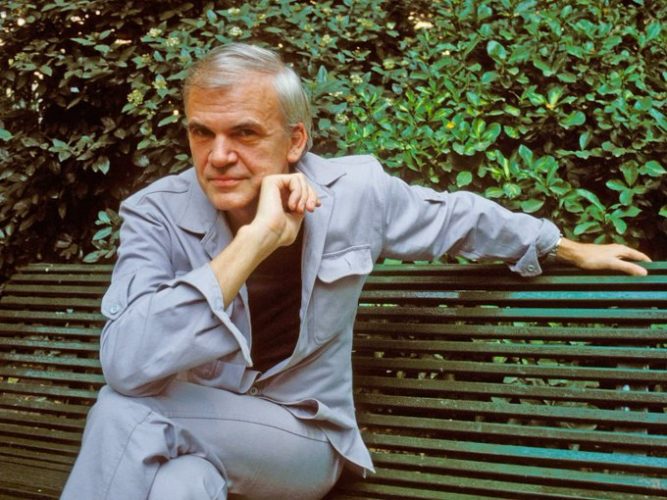

Born in Czechoslovakia in 1929, Milan Kundera found himself growing up in an important historical period when communism emerged as an alternative political and economic philosophy to Western democracy and capitalism between the 1920s and 1980.

Several countries in Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America embraced communism during this period. Under the leadership of the Soviet Union, officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), a confederation of 15 republics, these countries formed a coalition of communist countries that came to be known by names such as the Communist Bloc, the Socialist Bloc, the Soviet Bloc, or the Eastern Bloc. During the Cold War era between 1947 and 1991, trying to counterbalance the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the Communist Bloc played a significant role in shaping the geopolitical landscape of the world. It also contributed to escalating the rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union. The USSR, at the same time, maintained considerable control over the Communist Bloc politically and militarily.

After World War II, as Czechoslovakia came under the influence of the Soviet Union, by means of a successful coup in 1948, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (CPC) came to power and established a communist regime in the country. Czechoslovakia adopted a Soviet model of a communist economic programme, participated in trade agreements within the Communist Bloc and received economic assistance from the Soviet Union.

As a young man, Kundera joined the communist party of Czechoslovakia. However, soon he became critical of the communist regime and was expelled from the party for his anti-communist activities in 1950. Though he was readmitted to the party in 1956, he continued to be critical of the regime and used his favoured medium of expression, literature, as a vehicle for his critique.

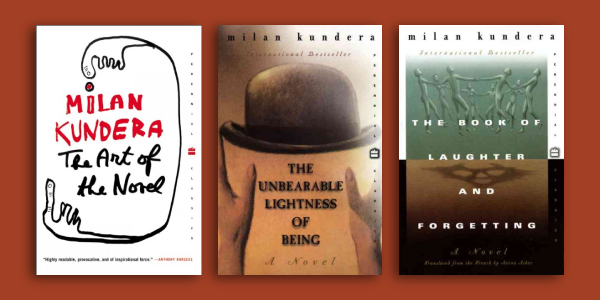

Set in the Soviet-controlled communist Czechoslovakia of the 1950s, his first novel, The Joke (1967), satirises the totalitarian communist regime of his country. It depicts Ludvik Jahn, a university student and member of the Communist Party, who writes a joke on a postcard for his girlfriend, Marketa. The joke says, “Optimism is the opium of the people! A healthy atmosphere stinks of stupidity! Long live Trotsky!”

The first statement in the joke, “Optimism is the opium of the people,” is an obvious play on Karl Marx’s statement, “Religion is the opium of the people.” Replacing ‘religion’ with ‘optimism,’ the joke suggests that optimism can function as a source of escape or distraction just the way religion can function as a source of escape and distraction from repressive socio-economic conditions.

The second statement, “A healthy atmosphere stinks of stupidity,” in ironic terms conveys that a supposedly perfect and harmonious environment stifles intellect and critical thinking by promoting conformity. Hence, it stinks of stupidity.

The third statement, “Long live Trotsky,” is a dissentious political slogan. Leon Trotsky was an important leader of the Russian Revolution who played a prominent role in the Soviet Union during its infancy. As he fell out of favour with Joseph Stalin, he was exiled and assassinated. The slogan expresses open dissent against the prevailing political regime and its ideology in agreement with the dissenter Trotsky’s ideology.

