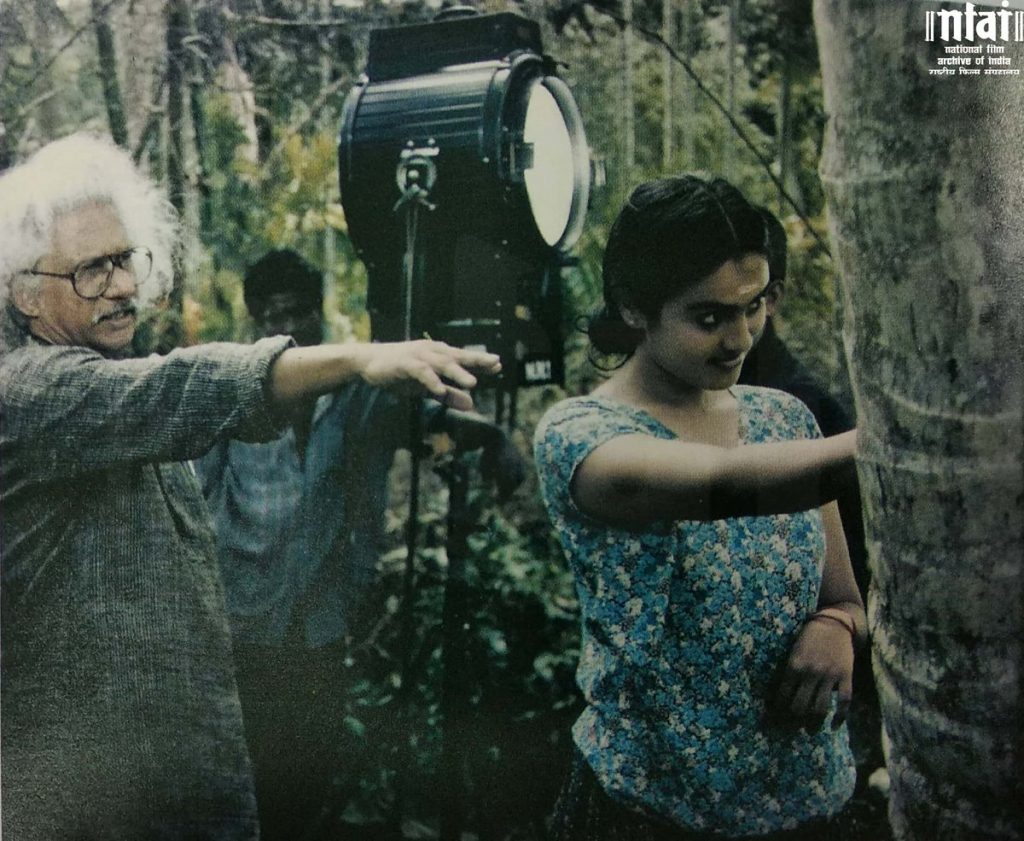

Adoor Gopalakrishnan is an outstanding filmmaker in Indian cinema. He has held on to his own language, style, approach, story and plot and is a name to reckon with on the map of International Cinema. Yet, he has never compromised with market pressures or audience demands for mainstream entertainment. He has made relatively few films during his fifty-year long span as filmmaker.

His first film Swayamvaram (1972) came ten years after he graduated from the FTII, Pune. It was the second Malayalam film after Chemeen to have won the National Award. Followed Kodiyettam (1979), Elipathayam (1981), Mukhamukham (1984), Anantaram (1987), Mathilukal (1989), Vidheyan (1993), Kathapurushan (1995, Nizhalkuthu (2002), Naalu Pennugal (2007), Oru Pennum Randaanum (2008) and Once Again, (2016), on forced migrant labour and the shocking behavior a man’s disappearance can have on the surviving family, has not been written about much as it is considered as lacking Adoor’s signature.

