“You have endowed me with many things

Where will you put me when I’m in ruins

It’s better that you destroy me, oh god

Let my descendants remain in my dreams.”

That is how Arunava Sinha translates the last four lines of Sankha Ghosh’s poem ‘Baburer Prarthana’ (‘Babur’s Prayer’ in English). Composed in the mid-1970s, the poem – also the title of his 1977 book of poetry that fetched him the Sahitya Akademi award in the same year – is perhaps the most memorable lines penned by the most influential Bengali poet of recent years who breathed his last on 21 April.

The poem refers to Mughal emperor Babur who famously prayed to the almighty to save the life of his terminally ill child. The legend also says that Babur offered his own life in exchange for his offspring. What occasioned this reference in the mid-1970s? There are reasons to believe that Sankha babu was responding to the killing spree that marked the early-1970s in West Bengal. Although he never expressed solidarity of any sorts to the Naxal uprising that swept the state, he was deeply pained to see his students at the department of Bengali, Jadavpur University, hounded by the police and killed in the process. It showed in many of his poems written in the 1970s. By invoking a prayer etched in the medieval legends, ‘Baburer Prarthana’ takes a flight of imagination. It also alludes to Bharat Chandra Raygunakar’s immortal lines in the18th century narrative poem Annadamangal where a Bengali boatman – being encouraged by goddess Annapurna to ask for a boon – pleaded that his children should live a life in ‘dudhe bhate’, i.e. in milk and rice. In these lines Sankha babu steps out of comfort zone in style. By refusing to remain cocooned within his primary identity of a teacher in a university of reputation, he embraces the role of a public intellectual who decries state-sponsored terror in the guise of taming a rebellion.

The poem was soon set to tune by Pratul Mukhopadhyay, the self-styled composer-singer who performed it in street-corner meetings and factory gates. Much later, in the wake of Nandigram killings in 2007, it inspired a Bratya Basu play that Kalyani Natyacharcha Kendra produced in the same year. ‘Baburer Prarthana’ became a stuff of legend by itself.

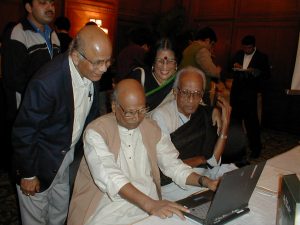

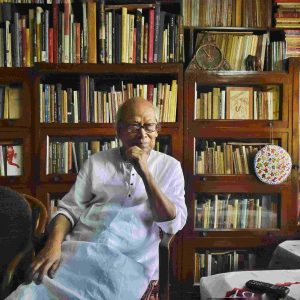

Speaking of the public intellectual that Sankha babu was, it was hardly his comfort zone. He – by his own admission – was a shy person. A teacher and a researcher par excellence, Sankha babu was a naturally gifted orator. But he was comfortable in his classrooms – among his students. He loved to host countless guests who assembled at his deceptively simple Ishwar Chandra Nibas apartment at Ultadanga. However, he spoke very little; mainly through witty interjections and wise observations. He was not known as a raconteur, but he enjoyed good company and besides freewheeling discussions on art and culture, always encouraged fun and banter. As a public speaker, he excelled in commemorative lectures – the ones written down with meticulous detail. Over the last two decades his addresses were few and far between. And the last few years always saw him in tight lips. He loved meeting people, visiting theatres, inaugurating events; but never uttered a word. Not that his words failed him, for he continued writing till the very end; but his speech did.

I remember an evening three summers back at the Academy of Fine Arts. Sankha babu was to inaugurate a theatre festival dedicated to the plays written by Chandan Sen. Bibhash Chakraborty and Ashok Mukhopadhyay were also present. I happened to be the master of ceremonies. Minutes before the start, we were discussing a few things inside the greenroom. I knew that Sankha babu would not speak. However, consent was necessary. I knelt before him, asking whether he would say a few words. Sankha babu drew me closer and then, whispering into my ears, he said, “I won’t be able to, Anshuman. My speech is severely handicapped.”

That was it. His sincerity was unquestionable and his presence dignified. Clad in his customary dhoti and panjabi, teamed with leather sandals, he would grace any stage, lending an aura of authority to it. But he chose his appearances carefully. His preferences were clear, his silence eloquent.

In the last decade and a half, this image of a public intellectual got reinforced time and again. Till his health permitted, Sankha babu took to the streets to protest against any kind of state atrocity – left, right or centre. He spared no one in his words. Words that oozed wisdom of an ancient sage; words that cut through the commonplace, and conveyed something profound and unique.

During the civil society movement against forceful land acquisition and police excesses at Singur and Nandigram, Sankha babu led from the front. I remember a day in 2007. It was the second week of November. Nandigram was on fire for the second time in ten months. A protest meeting was quickly organized at the Academy of Fine Arts approach. Sankha babu lent his weight to the occasion and quoted Ritwik Ghatak to describe the events unfolding as ‘bibhatsa maja’ (‘uncanny fun’). A few days after, he participated in a protest march from College Street to Esplanade. He could have avoided it. He did not. He penned his protest in poetry. He responded to many other incidents in brief statements – joint or individual – issued over phone or otherwise, and then circulated all over. Such was the weight of his words – direct and incisive.

His camaraderie with theatre persons was strikingly warm. None of his generation relied so much on theatre as the expression of our times. A few years back, Koushik Sen requested him to participate in a silent rally urging the administration to ensure free and fair elections – a prerequisite for a democracy to function. Sankha babu arrived. He could hardly walk. Someone would have to support him as he walked. Yet, he walked a mile that evening – from the Academy gates to the Esplanade. It did not create much impact. But Sankha babu made his stance clear.

That he did not align with the rulers of the state made his words and expressions all the more dependable and courageous. In recent years, a large section of the civil society patiently waited for his insightful statements. They saw him as their friend, philosopher and guide; his statements as vision documents.

Three years back, the ruling party seemed to have made a mockery of Panchayat elections. Sankha babu responded with a poem that demolished the carefully crafted narrative of ‘unnayan’, i.e. development, and exposed the demoniac intentions of the ruling party’s election machinery. It made headlines in no time, made many a heads turn and invited sharp reactions from the perpetrators of violence. Sankha babu remained unperturbed.

Now that the state of West Bengal is experiencing the most decisive electoral battle in years – an election that could end up transforming the fabric of the state – Sankha babu’s death might spell doomsday for the struggling civil society movement clearly lacks a leader. There are a few others who command reverence and authority. But Sankha Ghosh was a class apart. He was – as his former colleague Pabitra Sarkar put it in a late evening Facebook post – was the last of a generation. A generation that shaped the state of West Bengal since it was born.

Image courtesy: TCG archive, Sanjeet Chowdhury, Wikimedia Commons, Facebook, Amazon.

Anshuman Bhowmick is a cultural commentator based in Calcutta aka Kolkata. Among many other things, he reviews theatre for a leading English daily and a prominent Bengali periodical and represents Bengali theatre in national and international forums. A widely travelled man equally at home in West Bengal and Bangladesh, Anshuman is curious about everything related to Bengal - past, present and future.

One Response

অসাধারণ হয়েছে লেখাটি