The first Prime Minister of India is often referred as the ‘architect of modern India.’ Interestingly, when India became a Sovereign state on 15th August 1947, it had nearly 330 million citizens. Among them there were only about 300 qualified architects. And it was those handful architects who with help from a few Western masters and specialists set India on the course of industrial and scientific development. It was an interesting time. We were nearly halfway into the century. The Second World War had just ended and the world was rebuilding itself from scratch. Nehru realized and articulated that the infrastructure and industrial projects of India were to become the temples of this nation. India was therefore, a land of opportunity. On the country’s 75th Independence Day let us take a look at some of the modern architects of India who laid the foundation of a nascent nation.

Habib Rahman and ‘Modern’ Architecture

Back then Indian Institute of Architects in Bombay (Mumbai) was the only formal training institution for architects. Few others, who could afford to study abroad, mostly got their degrees from the USA. The institute in Bombay was expectedly still very much under a British influence. On the contrary, the first batch of architects who studied in the US was free from any such stylistic influence. One of them was Habib Rahman. Rahman studied architecture at the MIT, Boston. He studied under some of the greatest exponents of the Bauhaus movement — Walter Gropius, the German architect who founded the Bauhaus school. Lawrence B. Anderson and William Wurster were also among his teachers. After a short stint at Gropius’ firm, Rahman returned to India in 1946.

Back in his hometown Calcutta, he joined the West Bengal Public Works Department better known as PWD as a senior architect. His first major project was the Gandhi Ghat, a memorial for Gandhi located in Barrackpore. It was a modernist concrete structure inaugurated by Jawaharlal Nehru in 1949. According to his son Ram Rahman, “Nehru loved the memorial and asked to meet the architect. He felt Rahman had succeeded in creating a structure that evoked the broader project of creating a new, modern nation also steeped in ancient tradition. On learning his background, Nehru said he would arrange for Rahman’s transfer to the Central Public Works Department (CPWD) in Delhi, as architects were desperately needed in the capital. He eventually moved there in 1953.”

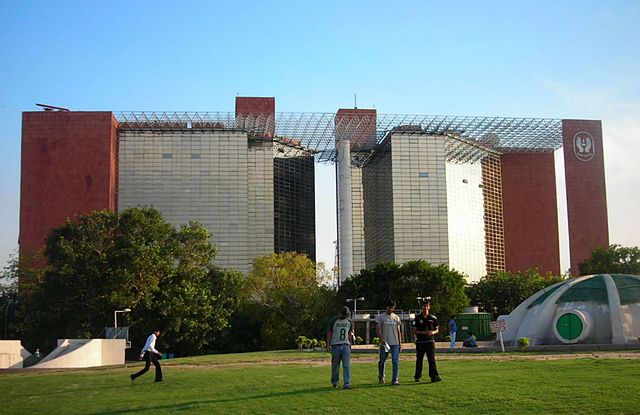

But before moving to Delhi Habib Rahman completed 80 projects in Bengal. Among them the New Secretariat Building, the Engineering College building in Shibpore and Hindu School building. In Delhi he designed some of the prominent administrative buildings like the UGC Office, The Comptroller and Auditor General Building and the Director of Post and Telegraph Office and the Rabindra Bhavan. He was the first architect to be awarded the Padma Shri and Padma Bhushan awards.

The Towering Influence of Le Corbusier

When Rahman was engaged in realizing the vision of new India in Delhi, the pioneer of modern architecture Le Corbusier was busy planning Chandigarh, the new capital of Punjab. Nehru had engaged the French architect who was considered the God of urban planning to build Chandigarh from ground up. Corbusier introduced a completely new style in urban planning and architecture. The new generation of architects was quick to identify a new intellectual dimension in his designs and was greatly influenced by his style. This generation sometime referred as the ‘post-Chandigarh generation’ of architects has been significant in shaping the modern architecture of India. One of his noteworthy disciples was B. V. Doshi. The other is Charles Correa. But we’ll come to Correa later.

Doshi is hailed as a living legend who was awarded the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2018. Doshi worked with Corbusier on his projects in Paris and Ahmedabad before establishing his own studio in 1955. He worked closely with another legendary architect Louis Kahn on the design of IIM, Ahmedabad. While Doshi is considered one of the pioneers of modernist and brutalist architecture in India he is also one of the most important teachers of the subject. In the 1960s B. V. Doshi established the Ahmedabad School of Architecture which he led for 50 years.

Among his notable works are the IIM, Bangalore, IIM Udaipur, Amdavad Ni Gufa and NIFT Delhi. He is considered to be an important proponent of low cost community housing and building academic institutions. According to the Pritzker Prize Jury, “Doshi is acutely aware of the context in which his buildings are located. His solutions take into account the social, environmental and economic dimensions, and therefore his architecture is totally engaged with sustainability.” Like Rahman B. V. Doshi was also awarded the Padma Shri and Padma Bhushan.