There is no well-known film festival across the world that has not screened his films. Several documentary films were made on him, the most outstanding one was by filmmaker Girish Kasaravalli which won the National Award. Critics and scholars like Suranjan Ganguly, Parthajit Barua and Gautaman Bhaskaran have authored entire books on his works and there is a collection of essays by Lalit Mohan Joshi and V.S. Venkideswaran besides six books in Malayalam by different authors. Yet, at 80, he remains as low-profile and as adverse to the limelight as he is to any negative criticism of his films. That is Adoor Gopalakrishnan for you.

Adoor’s reluctance to identify himself with an ideology, his explorations of the individual, often on a one-to-one basis that spans several layers of the human experience, his insistence on the autonomy of the form in cinema, distinguish him from most of his peers, and often make him a subject of controversy, principally because he belongs to Kerala, forever a volatile political state with polarized agendas preached and practiced by a segmented audience.

“I interact with the medium of cinema by choosing a human being placed in a certain situation. It may be a village simpleton, a disillusioned political worker or a writer as the case may interest my creative instincts and me. It is their existential situation that my film explores. None of this can be summed up through a slogan,” he adds. Adoor insistently refuses to reduce any of his narratives to a cause-and-effect confrontation between the lily-white and the pitch-black. In a much-understated way, his films deal with human ‘absences’ and sometimes, small ‘presences’ that mark that vital difference between Adoor and other filmmakers.

Mathilukal for instance, has no female presence though the female character is very much present across the wall, with her sensuous voice breaking the barrier of the wall that separates her from her ‘lover’ on the other side. In Vidheyan, Patel’s wife, played by Tanvi Azmi, appears briefly but leaves a strong impact. The exploitative and dictatorial landlord (Mammootty) sits on a shaky old chair of which, an arm is missing, a metaphor for the slow and steady collapse of power which he is not even aware of.

“I do not approve of direct political statements because they are one-dimensional. A metaphor offers me more potential to be creative. Through it, I can comment more effectively about the senseless violence around us today. My objective is to draw the maximum out of the film medium. This exploration does not presuppose a signification, though it does not exclude suggestions, gestures. If it renders itself to an identifiable social message, it is for the reader who may have read it. I did not mean it. If someone finds Mathilukal a plea for jail reforms, or Vidheyan a critique of the brutality of feudalism at its naked worst, I cannot help it. In my way of looking at things, all I can say is that they often mistake the incidental for the essential,” he says.

Mukhamukham concerns itself with a political worker with a lot of fire in him who has an inspiring presence. He disappears one day, believed to have been killed, returns after ten years, now an alcoholic. The frustration, the embarrassment and the subsequent anger that builds within his followers culminates in his mysterious murder. But in death, he is resurrected as a hero. Set against the political history of Kerala between 1955 and 1965, this is a much-misunderstood film. But essentially, it is about the frustration of masses set adrift by the inadequacy of the leadership, both past and present. The film operates at three levels – memory, fiction and reality. The first part is memory, the second is fiction and the reality that evolves out of the first two segments forms a major part of the film’s denouement.

I interact with the medium of cinema by choosing a human being placed in a certain situation. It may be a village simpleton, a disillusioned political worker or a writer as the case may interest my creative instincts and me. It is their existential situation that my film explores. None of this can be summed up through a slogan

Adoor refuses to accept that Mukhamukham is a political film. But viewers feel that the film is a subtly handled political film. It is a subtle comment on the Marxist movement in Kerala. But Adoor says that it is neither a political film nor is it a value judgement on the Communist Party of India. While addressing the audience during the first screening of Mukhamukham in Mumbai in December 1985 he said:

“It is about the search of the Self by a revolutionary, his transformation into an image and the ‘demands’ made on that ‘image’ by the people. This is a common truism in Indian politics. In an important scene in the film, I have used Lenin’s quotation: ‘The proletarian movement passes through several stages of growth. At every stage, a set of people stagger, stop and are unable to continue the forward march.’ The film depicts one such movement. There is a revolutionary concealed within every individual. At some point of time, this spirit vanishes. I thought it would be worthwhile searching for that spirit.”

