Stories of detection enthrall us. We as readers love the palpable excitement of solving a mind-boggling mystery, and long for the tantalising thrill of suspense that a fictional crime investigation brings to the table. Adrenaline bubbles inside us while turning the pages, trying eagerly to deduce the identity of the criminal before the sleuth’s big reveal. Every plot twist, every red herring gets our nerve endings tingling. With bated breath we wait for the denouement, and more often than not are aptly rewarded with a healthy dose of surprise at the end.

the pipe-smoking, deerstalker-wearing protagonist cleverer than half the population of the city combined, more adept at the art of deduction than any ordinary person can ever dream of becoming, and idiosyncratic to boot

Ardent fans of crime fiction have always been enamored by the archetypal detective hero—the pipe-smoking, deerstalker-wearing protagonist cleverer than half the population of the city combined, more adept at the art of deduction than any ordinary person can ever dream of becoming, and idiosyncratic to boot. Even his simpleton but loyal sidekick appeals to us greatly, as in most instances it is he who narrates the tale; it is through his eyes we watch the drama unfold. And nothing gives us more joy than seeing the sleuth outwit the criminal in the final showdown. The crisis is resolved, the wrongdoer gets his comeuppance, and the reader finds comfort in the triumph of justice. Yet there are also times when we root for the charismatic bad guy, cheer an ingenious felon on just for the fun of it. That is why law-defying anti-heroes like the gentleman thief Arsene Lupin and the amateur cracksman A. J. Raffles easily lay claim to our hearts; even outright villains such as Professor Moriarty walk off into the sunset having earned our respect.

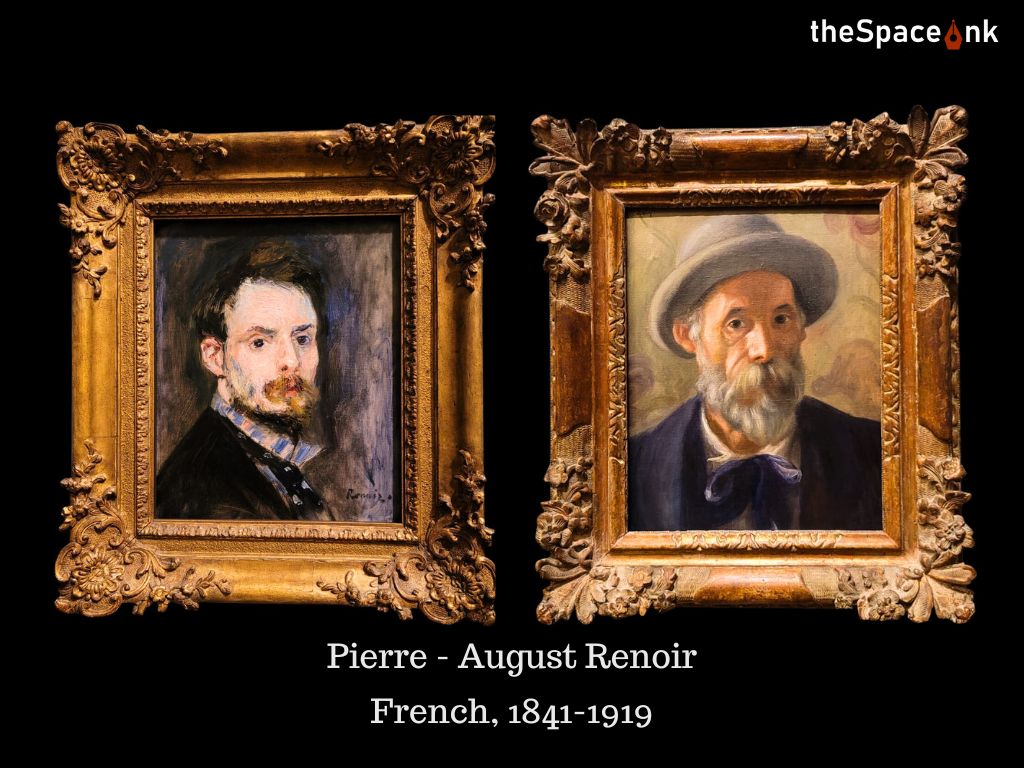

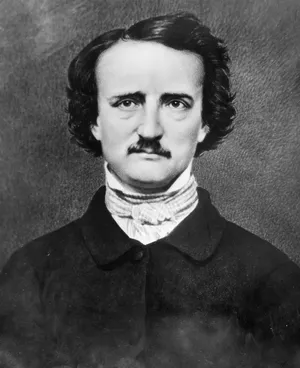

Some researchers cite Voltaire’s Zadig (1748) as the earliest example of Western detective fiction. There are also those who argue in favor of E.T.A. Hoffman’s Mademoiselle de Scuderi (1819) or Steen Steensen Bilcher’s The Rector of Veilbye (1829). But most modern-day critics agree that the genre had its genesis at the hands of the American polymath Edgar Allan Poe. In The Murders at Rue Morgue (1841), Poe created the unforgettable character of C. Auguste Dupin—an eccentric but brilliant investigator who solves a perplexing double homicide relying solely on his prowess of ‘ratiocination’—a form of logic-based reasoning. Two more stories centering on Dupin—The Mystery of Marie Roget and The Purloined Letter—followed, and the three tales together helped establish a “plot formula that has been successful ever since.”