The guardians of the communist regime that cannot take a joke in their stride get furious; they come heavily down on Jahn by expelling him both from the party and the university. Thoroughly dejected and disillusioned with the communist regime, Jahn regards the unfortunate turn of events in his life related to the joke as the communist regime’s betrayal of him. Through his protagonist’s experience, Kundera depicts what it is to live under a totalitarian regime that permits no scope for freedom of expression and has no respect for individuality. The pivotal thematic point of the novel is the existential struggle of an individual trapped in a repressive system that raises questions regarding the nature of power, individual freedom, and search for meaning in life.

As a young man, Kundera joined the communist party of Czechoslovakia. However, soon he became critical of the communist regime and was expelled from the party for his anti-communist activities in 1950. Though he was readmitted to the party in 1956, he continued to be critical of the regime and used his favoured medium of expression, literature, as a vehicle for his critique.

Jahn’s joke is packed with subversive humour and criticism against the Czechoslovakian communist regime under the patronage of the Soviet Union. Through his joke, Kundera directs his critique against the relentless repressive communist regime of his country. The Joke is one of Kundera’s acclaimed novels and one of the seminal works of Czech literature.

When Alexander Dubcek was elected First Secretary of the CPC in 1968, in view of creating socialism with a human face, he initiated a short-lived reformation programme in the country in terms of decentralization of the economy, democratization of the political system, and greater freedom of speech which came to be known as Prague Spring. Kundera became an active proponent of the Prague Spring. Since the Prague Spring was a direct challenge to the Soviet model of communist orthodoxy of the time, with the support of other Warsaw Pact countries, the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia in August 1968, obliterated the Prague Spring and re-established the absolute sway of the Communist Bloc over the country. The Soviet-controlled Czechoslovakian government cracked down on nonconformists, purged the reformist elements from the Communist Party and instituted strict censorship. On account of being a prominent voice of the Prague Spring, Kundera was expelled from the Association of Writers in Czechoslovakia, his books were taken off the shelves of bookstores, and his plays were banned in theatres.

However, in 1969, he published his Life is Elsewhere, a novel that depicts the life of Jaromil, a young Czechoslovakian poet and a fictionalized version of Kundera. The narrative explores the trajectory of the protagonist’s life from his childhood to adulthood, tracing his romantic relationships, political engagements, and artistic pursuits. He is seen struggling with crucial alternatives such as his artistic ambitions and his relationships on one side and his personal freedom and his political conformity on another side. Through Jaromil, a romanticized image of the poet as a figure of rebellion, Kundera explores the consequences of idealism and the complexities of personal and political identity.

Kundera’s criticism of the Soviet invasion led to the banning of his books in the country. Subsequently, he was expelled from the communist party again for the second time in 1970. However, Kundera would not give up his critique of the system he could not reconcile with. He used his pen as his most potent weapon.

Setting his 1972 novel, The Farewell Party, a burlesque, in a rural mountain spa in an unnamed country, seemingly Czechoslovakia, Kundera tells the story of Klima, a jazz trumpeter who after having impregnated Ruzena, a nurse, tries to persuade her to get an abortion done. Blurring the boundary between truth and lies, the narrative shows how the characters in the novel, driven by different motives, interests, concerns and perspectives not only go about manipulating and deceiving others but also justify their actions. The narrative also exposes the oppression, corruption, and censorship that have become the strategy of the communist regime in the country and the violence, injustice and hypocrisy that have become a way of life in society.

Kundera’s criticism of the Soviet invasion led to the banning of his books in the country. Subsequently, he was expelled from the communist party again for the second time in 1970. However, Kundera would not give up his critique of the system he could not reconcile with. He used his pen as his most potent weapon.

Kundera relinquished his reformist ideals and went into exile in France in 1975. Based on his own experience of living under communist rule, in his 1979 novel, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1979), he presents his nuanced critique of the Soviet-controlled communist regime in Czechoslovakia and his disenchantment and frustration with the totalitarian regime. Through the personal tragedy and trauma of the character Tamia haunted by the memory of her late husband, Mirek, a high-ranking communist official who fell out of favour with the regime and disappeared, Kundera depicts the consequences of living under a repressive regime and explores the themes of loss, memory, love and grief.

