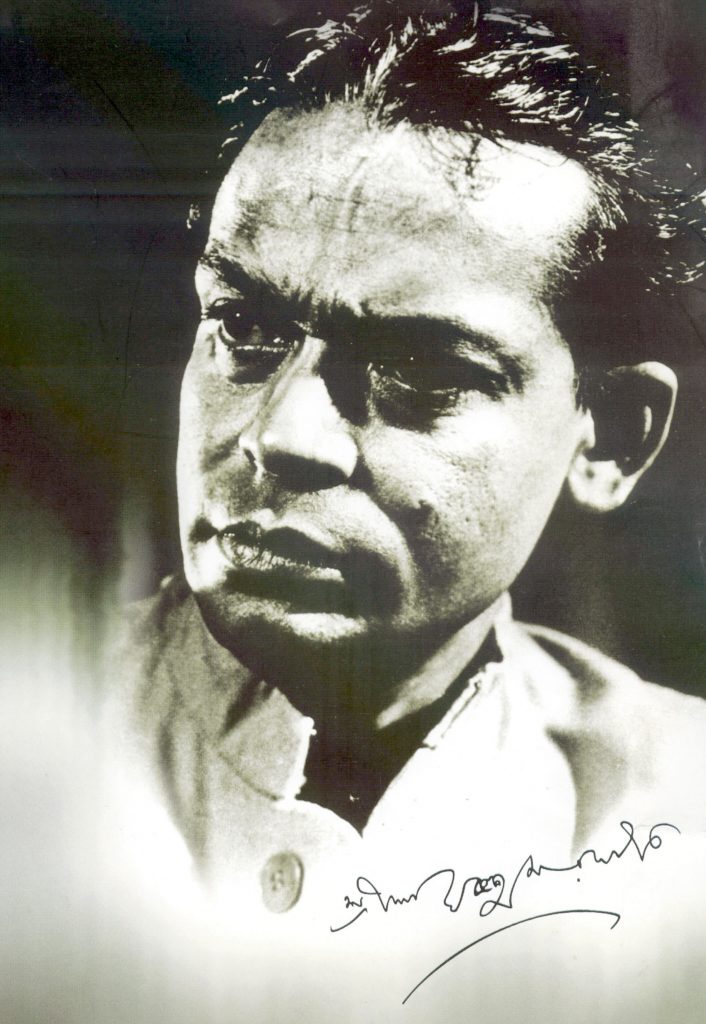

For the first time in Indian cinema, Ghatak showed that “the movie camera was not merely an obstructive eavesdropper but a commentator, philosopher, historian, critic and poet, not a peep-window into the lives of a group of characters but a testament – narrating, recalling, rejecting, accepting, questioning, protesting, losing and winning,” wrote Safdar Hashmi.

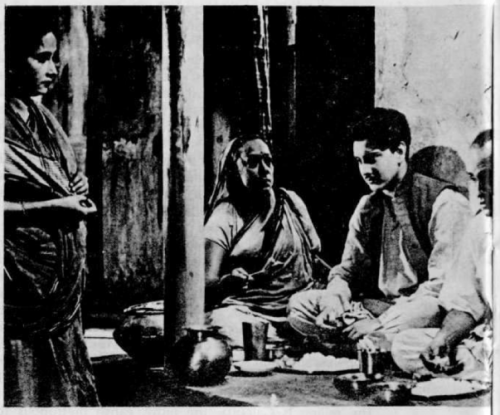

In many ways, Nagarik reflects some of the misgivings Ghatak felt when he first landed in Calcutta. Ghatak claimed that Nagarik was a political statement. It set out to analyse the agonies of a middle-class family of Calcutta engaged in a grim struggle for survival against oppressive social forces. It portrayed the slow and tragic descent of a middle-class family. This descent, several rungs down the hierarchical ladder of socio-economic class structure was geographic on the surface – the family moved home from one pocket of the city to a seamier and lower pocket. But beneath this surface, lay the decay in the lives of each member of the family. Their characters had metamorphosed to something quite different from what they were when the film opened.

The entire socio-economic base of the family changes over the unfolding of the film. This dynamism is shocking in its impact. He had the courage and the ability to face, interpret and present bitter truths with brutal frankness. Seen many years later, in 1982, Nagarik reminded this viewer of the whiplash Ghatak used in Meghe Dhaka Tara. While Meghe Dhaka Tara used the whiplash on the soundtrack, Nagarik, the film, was itself a whiplash inflicted on the audience, to shake it and wake it from its dream-filled slumber of illusion.

In Meghe Dhaka Tara, the city of Calcutta is both victimizer and victim. It is the victim of the changed geography of the state borders, truncated by Partition. And it is a victimizer of girls like Nita, forced into a trapped life by the Partition and the shift. Ghatak’s love for Calcutta, if ever he developed any, was possibly concentric – confined to some marginal pockets. His attention seems to repeatedly focus on the marginal fringes of a Calcutta most of us have never known. It is shorn of the chintzy chutzpah and glamour big metros are famous for. The narrative unfolds against the backdrop of the refugee colonies concentrated in Jadavpur, Netajinagar and Bijoygarh.

The single leitmotif of a torn slipper, repeated just once, is Ghatak’s strong indictment on Calcutta. Calcutta, he seems to say through the film, sustains the vicious circle of poverty and social injustice almost with a vengeance. Nita’s death, in this sense, is not a moral lesson from Calcutta to its massive refugee population. Rather, it is a sustained threat, a warning that leaves no option but to wear a pervasive, real and violent face. Nita forms a tiny microcosm of the thousands of girls whose families migrated to the refugee colonies of Kolkata and took up tuitions or low-paid jobs or both to keep the last embers of the family fires burning. This was based on a novel by Ramapada Choudhury.

