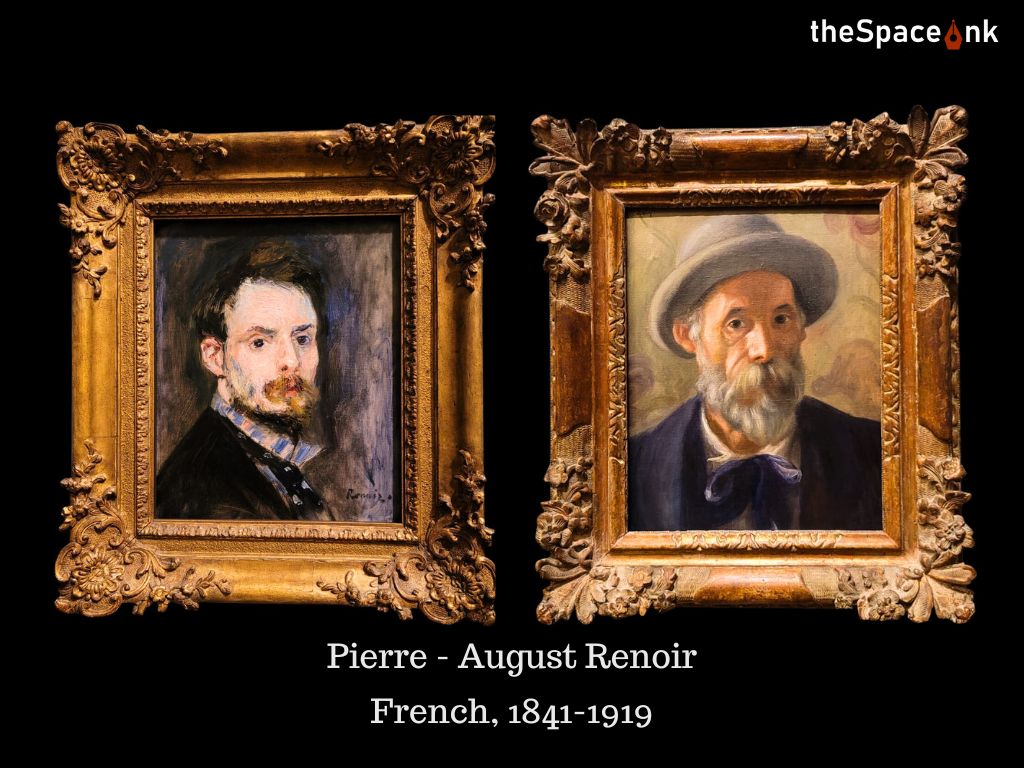

There’s something about returning to the same painting that changes how you see it. Since 2022, when we got a place near Williamstown, I’ve visited the Clark Art Institute more times than I can count. And every single time, I find myself standing before two Renoir self-portraits, separated by nearly a quarter-century, feeling like I’m discovering them all over again.

I’ve seen Renoirs in Paris, New York, Chicago, Boston—all the places you’d expect to find great Impressionist art. But finding these two intimate portraits in a small Massachusetts museum, tucked away in the Berkshires where most tourists never venture, felt different. It felt like stumbling onto a secret.

Also Read: A Life Well-Lived: Alice Munro (1931-2024)

The Journey to Get There

The Clark isn’t easy to reach, and that’s part of its magic. You don’t accidentally end up in Williamstown. The winding drive through rural Massachusetts requires intention, a deliberate choice to seek out art in an unlikely place. The visitors here aren’t killing time between other attractions—they’re genuine art lovers, artists, students, professors bringing their classes to see works they can’t find anywhere else.

When Sterling and Francine Clark built this museum in the 1950s, they chose this remote location deliberately. With Cold War anxieties rising and nuclear threats looming, they worried about keeping their precious collection safe from potential attacks on major cities. So they brought their treasures here, to this peaceful college town, opening the museum to the public in 1955. Sterling Clark had acquired thirty-eight Renoir works over thirty-five years, calling him “a great master” in his diary. That passionate collecting brought these two self-portraits together in this unlikely place.

The Young Artist: 1875

The first portrait shows Renoir at thirty-four, struggling to make ends meet, his paintings bringing in almost nothing. Yet look at how he presents himself—wild hair and untamed beard, yes, but wearing a crisp striped shirt and dark blue necktie. It’s the uniform of bohemian dignity: acknowledging poverty while refusing to surrender self-respect.

The painting itself is revolutionary. You can see him experimenting right there on the canvas, testing techniques that would later make him famous. The paint varies from nearly transparent to thickly layered, each brushstroke a small act of discovery. When this work appeared at the second Impressionist exhibition in 1876, Impressionism was still considered radical, even ridiculous. Renoir was betting everything on a vision few people understood.

What moves me is knowing this painting found an early champion. Dr. Georges de Bellio, an important collector, had “gone crazy” for it, according to Renoir. That single enthusiast’s support must have meant everything to a young artist wondering if anyone would ever understand what he was trying to do. The painting eventually made its way through Parisian dealers until 1939, when Sterling Clark bought it—beating his own brother Stephen to the purchase. Sterling relished that small victory.

What strikes me most is the honesty. Renoir could have painted himself as he wished to be remembered—heroic, triumphant, eternally youthful. Instead, he gave us truth. The 1875 portrait shows the struggling artist with fierce determination, still seeking validation. The 1899 portrait reveals the aging master with unflinching clarity about what was coming—kept private for decades, perhaps too personal to share.