Since the communist regime in Czechoslovakia considered The Book of Laughter and Forgetting politically subversive and hence detrimental to the communist regime, shortly after its publication, it was banned in Czechoslovakia and in other countries within the Communist Bloc. In spite of the ban, the novel enjoyed international attention and readership.

Because of his reformist political views and anti-communist stance, in 1979, Czechoslovakia revoked Kundera’s citizenship. France came to his rescue granting him citizenship in 1981.

In 1984, Kundera published his international bestseller and philosophical novel, The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Interweaving Czechoslovakian political and historical events, mainly the Prague Spring and the subsequent Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, the novel depicts a triangular love story. Unfolding the love story along the existentialist philosophical line, the narrative explores the concept of lightness and heaviness. Since human beings lack a predetermined trajectory, purpose, and meaning, they experience an existential lightness as a result of which they are free to make choices and decisions and find their subjective meaning. At the same time, they are driven by an existential heaviness, a desire for a fixed and predetermined trajectory, purpose, and meaning that takes away their burden of having to make decisions and choices.

Weaving multiple stories together and lacing them with reflections on art, love, life, existence and mortality, through his 1990 philosophical and introspective novel, Immortality, Kundera tries to examine the interplay between personal and historical memory as well as reflect on the meaning of life. Immortality was followed by Slowness (1995), Identity (1998), Ignorance (2000) and The Festival of Insignificance (2014).

From 1989 onwards the world witnessed unprecedented changes. The Revolutions of 1989 which encompassed a series of non-violent revolutions in various countries of Central and Eastern Europe brought about the collapse of the communist regimes in those countries paving the way for democracy. As part of these evolutions, in 1989, Czechoslovakia witnessed a peaceful revolution called Velvet Revolution that brought an end to the communist regime in the country initiating its transition to democracy. By 1991, the Cold War came to an end, and the Soviet Union collapsed. In 1993, Czechoslovakia was split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

The Czech translation of The Unbearable Lightness of Being was published first in 2006, and in 2008, while still a French citizen, for the novel, Kundera was given the Czech State Award for Literature, the highest literary honour in the Czech Republic. Though Kundera refused to attend the ceremony in Prague, he wrote to the minister of culture in the Czech Republic saying that was deeply moved by the recognition. He also expressed his gratitude to his Czech readers and publishers who stood by him while the iron hands of the communist regime struck him hard.

In recognition of Kundera’s contribution to Czech literature and culture, and as a sign of reconciliation between Kundera and his homeland, the Czech Republic granted him citizenship again in 2019. At the age of ninety, forty years after the revocation of his citizenship and life in exile, Kundera became a Czech citizen again. Andrej Babis, the Czech Prime Minister, personally handed him the citizenship certificate in Paris. Though Kundera accepted citizenship, he preferred to continue living in France.

In 2020, the Czech Republic honoured him with another recognition, the Franz Kafka Prize, a recognition given to writers whose work has exceptional artistic quality and humanistic character.

Talking about the question of returning to his homeland, Kundera told a German newspaper in 1984 “There is no such dream of a return, I took my Prague with me; the smell, the taste, the language, the landscape, the culture.” In the same year, he told The New York Times, “You have to ask: What is home? What does it mean to be at home? It’s a complicated question. I can honestly say that I feel much better here in Paris than I did in Prague, but then can I also say that I lost my home, leaving Prague? All I know is that before I left I was terrified of ‘losing home’ and that after I left I realised – it was with a certain astonishment – that I did not feel loss, I did not feel deprived.”

Kundera did not have to return to the Czech Republic to be at home. His experience in life taught him to redefine the concept of home. He was happy to be at home in exile, so he embraced death at home in exile on 11 July 2023 in Paris. A person like Kundera is a citizen not just of the country of his birth or adoption but of every country in the world because the influence and impact of Kundera is beyond any geographical confines. Beyond doubt, Kundera’s has been an inspiring saga of resistance, exile, recognition and reconciliation.

Sacaria Joseph is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at St. Xavier’s College, Kolkata. Having pursued his undergraduate studies at St. Xavier’s College, he furthered his academic journey by obtaining a Master of Arts degree in English Literature from Pune University, a Master of Philosophy from Jadavpur University, Kolkata, and a PhD from Visva-Bharati University, West Bengal. In addition to his academic pursuits, he writes on a wide array of subjects encompassing literature, philosophy, religion, culture, cinema, politics, and the environment.