Almost every ancient society in the Mediterranean region had its religious festival commemorating the death and rebirth of a god whose fortunes represented the pattern of death and regeneration in nature. For example, at the December solstice, which is known also as the winter solstice, the shortest day in the year in the northern hemisphere, the ancient Greeks celebrated Dionysia, the festival of Dionysus, the god of vegetation and nature. In the shortened days and the withering and waning vegetation in winter, people perceived images of death and decay in nature. They feared that these unsolicited undesirable changes in nature could affect their god of vegetation and nature adversely leading to his death. If a god could be affected by the corrupting influence of nature, what would be the fate of the mortals? Hence, they considered themselves also to be subject to the same fate as their god. However, they also perceived that these adverse changes in nature were inevitably reversed with the advent of spring. In the lengthening of the duration of the day and the regeneration of nature in spring, they perceived the rebirth of their god. Hence, to commemorate the fortunes of Dionysius — his mystical death in winter (symbolized in the shortened days and death and decay of all vegetation), his miraculous rebirth in spring (symbolised in the longer days and rejuvenation of nature) and his supposed struggles in passing from one state to another, and to identify their fate with that of their god, the ancient Greeks celebrated the festival of Dionysia.

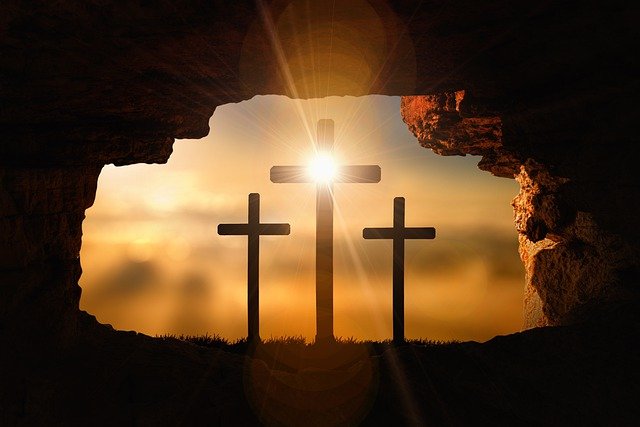

Christianity which was born in the Mediterranean region two millennia ago also has its discourse on the death and resurrection of a god. The Paschal Mystery, the discourse on the death and resurrection of Jesus, the incarnate Son of God, is the central theological doctrine of Christianity. Jesus’ passing through death, his rising from the dead and his ascension culminating in his union with his Father in heaven and their effects on humanity in terms of human salvation are the dynamics of the Paschal Mystery. According to the Christian worldview, the entire human history not only leads to but also receives its significance from the Paschal Mystery. Easter is the celebration commemorating the resurrection of Jesus three days after his death and burial, the pivotal dimension of the Paschal Mystery.

The liturgical celebration of the Paschal Mystery is called the ‘Paschal Vigil,’ known also as the ‘Easter Vigil’ which evolved out of the early Christian practice of keeping watch through the night and meditating on the mighty works of God until the earliest hours of the morning when Christ’s resurrection was acclaimed. The Christian community borrowed both the name and the date of the solemn event of the Paschal Vigil from the Passover Feast of the Jews. For the Jews, the Passover Feast is the commemoration of the event of God passing over the houses of the Israelites sparing their lives and destroying every first-born son of the Egyptians on the night He delivered the Israelites from their slavery in Egypt. Symbolically and spiritually, the Passover commemorates the passing over of the Israelites from their slavery to freedom through the direct intervention of their God, Yahweh. During the Paschal Vigil, Christians commemorate the passing over of Jesus from death to life by means of his resurrection. Symbolically and spiritually, for them, it is also a celebration of their passing over from sinfulness to a new life in Christ. It is the celebration of their death to sin and rising to a new life in Christ. The Easter Vigil liturgy marks the beginning of the celebration of Easter.

Among the various theories trying to explain the origin of the term, Easter, the theory of the seventh-century English scholar and monk, St. Bede the Venerable, remains the most widely accepted one. Bede argues that the name, Easter, comes from the name of the fertility goddess, Eostre, known also as Eastre, of the Anglo-Saxons, the ancestors of the English people. As the goddess of fertility, Eostre presided over conception, birth, flowering, pollination, ripening of fruits and so on in nature. At the end of a harsh and gloomy winter characterised by scarcity, she ushered in a warm, fecund and regenerating spring characterised by abundance in nature.

According to Bede, the Anglo-Saxons referred to their month coinciding with the modern-day April by the name, ‘Eostur monath,’ after their pagan goddess, ‘Eostre,’ known also as ‘Eastre.’ They also referred to the season of spring by the name of their goddess. In the middle of the second century, the festivities commemorating the resurrection of Jesus emerged as an important Christian celebration. Since the Christian festivities fell in the month named after the goddess Eastre, the Anglo-Saxons who embraced Christianity began to refer to their festival by the name Eastre which they eventually changed to ‘Easter.’

The ancient Greeks celebrated the festival of Eastre on the first full-moon day following the spring equinox, the date on which the day and night are equal, and which marks the end of winter. All four accounts of the evangelists agree that the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus took place on the Sunday after the Passover festival. As per the Jewish calendar, the Passover begins on the fifteenth day of the Month of Nisan falling somewhere between 27 March and 24 April. Unlike our contemporary civil calendar, which is based on the twelve solar months, the Jewish calendar is based on the twelve lunar months, and it is carefully adjusted to ensure that each month begins on the first day on which the new moon is visible. As a result, the Passover that falls on the fifteenth of Nisan coincides with the full moon every year. During the Council of Nicaea held in 325, the Church set aside the Sunday after the first full moon following the spring equinox for the celebration of Easter. Since the spring equinox in 325 fell on 20 March, the church decided that for the days to come, Easter should be celebrated on the first Sunday after the first ecclesiastical full moon after March 20. As a result, Easter may fall somewhere between 22 March and 25 April.

Bede argues that the name, Easter, comes from the name of the fertility goddess, Eostre, known also as Eastre, of the Anglo-Saxons, the ancestors of the English people. As the goddess of fertility, Eostre presided over conception, birth, flowering, pollination, ripening of fruits and so on in nature.

The Western Churches schedule Easter based on the Gregorian calendar and the first Sunday after the first ecclesiastical full moon after March 20. The Eastern Orthodox Churches on the other hand schedule Easter based on the Julian calendar (which is 13 days ahead of the Gregorian calendar) and the actual first full moon after the spring equinox. Therefore, these two different churches celebrate Easter on two different dates most years.

When Christianity began to take deeper roots in the Mediterranean regions, the church realised that the centuries-old pagan festival of Eastre was a significant part of the cultural and religious makeup of the Mediterranean people, and hence it was rather difficult to obliterate the pagan influence on the new followers of Christ. Therefore, Christianity adapted and baptised some of the prevailing pagan practices for practical reasons. For example, like most ancient deities in all civilizations, Eastre also had her favourite companion animal. It was the rabbit, a symbol of the moon, springtime, sexuality, fertility and immortality in European folklores, who was fortunate to be Eastre’s favourite companion. The legend has it that Eastre transformed a bird into a rabbit before choosing it as her favourite animal which would continue keeping its habit of laying eggs even after its magical metamorphosis.

Christianity adopted the legend of the egg-laying rabbit into their Easter celebrations under varying names such as Easter Hare, Easter Bunny and Easter Rabbit. As per a German folkloric tradition, the Easter Rabbit lays red eggs on Maundy Thursday while it lays eggs of various colours on the night before Easter. At Easter, children build rabbit nests in their homes and in their gardens in expectation for the Easter rabbit to come and lay eggs at Easter. While the well-behaved children are believed to find their nests filled with colourful eggs as they wake up in the morning, naughty children are believed to find their nests filled with rabbit droppings, coal, mud and other obnoxious things. The visiting rabbit is also believed to leave behind baskets full of candies and pastries in the homes of people.

Since the egg is a symbol of new life and hope, and also perhaps because of its association with the Easter Rabbit, the practice of exchanging dyed and decorated eggs as gifts and playing games such as ‘Easter egg hunts,’ ‘egg tapping,’ and ‘egg rolling’ on Easter morning became part of the Easter celebration. The practice of hanging colourfully decorated eggs on a small tree or bush gave rise to the concept of the ‘Easter egg tree’ which serves as a symbol of new life as well as festive decorations.

As per a Polish legend, the practice of exchanging coloured and decorated eggs at Easter goes back to the practice of Mother Mary colouring and decorating eggs for the amusement of Jesus when he was a baby. A Ukrainian folktale holds that the practise goes back to Simon of Cyrene, an egg seller who helped Jesus carry his cross to Calvary. After Simon helped Jesus carry the cross, he went back home to notice that all the eggs in his basket always turned mysteriously colourful — a colourful reward from Jesus to Simon.

According to a Romanian legend, the colourful Easter eggs take their origin from Mother Mary’s failed attempt to bribe the Roman soldiers with a basket of eggs to spare the life of her son. The soldiers were unmoved by the eggs offered to them as gifts and they went on with the job of crucifying Jesus. As the disheartened and helpless Mary stood crying by the cross, she noticed the blood dripping from the crucified body of her son splashing onto her egg basket turning the eggs red. As the eggs began turning red, in memory of this event, Jesus asked his mother to gift red-coloured eggs to her friends after his resurrection. In obedience to her son’s request, after his resurrection, Mother Mary greeted everyone by saying, ‘Christ is risen’ and gifted them with red eggs. Since a believer’s eyes of faith invest everything, be it pagan or cultural, with religious significance, while the red colour on the egg becomes symbolic of the blood of Christ, the egg itself becomes symbolic of Jesus’ tomb. The cracking of the egg becomes symbolic of Jesus’ emergence from the tomb or his resurrection.

Images courtesy: Wikimedia Commons, Pixabay

Sacaria Joseph is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at St. Xavier’s College, Kolkata. Having pursued his undergraduate studies at St. Xavier’s College, he furthered his academic journey by obtaining a Master of Arts degree in English Literature from Pune University, a Master of Philosophy from Jadavpur University, Kolkata, and a PhD from Visva-Bharati University, West Bengal. In addition to his academic pursuits, he writes on a wide array of subjects encompassing literature, philosophy, religion, culture, cinema, politics, and the environment.