Based on his story, for which Adoor also wrote the script and the dialogue, Kathapurushan offers a deep insight into a span of historical time in Kerala which saw a series of socio-political changes unfolding through the life story of a fictional character named Kunjunni, brought up totally without a father-figure in a Kerala village, under the protective affection of a strong grandmother. The mother is forever ailing, and so full of self-pity for the breakup in marriage that she fails to play mother, let alone, both father and mother to Kunjunni. He grows up in this predominantly woman-dominated ambience (which includes the maid’s daughter, Meenakshi) trying to create his own space within the constraints life ordains for him.

The film reveals several layers while weaving the political history of Kerala over the past 50 years and its influence on the lives of its predominantly agrarian people. The changes that define Vasu’s life reflect the political changes in Kerala as it moves very definitely from post-Independence Gandhism to the Marxist Left to Mao to saffron asceticism used as a veil for the reality of materialism. Kunjunni’s father’s affluence and dictatorship are underscored with his very absence from the visual and narrative space. Kunjunni’s friends from his political space form a representation of the diaspora of the post-Independence young man.

Understatement in craftsmanship is one of the hallmarks of Kathapurushan. Low-key natural lighting blends the characters into their rural milieu. The cinematography (Ravi Varma) captures the richness of the Kerala landscape without making it a touristy picture of visual imagery. The backdrop becomes a part of the narrative as vehicles of transport from the bicycle to the scooter to Kunjunni’s father’s opulent car form visual metaphors of the industrial change on the one hand and class distinctions on the other. Adoor takes the fifty-year time-frame with excellently conceived flashbacks that jump over years in a single, smoothly edited shot. One is reminded of Orson Welles’ invention of ‘lightning mixes’ in which the sound continues, although from a different source, while the scene cuts or dissolves to a new locale or time. Adoor thus, releases the flashback from its conventional status of being an unwanted interruption of a smooth narration.

Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Naalu Pennugal (Four Women) won the Swarna Kamal at the 55th National Film Awards in 2007. The citation said that the award was for his delicate and subtle handling of gender issues in a conventional society. Four women of different marital status are trivialized and subjected to abject neglect by their immediate partners and family.” The film comprises four stories by Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai, one of the most noted and prolific authors in Malayalam literature.

Thakazhi was a powerful source because, says Adoor, “I grew up reading his short stories and novels. He wrote more than 400 short stories and over 40 novels. Chemeen was based on one of his novels. Thakazhi wrote mostly about Kuttanad, an area of backwaters and rice fields where he was born and where he lived practically all his life. His writings are largely about this land and its people. They are true to life apart from being insightful. I re-read his works a couple of years ago with the idea of finding interesting material for a film. Instead of one, I found stories for two films. For Four Women, I have kept the stories independent of each other and at the same worked on an internal thematic connection between them – that of a growing awareness among women.”

Four Women is made up of four short stories. The social comments evolve from within the women themselves. The prostitute is not allowed to lead a life of dignity because the police will not let her. In the Virgin, a young woman who is duped into marriage to an impotent man is deserted by him, leaving her to cope with her virginity in a sham marriage. The Housewife and the Spinster are simultaneous explorations of a woman’s unfulfilled desires of motherhood and lack of a normal sex life presented in two different ways. In these films, Adoor’s mastery over the medium of cinema finds expression through his intense emotional attachment backed by his craftsmanship. His technique is brilliant, the most striking is his power of understatement and his ability to resist all temptations of surrendering to intellectual pretensions.

In fact, like Kathapurushan, this film does not need any inner reading because it stands by itself by the sheer beauty of their quiet statement. Low-key natural lighting blends the characters into their rural milieu while the cinematography maintains the richness of the Kerala landscape without subjecting it to touristic, picture-postcard-like visual images.