Calcutta wears a different face in Subarnarekha that opens with the foundation of Naba Jiban Colony, a colony for refugees in Calcutta. This comes across in the way Haraprasad describes the city to his friend Ishwar as a way of consoling him for the sudden disappearance of his sister. “This is the city of fun if you have money to buy it,” he says. Ghatak then exposes us to a Calcutta many of us have never seen. It is a Calcutta of horseracing turfs and gambling dens, of brothels and bars. A city where affluence is synonymous to heartlessness and casual indifference to fellow-beings. Haraprasad says, “You have money, I have none. There is real fun in Calcutta now – in the hotels, restaurants, racing turfs – what deadly fun!” His use of ‘deadly’ before ‘fun’ is a subtle irony; so subtle that you almost miss it. The story zeroes in on the theme of uprooting – geographic, emotional, moral and for Sita, even political. The storyline is deceptively simple on the surface. The film sends a series of electric shocks down the spine of a growingly disturbed audience. “Disturbance” aptly describes one’s reactions to Ghatak’s Subarnarekha.

In this film, Calcutta reduces in one instant, a principled man like Ishwar to a man in search of hedonistic pleasures, to a man seeking the ‘deadly fun’ his friend promised inside a brothel. Calcutta is no less cruel to Sita, because it turns her name into the tragic irony of her life. When Sita slaughters herself after seeing who her ‘client’ is, hers is more of a physical suicide than a moral one. For Ishwar however, the suicide is moral, yet, partly physical because with Sita’s death, a part of Ishwar dies along with her. Nor does Calcutta permit Sita the right and the freedom to live up to her name. She is no one’s wife, or daughter, or sister. Even her sisterhood is snatched away from her – a reality she fails to grope with.

If a bit of Ishwar dies with his sister, he also begins to live again. Calcutta offers him a lifeline after having taken it away. This comes in the shape of Sita’s little son Binu, who pulls Ishwar along because his steps are now hesitant. The roles of the guardian and his ward are reversed. It is now the little Binu who guides his ageing uncle Ishwar into a future of hope, if not happiness.

In this film, Calcutta reduces in one instant, a principled man like Ishwar to a man in search of hedonistic pleasures, to a man seeking the ‘deadly fun’ his friend promised inside a brothel. Calcutta is no less cruel to Sita, because it turns her name into the tragic irony of her life.

In Bari Theke Paliye, a young boy Kanchan, runs away from his village home to a large city. Though the city remains unnamed, we see Calcutta on screen. Kanchan is helped in the city by people on the fringes of society. One is a teacher who has turned to peddling on the streets – a subtle jibe at what Calcutta does to a person’s right to live with dignity. Another benefactor is an ageing domestic maid. A third is a gangster disguised as a magician, a cart puller and a rich girl. In the end the boy comes back home, having summed up that “the city is an aberration.” Ghatak’s focus is on the goodness of ordinary people, a goodness that gets swallowed up by the ‘aberration’ of the machine-driven environment of the city. Obviously, it is Calcutta he is referring to though this time, he refrains from naming it. Ghatak indulged in some technical experiments in this film. For instance, the speed of a particular sound was increased on the transferring table, or, the use of special lens (300) brought forth fascinating results when the wheel of a car appeared to rotate even while the car was static. The use of an 18-mm lens captured objects in their distortion. This is Ghatak’s only film adapted from a novel by the late Shibram Chakraborty.

The songs and the music were composed by the legendary Salil Chowdhury. Another value addition is casting the timeless superstars in all supporting roles – Kali Banerjee, Nripati Chatterjee, Bijon Bhatacharya, Manu Mukhopadhyay, Gyanesh Mukherjee, Jahar Roy, Keshto Mukherjee and so on.

His brutal insight into the nature of a city and its people appears amazing even across long bridges of time and space. With one whip leashing stroke of his directorial wand, Ghatak slashed open the stomach of this vibrating, sick city, revealing its ugly innards, right in front of the eyes of the viewer, till he/she wishes to look away.

Ghatak portrays Calcutta as a victimizer of its people. At the same time, he also shows the city as the helpless victim (a) of refugees pouring in by the thousands, (b) of the galloping poverty, (c) of squalor, which turned the city into a huge drain flowing with human blood, human waste and human desperation. The film closes with strains of the ‘Communist Internationale’ filling the soundtrack. Was this Ritwik’s way of suggesting a Marxist solution to this gross inequality between man and man, family and family?

According to Erin O’ Donnell, in his essay, “Woman” and “homeland”

in Ritwik Ghatak’s films: Constructing post-Independence Bengali cultural identity, (Jump Cut) “Ghatak often situates his preoccupation with the union of East Pakistan and West Bengal within the heart of Bengali society: the family. And through the post-Independence Bengali “family,” Ghatak expresses the radical transformations that occurred within Bengali culture. Ghatak’s ‘families’ are often not the traditional extended Bengali family, but “alternative,” “surrogate” families, like the theatrical troupe in Komal Gandhar or the wandering group of misfits in Jukti Takko Ar Gappo (Arguments and a Story, 1974), who are displaced, urban, lower middle class refugees searching for a home. By utilizing a melodramatic style comprising Bengali, Indian, European and Russian elements, Ghatak visually and aurally articulates a new Bengali homeland.” One is prone to think that perhaps, he remained forever, an “outsider” in Calcutta and never could internalize it within his system as “home.” Yet, he said, “every man is a refugee when he closes his eyes.”

Shoma A. Chatterji is a freelance journalist, film scholar and author based in Kolkata. She has won the National Award twice, in 1991 and 2000. She has authored 26 published titles of which 14 are on different areas of Indian cinema. She holds two Masters Degrees and a Ph.D. in History (Indian Cinema). She has also won a few Lifetime Achievement Awards from different organizations over time.