Fusing Indian and Western styles

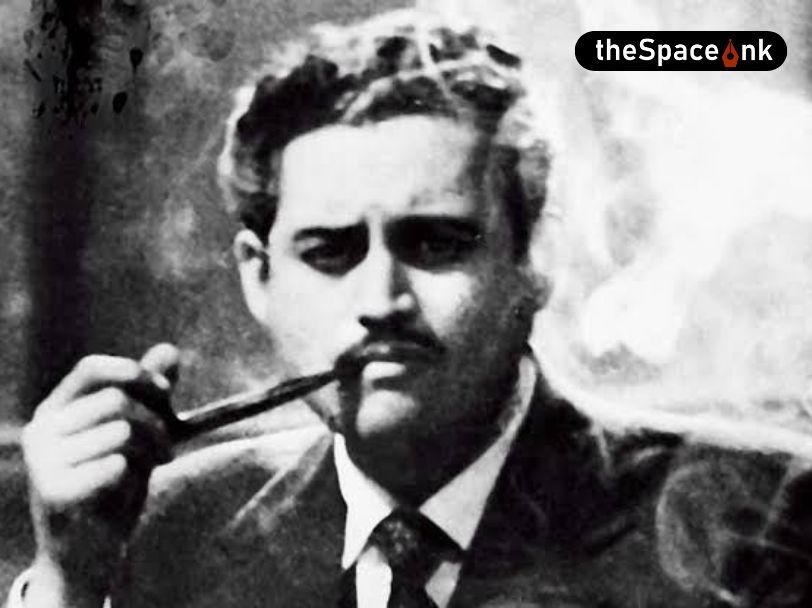

Charles Mark Correa returned to India and established his own practice in 1958 after obtaining his master’s degree from MIT. His first major project was the Mahatma Gandhi Memorial in Sabarmati Ashram, Ahmedabad. More projects followed. The Legislative Assembly of Madhya Pradesh, National Crafts Museum in New Delhi, Jawahar Kala Kendra in Jaipur and so on. Charles Correa’s use of courtyards, terraces and open spaces often segregated into different levels brings in a fusion of contemporary and classical styles. His sensibility as a planner and designer has managed to create a style that is reflective of the Indian societal structures.

British architect David Adjaye feels, “His work is the physical manifestation of the idea of Indian nationhood, modernity and progress. His vision sits at the nexus defining the contemporary Indian sensibility and it articulates a new Indian identity with a language that has a global resonance. He is someone who has that rare capacity to give physical form to something as intangible as ‘culture’ or ‘society’ – and his work is therefore critical: aesthetically; sociologically; and culturally.”

Correa’s body of work is extensive and demonstrates great variety of style. From the high-rise LIC office in New Delhi to the low cost housing in Belapur, he has done it all. Most importantly, he was able to look at architecture as an integrated part of society, culture and traditions and not exclusive of it.

Breaking the Mould

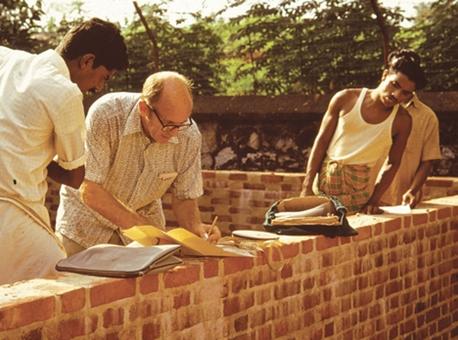

We had started our journey into the past with an architect whose first project was a memorial dedicated to Gandhi. We’ll end it with a British man who was inspired by Gandhi to create affordable and sustainable housing for the lower middle-class and poor. That man is Laurie Baker— the man who hates concrete and steel, loves mud and brick. Baker was first introduced to traditional rural housing in the foothills of Himalaya where he was building treatment centres for lepers. Later, he moved to Kerala, his wife’s native state. He was greatly inspired by Gandhi’s belief that all buildings should be constructed out of materials that can be found within a five mile radius.

He built the Centre for Development Studies in Thiruvananthapuram at nearly half the cost of similar Indian university buildings. He is a great lover of exposed brick and lime. Adam Hochschild writes, “When building the Centre for Development Studies, he made lime on the spot. He sent people to gather bullock-cartloads of seashells on beaches a few miles away, then had them baked in a mud kiln (its fan powered by someone pedaling a stationary bicycle) and ground up. Few of the scholars from India and abroad at the Centre realize that their office walls are partly held up by clamshells.”

Laurie Baker’s ideas have caught the imagination of a bunch of younger, environmentally aware Indian architects and engineers. Quite a few of them now work for COSTFORD, or the Centre of Science and Technology for Rural Development. This nonprofit organization practices Baker’s approach and designs homes for the poor.

A Long Way

We’ve come a long way from the days of the post-Independence euphoria. Many of the structures designed by the past masters have been flattened to the ground to make way for contemporary developments. Newer techniques and design philosophies continue to emerge from India’s growing need for sustainable and efficient infrastructure. But much of the India as we know it today came from the drawing boards of the past masters whose creative genius and studied determination shaped the country’s skyline.

Images courtesy: Sanjeet Choudhury, Wikimedia Commons, Facebook

Sources:

- The Brick Master of Kerala, Adam Hochschild

- https://thearchiblog.com/

- https://theculturetrip.com/

- https://www.dezeen.com/

- https://core.ac.uk/

- http://www.bauhaus-imaginista.org/

- https://archinect.com/

Thespaceink is particularly thankful to Sanjeet Choudhury for his help in the research for this article and Jnana-Pravaha Varanasi.

A cynic and an atheist who was raised in an old orthodox town by the river Hooghly, some 40 km from Kolkata. Pallavi eventually took up English literature and completed her studies from the Jadavpur University. Her lifestyle is largely determined by her toddler son and her taste buds. She has few friends. Milan Kundera, music and cinema are some of them.

One Response

One should visit Auroville, Pondicherry , India to experience the marvel of architecture