Emile Gaboriau pioneered the genre in France in the 1860s; his L’Affaire Lerouge (1866) is still widely recognized as the first-ever full-length detective novel. In the same decade, Wilkie Collins wrote The Moonstone, which T. S. Elliot praised as “the first, the longest and the best of modern English detective novels.” The 1870s witnessed Anna Katharine Green popularize the field among the middle-class, and develop the notion of the recurring detective. Then in 1887, Arthur Conan Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet appeared in Beeton’s Christmas Annual magazine, introducing a new sleuth by the name of Sherlock Holmes.

The tall, lean, hawk-nosed consulting detective of Baker Street readily established himself as the doyen of all crime solvers. Armed with superlative observational skills and a profound knowledge of criminology

The tall, lean, hawk-nosed consulting detective of Baker Street readily established himself as the doyen of all crime solvers. Armed with superlative observational skills and a profound knowledge of criminology, Holmes could positively identify an unknown perpetrator from the minutest of clues left behind at the crime scene—a partial footprint, or a fleck of cigar ash. Discombobulating his first-time clients by merely glancing at them and divulging particulars about their lives was his favourite pastime, and cracking cases far beyond the grasp of Scotland Yard’s finest was to him a walk in the park. Doyle wrote a total of 60 tales chronicling the exploits of Holmes—four of them novels, the rest short stories—and each and every one of them is considered a gem today.

The initial years of the twentieth century gave the readers three fictional detectives of note—Richard Austin Freeman’s erudite forensic investigator Dr. Thorndyke, Ernest Bramah’s visually impaired but otherwise remarkable Max Carrados, and G. K. Chesterton’s mild-mannered parish priest Father Brown. A number of Freeman’s tales featuring Dr. Thorndyke were of the ‘inverted detective story’ variety—“crime fiction in which the commission of the crime is described at the beginning, usually including the identity of the perpetrator, with the story then describing the detective’s attempt to solve the mystery”—and caused quite a stir among the readers of conventional ‘whodunits’.

Bramah was no straggler either; Max Carrados’ popularity was once believed to rival that of Holmes, and George Orwell’s observation that, along with Doyle’s and Freeman’s oeuvres, Bramah’s Carrados mysteries “are the only detective stories since Poe that are worth re-reading”, speaks volumes about the case-solving abilities of the blind private eye (pun intended). Chesterton’s homily-spouting amateur detective, Father Brown, was by far the most unusual of the lot. His deep understanding of the human psyche, coupled with an innate compassion for lost souls, made him the perfect seeker of truth—someone who not only brought the criminals to the book but also guided them towards the path of God and redemption.

‘The Golden Age of Detective Fiction’ (predominantly the 1920s and ‘30s) saw multiple illustrious sleuths grace the pages of mystery novels; the majority of them creative brain-children of the vaunted ‘Queen of Crime’ Agatha Christie. Picturesque country locales, exotic excavation sites, luxury yachts, transcontinental trains, even the interior of a flying Aeroplane—there was not a place under the sun where she did not conceive of a murder, and her investigators, upon whom the onus of solving the homicides generally rested, came in all kinds—the quirky foreigner obsessed with method and order (Hercule Poirot), the elderly village spinster with a keen eye for details (Miss Marple), the young couple ever eager to dash into the mouth of danger (Tommy and Tuppence), the retired government employee turned ‘detective of the heart’ (Parker Pyne), and the astute observer of life seeking inspiration from the personification of Death himself (Mr. Satterthwaite).

Au contraire, Dorothy L. Sayers—Christie’s contemporary, and a prominent practitioner of the craft in her own right—was more of a one-detective author. Sophisticated in her approach to penning ‘whodunits’, and caring more about sketching well-realised characters than regaling the readers with the flashy stuff, she portrayed her detective, Lord Peter Wimsey, as the quintessential British aristocrat with a flair for intuition. An amateur cricketer, a war veteran, a collector of old books and a connoisseur of food and music—Lord Peter was a man of many parts, and made judicious use of his talents to wrap up the toughest of cases.

