film music over ‘Radio Ceylon’ in August 1952. India had emerged as one nation from 14 British Indian provinces and 565 kingdoms — different princely states only five years earlier.

Physically it was united, amidst partition riots and inter-regional conflicts — but had neither a common language nor emotional unity. People spoke in hundreds of different languages, for English was only the language of the educated. But different regions resisted the imposition of strict Sanskritic Hindi as the national language. This was also the time when the Indian government had wanted people to listen only to high-brow classical music and ghazals. India’s first Information and Broadcasting Minister BV Keskar branded Hindi film music as low-class ‘laralappa’ and banned (yes, banned) Hindi film music over the monopoly radio network, All India Radio.

Paradoxically, this was also the golden era of Bollywood, when its haunting music and exquisite lyrics and songs enraptured everyone. The masses were, therefore, thirsty for such popular music — despite its ban over radio. Only a minuscule had expensive gramophones and very few could afford to go to cinema halls.

In 1952, a Swiss company called CIBA, selling Binaca toothpaste, decided to sponsor a Hindi film music programme over Radio Ceylon, with Ameen Sayani as the ‘jockey’. It was called ‘Binaca Geetmala’ and soon became a superhit parade of popular songs — with Ameen Sayani’s outstanding introductions and interventions. He told me one day, 60 years later, while chatting in his little studio in Colaba, how he recorded each week’s show in Bombay itself, and how the spool was dispatched to Colombo. It was broadcast from 8 pm to 9 pm every Wednesday.

Since Ceylon’s British war-time transmitters were very powerful — they were meant to reach war-time Southeast Asia — ‘Binaca Geetmala’ could be heard in most parts of India. It was so legendary that people stopped everything on Wednesday evenings to listen — and, in the process, imbibe the easy Hindustani language, that was peppered with Urdu romantic words and colloquialism.

But BV Keskar and the mighty Akashvani refused to acknowledge the voice of the people —while Sayani’s popularity soared to dizzy heights. After 5 years of public criticism and résistance, however, All India Radio capitulated and began its only popular film music channel called Vividh Bharati in 1957 — on the lines of Ameen ji. With its huge network and talented staff artistes and singers — many of who were from Bollywood — Akashvani’s Vividh Bharati service played an ever better and more comprehensive role in uniting the entire country in one single voice. Vividh Bharati’s iconic programmes like ‘Hawa Mahal’, ‘Jaimala’, ‘Aapki Farmaish’, ‘Bhoole Bisre Geet’, ‘Chitralok’, ‘Chayageet’ and the lot enraptured Indians — whether they liked ‘Kitabi’ Hindi or not. They joined audiences from obscure Jhumritalaiyah to better known metros in one emotional family — more so, when transistors spread radio like wildfire in the 1960s and the cassette mania took over thereafter.

What about Sayani? His later ‘Colgate Cibaca Sangeetmala’ ran from 1954 to 1994 on Radio Ceylon and then he started doing programmes for Vividh Bharati — reaching out to more Indians and bonding them. He recorded some 50,000 radio programmes, lent his voice to 19,000 jingles, hosted TV shows, and did voiceovers and cameos in some Bollywood films — but his role as one who brought emotional unity among Indians is unforgettable.

All images: Google, YouTube

Jawhar Sircar is a former Member of Parliament. He retired from the Indian Administrative Service as India’s Culture Secy and was later Chief Executive Officer of the public broadcaster, Prasar Bharati. He is well-known for his articles on history, culture and politics and his columns appear in several leading Indian and foreign newspapers and magazines in English and Bengali. Sircar has also been the Chairman of the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata.