Guess what was Satyajit Ray’s prized possession on his 4th birthday? It was a pygmy phone, a toy gramophone with a tiny record, manufactured by Bell Telephone Company. It had a few musical pieces like ‘The Blue Danube’, ‘Tipperary’ and ‘Over the Waves.’ That was how Ray developed his taste for western music, which was to stay with him lifelong.

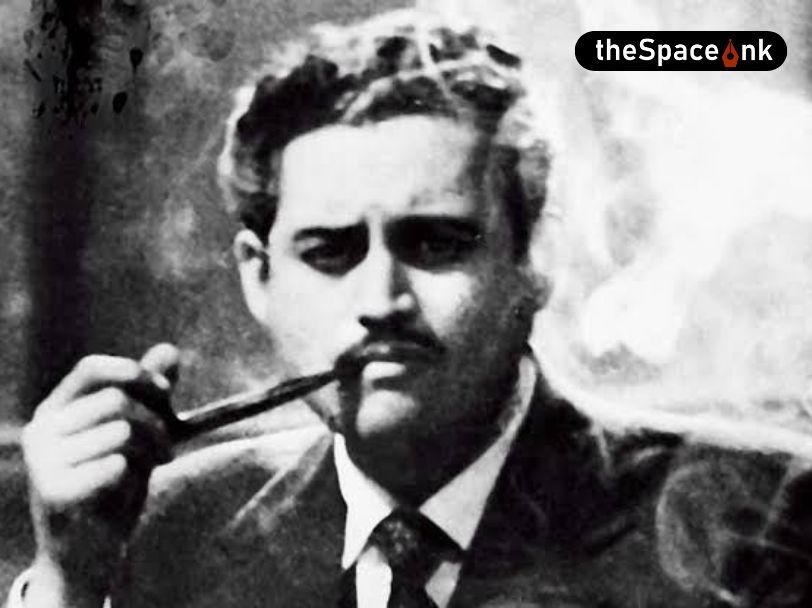

Jnanpith Award-winning poet Bishnu Dey became a western music enthusiast from his college days in the late 1920s. His teacher, Professor H Crabtree played Johann Sebastian Bach on the college chapel organ. Young Dey, then a student of St Paul’s College, would often accompany another teacher, Reverend Milford, to his cello and double bass concerts at The Calcutta School of Music.

Ray and Dey represent the long line of western music connoisseurs in the city, who have promoted this form over generations, starting from the second half of the 19th century.

When we go back in time, the first milestone is 1787. This was when Gerasim Lebedev began his ten-year stay in Kolkata. A man of many parts, Lebedev’s biggest achievement was to stage, for the first time in proscenium style, two Bengali plays in 1795 and 1796. He was also the pioneer in using western instruments for Indian music. An accomplished violinist, Lebedev taught western music to his Bengali tutor Golak Nath Das. During his stay in the city, he had also conducted ten concerts.

Let’s jump a few decades before stopping at the next two destinations. These were the Houses of Tagores in Jorasanko and Pathuriaghata. Rabindranath Tagore in his memoir ‘Jibansmriti’ had written about how his elder brother Jyotirindranath Tagore would create new tunes while playing the piano. Young Rabindranath and a friend Akshoy Chowdhury’s assignment was to rustle up the lyrics.

Says Subha Das Mollick, the maker of ‘Calcutta Sonata’ a documentary on the piano in 2018, ‘Jyotirindranath was the first to play Indian ragas on the piano but he played Chopin’s compositions with equal finesse. Though Jyotirindranath never went abroad, he was a regular visitor to the western concerts held in the city. His critical appreciation is recorded in his essay on the subject. No wonder, Tagore followed in the footsteps of his Jyoti Dada.’

Adds Jyotishka Dasgupta, president, The Calcutta School of Music (CSM), ‘In those days, musicians of various disciplines frequented the House of Tagores in Jorasanko. As a result, many members of the family became recipients of rich aural awareness.’

Jyotirindranath was the first to play Indian ragas on the piano but he played Chopin’s compositions with equal finesse. Though Jyotirindranath never went abroad, he was a regular visitor to the western concerts held in the city.

Subha Das Mollick, maker of ‘Calcutta Sonata’ a documentary Tweet

From the Pathuriaghata house, Sourindra Mohan Tagore was the foremost music exponent. For his extensive work in musicology he received ‘doctorate of music’ degrees from the universities of Philadelphia in 1877 and Oxford in 1896. Among his books were ‘Victoria Geetimala’ and ‘Harmonium Sutra.’

A few years before his first voyage to London with brother Satyendranath in 1878, Rabindranath had read Thomas Moore’s ‘Irish Melodies.’ His interest in the subject grew during his stay at Dr Scott’s house in London. Dr Scott’s daughters were proficient in singing Scottish and Irish ballads. It was here that Tagore first heard Robert Burns’ ‘Auld Lang Syne’ and ‘Ye Banks & Braes’ O’ Bonnie Doon.’

Soon after his return to Kolkata, Tagore staged two back-to-back dance dramas on the Jorasanko Thakurbari terrace, ‘Balmiki Prativa’ in 1881 and ‘Kal Mrigaya’ in 1882. Some of the songs there bore the indelible imprint of Scottish and Irish Ballads Tagore had heard in Great Britain. Thus, ‘Ye Banks & Braes’ became ‘Phule Phule, Dhole Dhole’, ‘Robin Adair’ became ‘Shokoli Phuralo’, ‘Nancy Lee’, the popular sailor’s song, became ‘Kali Kali Bolo Re Aaj.’ A few years later, ‘Auld Lang Syne’ was transformed into ‘Purano Shei Diner Katha’ and found its way into an anthology, ‘Prem O Prakriti.’ This is one song almost all Bengalis know by heart. There were similar instances in Tagore’s third dance drama ‘Mayar Khela’ (1888) too.

Tagore’s nieces Prativa Devi, Sarala Devi and Indira Devi inherited his love for western music. All were accomplished piano and organ players. Says Subha Das Mollick, ‘In early 20th century Kolkata, educated middle class Bengalis, especially from Brahmo homes, hired imported pianos from shops like Harold’s or H Paul & Co for musical training of ladies of the house. Those who could not afford the piano, went for the table organ.’

According to Das Mollick, ‘The best thing was the indigenisation of the piano. As many of these ladies were not conversant with Western music, they mostly played Indian melodies on the piano. This practice reached its peak much later from the 1950s under V Balsara.’

Dasgupta of CSM agrees. ‘Proficiency in piano, organ, violin or ballroom dancing was a sure way to climb the social ladder and waltz into high society, primarily by marriage.’

Two examples come to mind. Incidentally both are film adaptations of two celebrated Tagore novels, written seven years apart, in 1909 and 1916. In ‘Gora’ (1938), directed by Naresh Mitra, we see Sucharita and Lalita singing ‘Shokhi Pratidino Hai’ with piano accompaniment. In ‘Ghare Baire’ (1984), directed by Ray, we see the heroine Bimala singing a ballad along with her music teacher Miss Gilby on the piano, ‘Sing me the songs I delighted to hear/Long, long ago, long ago.’

Two of Tagore’s contemporaries, Dwijendra Lal Roy and Atul Prasad Sen were also influenced by Western music during their study stints in London and trips to Europe. The Gondoliers of Venice inspired Sen to compose ‘Utho Go Bharata Lakshmi’ while Western movements are evident in Roy’s ‘Banga Amar Janani Amar’ and ‘Amra Malaya Batashe.’

Meanwhile, Trinity College, London, almost a decade after conducting international examinations in music, opened its first centre in India in Kolkata (then Calcutta) in 1886. Dasgupta of CSM came up with an interesting anecdote on the subject. ‘Sometime in the 1980s, a lady examiner came from the UK. While we were on a trip to Jamshedpur, she told me, ‘You know, my mother-in-law appeared for this same Trinity College music exam from Calcutta in 1914. My father-in-law, an army officer, was then based there. So you see, I have a strong Calcutta connection.’

Around the same time (1914), Philippe Sandre, a French violinist, who was already with an orchestra, was toying with the idea of setting up a Western music school in the city. In November, 1915, his dream came true. The Calcutta School of Music (CSM) was born at 24, Park Mansions. In this enterprise, Sandre was ably supported by his co-musicians, pianists Mrs Everett and Lady Woodruffe. CSM became the first western music school in India, too.

Around the same time (1914), Philippe Sandre, a French violinist, who was already with an orchestra, was toying with the idea of setting up a Western music school in the city. In November, 1915, his dream came true. The Calcutta School of Music (CSM) was born at 24, Park Mansions. In this enterprise, Sandre was ably supported by his co-musicians, pianists Mrs Everett and Lady Woodruffe. CSM became the first western music school in India, too.

After a stint in the First World War, Sandre was back as CSM principal in 1919. By 1920, half of the students at CSM were of Indian descent. Initially, lessons were offered in violin, piano, chamber music and singing. In the 1930s, CSM shifted to a new address on 43, Wellesley Street. After Sandre left, Senor Francisco Casanovas took up the reins and built the Calcutta Symphony Orchestra. With him began the CSM tradition of bringing foreign musicians to Kolkata.

Image courtesy: Calcutta School of Music, Subha Das Mollick

References:

1. The Calcutta School of Music – A Symphony Centenary.

2. Shilpe O Sangitey Bishnu Dey. Article in ‘Desh’ (2.4.21 issue) fortnightly by Jishnu Dey and Meera Dey

3. Robijiboni. Prasanta Kumar Pal. Ananda Publishers

4. ‘Music I Live by.’ Satyajit Ray in conversation with Bulbul Sarkar on AIR . YouTube

Abhijit Sen spent nearly two decades as a senior journalist for a renowned English daily. He now divides his time between writing columns, listening to music and watching movies of his choice. He also likes to sing songs composed by Rabindranath Tagore.