John Dickson Carr, who also wrote under the pen names Carter Dickson and Carr Dickson, was another towering wordsmith of the ‘Golden Age’, his renown firmly cemented by complex, plot-driven stories that relied heavily on intricate puzzles and contraptions. Apart from being the undisputed master of ‘Locked Room Mysteries’ (a subgenre of crime fiction centred on seemingly impossible crimes), Carr was also an avid Sherlockian, and along with Adrian Conan Doyle, penned several engaging Holmes pastiches. Dr. Gideon Fell and Henry Merrivale were two of his best-known detectives, with the former garnering praise from the famed novelist Kingsley Amis (who acknowledged Dr. Fell as “one of the three great successors to Sherlock Holmes”), and the latter receiving laurels from the well-known critic and author of the seminal non-fiction volume Murder for Pleasure, Howard Haycraft.

During the late 1930s, the Western detective fiction scenario underwent a significant transformation as a bunch of new writers, embittered by the widespread vices afflicting society, and brimming with radical, even controversial ideas, began asserting their presence. Openly contemptuous of the contrived, at times silly nature of the crimes envisioned by their predecessors, they insisted on lending their works a grittier, more realistic tone. Thus the ‘hard-boiled’ variant of the genre emerged. Introduced by Dashiell Hammett, and ably nurtured by the likes of James M. Cain and Raymond Chandler, it soon became a staple for pulp magazines like Black Mask, Dime Detective and Detective Fiction Weekly. Hard-boiled tales—often nuanced mysteries generously laced with noiristic imagery, sleazy sex and graphic violence—caught the fancy of suspense aficionados big time, and soon became a sure-shot formula for blockbuster Hollywood flicks.

Nowadays, top-flight detective fiction writers lead the lives of celebrities, with major publishing houses happily paying them millions in royalties and catering to all their demands

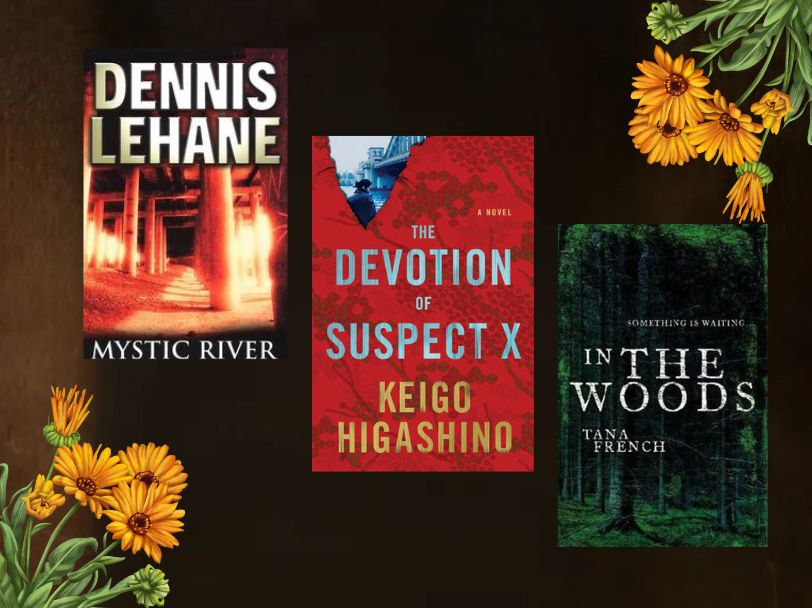

Since then, the field has grown too vast and convoluted to be properly defined, let alone categorized into neatly labeled boxes. Simultaneously, it has obliterated the ‘Penny Dreadful’ ghetto walls that had once kept it incarcerated, and conquered a large chunk of the lucrative popular-fiction market. Nowadays, top-flight detective fiction writers lead the lives of celebrities, with major publishing houses happily paying them millions in royalties and catering to all their demands. Every respectable bookstore allocates a shelf or two, if not an entire section, for crime and detective fiction; conventions like Bouchercon are attended by thousands of eager fans from all over the world. Even high-brow academicians have come to appreciate the value of detective fiction, thanks to genre-bending works such as Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose (1980), Dennis Lehane’s Mystic River (2001), Keigo Higashino’s The Devotion of Suspect X (2005) and Tana French’s In The Woods (2007).

It can, therefore, be said that the allure of well-crafted detective fiction will not wane anytime soon, but steadily intensify in the years to come. Nestled in the comfort of well-worn couches, readers will continue being enraptured by the art of intrigue, and lose themselves in tales where legendary sleuths unravel cryptic clues, apprehend elusive criminals, and uphold the banner of justice.

Image Courtesy:

- double9books.com

- britannica.com

- gutenberg.net

- oldtowncrier.com

- npg.org.

- biblio.com

- goodreads.com

- wikipedia.org

Souvik Chakraborty, by profession a mid-level manager at Steel Authority of India Ltd., has, since his early days, been a voracious reader of both literary and popular fiction. Till date he has edited eight acclaimed anthologies in English, and a handful in Bengali as well. When not busy collating stories, Souvik likes to try his hand at penning poems and speculative yarns, and over the past few years, has contributed a number of short pieces to various renowned periodicals. He loves playing the guitar, and his hobbies include listening to rock music and watching thriller movies.