The Established Master: 1899

Twenty-four years later, everything had changed. By 1899, at fifty-eight, Renoir had achieved recognition and financial security. The self-portrait from this year shows a well-groomed gentleman in fine clothing, with flowered wallpaper suggesting domestic comfort. The wild bohemian had become prosperous bourgeois.

But look closer at his eyes. There’s a searching quality, an intense scrutiny that speaks of something harder than poverty: physical suffering. In 1899, rheumatoid arthritis was beginning its attack on his body, a twenty-year battle that would eventually deform his hands and make every brushstroke an act of will.

Here’s what haunts me most about this portrait: Renoir never exhibited it, and it remained in his studio until his death twenty years later. For two decades, this painting hung in his private space—some accounts suggest it was in his bedroom—a daily reminder of who he had been and who he was becoming. This wasn’t painted for the world. It was a private reckoning, a conversation with himself captured in paint.

Also Read: Woodland Still Life: Discovering Abraham Mignon of the Golden Dutch Era

The painting wasn’t seen publicly until 1935, sixteen years after Renoir’s death, when it appeared in an exhibition in London. By then, it had passed to his son Pierre, who eventually consigned it to the renowned Durand-Ruel gallery. The gallery transferred it to their New York branch in 1936, and Sterling Clark purchased it on April 10, 1937.

Think about that journey: from Renoir’s bedroom to a London exhibition to New York dealers, and finally to this quiet Massachusetts museum where it would remain, reunited with the portrait of the young man Renoir once was.

What They Tell Me

I’ve spent years with these paintings now, and they’ve taught me something the grand museums never could. In the Musée d’Orsay or the Met, you’re swept along in crowds, catching glimpses of masterpieces between other people’s heads. Here, I can stand as long as I want, return whenever I need to, let these works settle into my understanding slowly.

The fact that both portraits survived their separate journeys—one sold and celebrated early, the other hidden away until after the artist’s death—and ended up together in Williamstown through Sterling Clark’s obsessive passion feels almost miraculous. Clark’s first Renoir purchase was in 1916, and over the next three decades, he built what would become one of the finest collections anywhere.

Together, these two faces tell a story about what it means to persist in creative work. The young Renoir was hungry, experimental, using his own face as a testing ground for revolution. He was fighting to be seen, to prove Impressionism wasn’t just a fad but a legitimate artistic vision.

The older Renoir had won that fight. He’d achieved everything the younger man could have hoped for—success, security, a place in art history. But he’d also learned what all artists eventually learn: that success doesn’t protect you from suffering, that bodies fail even when vision remains clear.

When asked why he kept painting through the pain of arthritis in his advanced years, Renoir replied, “The pain passes, but the beauty remains.” That determination—that absolute refusal to let physical suffering silence his artistic voice—is written all over his face in the 1899 work. (Clark)

A Personal Revelation

The revelation for me wasn’t just seeing these paintings, but seeing them here, in this unexpected place, where I could return to them again and again. Each visit reveals something new—a subtle play of light I hadn’t noticed, an emotional resonance I’d missed, a technical detail that suddenly makes sense.

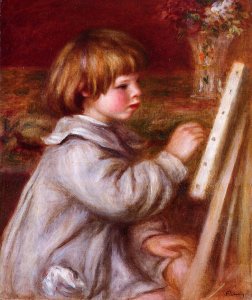

These aren’t the Renoirs most people know. They’re not the sun-dappled garden parties or rosy-cheeked children. They’re something more intimate: an artist’s honest conversation with himself across twenty-four years. A young man betting everything on his talent. An older man confronting mortality while refusing to stop creating. (Clark)

Standing before them again and again since 2022, I’ve come to see these portraits not just as art history, but as companions. They’ve witnessed my own small transformations over these years, silently offering their lesson: keep working, keep seeing, keep creating. The pain passes, but the beauty remains.

What strikes me most is the honesty. Renoir could have painted himself as he wished to be remembered—heroic, triumphant, eternally youthful. Instead, he gave us truth. The 1875 portrait shows the struggling artist with fierce determination, still seeking validation. The 1899 portrait reveals the aging master with unflinching clarity about what was coming—kept private for decades, perhaps too personal to share. (Clark)

The fact that both portraits survived their separate journeys—one sold and celebrated early, the other hidden away until after the artist’s death—and ended up together in Williamstown through Sterling Clark’s obsessive passion feels almost miraculous. Clark’s first Renoir purchase was in 1916, and over the next three decades, he built what would become one of the finest collections anywhere. His decision to keep it here, safe from the world’s chaos, means that those of us lucky enough to live nearby can visit regularly, can let these paintings become part of our interior landscape.

Every time I leave the Clark and drive home through the winding Massachusetts roads, I carry these two faces with me. The young artist who believed in himself when few others did. The established master who kept painting through pain because beauty mattered more than comfort, who looked at himself honestly in 1899 and painted what he saw, keeping that vulnerability private until the world was ready to see it.

Standing before them again and again since 2022, I’ve come to see these portraits not just as art history, but as companions. They’ve witnessed my own small transformations over these years, silently offering their lesson: keep working, keep seeing, keep creating. The pain passes, but the beauty remains. (Clark)

To Visit: https://www.clarkart.edu/

Image Courtesy: Mousumi Duttaray (Author), Pierre Auguste Renoir

All Rights Reserved

Mousumi was raised in Kolkata but now call New York her home. She pursued her PhD from Indiana University Bloomington and currently works as a Marketing & Consumer Data and Design Analytics professional. She is Co-founder and Director at MDRK Partners. She loves to read, cook, take photos on her phone and travel.