Oru Pennum Randaanum (A Climate of Crime) is also based on Thakazhi’s short stories. It is about crime in different contexts and situations.

Four Women argues the cause for four different but ordinary women, who, even under pressure, are able to sustain control and discipline over their lives. There are no value judgements, moralizing, or feminist slogans. It is precisely the softness of the understatement, and the whisperings of gentle articulation that define the mellowing of the filmmaker called Adoor Gopalakrishnan.

Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Naalu Pennugal (Four Women) won the Swarna Kamal at the 55th National Film Awards in 2007. The citation said that the award was for his delicate and subtle handling of gender issues in a conventional society.

Adoor has remained loyal to the time, place and character setting of the original stories but has added his own inputs to the celluloid versions. The films reveal a mellowing of the simmering anger seen earlier such as Swayamvaram, Vidheyan, Mathilukal, and so on. The social comment in Elipathayam returns in Oru Pennum Randaanum and Naalu Pennugal in a soft, gentle manner, like a soft caress of the spring breeze against your cheeks, tears unshed, words unspoken, yet deep, intense and scathingly incisive critiques about prevailing social conditions at that time. Interestingly, these comments are universal that cut across time, place and person. The films are character-centric.

His oeuvre in cinema explores the interconnectedness of human beings placed within different contexts, some sourced from literature and some springing from original ideas to unfold in layers, the struggle or lack of struggle in men and women within specific time-space paradigms. His cinema is unique because of his gift for understatement marked nevertheless by razor-sharp, scathing indictments on feudalism, patriarchal dominance and capitalistic exploitation. Sometimes they are dotted with a movement towards egalitarian thinking, an idealistic, democratic approach to life and emancipation.

All the films he directed, from Swayamvaram (1972) to Oru Pennum Randanum (2008) won him several national and international awards. The National Award was bestowed on his films sixteen times, the Kerala Sate Film Awards seventeen times, and the British Film Institute Award for Elipathayam which dealt with the tragedy of an idle, lotus-eating man who exemplifies selfishness, personal failure and subtle violence in a way that destroys the lives of those he lives with. The film bagged the Sutherland Trophy at the London Film Festival in 1982.

He was bestowed the Dadasaheb Phalke Award for his rich contribution to cinema in 2004, besides the Padma Shri (1984) and Padma Vibhushan in 2006. He has also made over 30 short films and documentaries of which The Chola Heritage won a Special Jury Award at the National Awards (1980). In 1984, he won the National Award for Best Writing in Cinema for a collection of essays on cinema under the title Cinemayude Lokam. In 2003, the French Government honoured him with Commandeur Des Arts et Lettres order for his outstanding contribution to international cinema.

The gentle, caressing way in which cinema can be used to tell apparently simple stories with depth and power is perhaps being seen after a long time since Ray’s Apur Sansar. The love of the filmmaker for his medium, his craft, the stories and the characters within them come across through these films so eloquently and softly that they keep haunting one much after the film is over.

His cinema is unique because of his gift for understatement marked nevertheless by razor-sharp, scathing indictments on feudalism at its worst, patriarchal dominance, capitalistic exploitation sometimes dotted with a movement towards egalitarian thinking, an idealistic, democratic approach to life and emancipation. His cinema reveals several layers of meaning while weaving in the political history of Kerala over the past six decades or more and its influence on the lives of its deceptively ‘simple’ folk. His films are examples of brilliant technique. Understatement in craftsmanship is one of the hallmarks of his films. Low-key natural lighting blends the characters into their rural milieu while the cinematography maintains the richness of the Kerala landscape without subjecting it ever to touristic, picture-perfect, postcard-like visual images. His cinema does not demand inner readings and stands by itself even at face value.

Shoma A. Chatterji is a freelance journalist, film scholar and author based in Kolkata. She has won the National Award twice, in 1991 and 2000. She has authored 26 published titles of which 14 are on different areas of Indian cinema. She holds two Masters Degrees and a Ph.D. in History (Indian Cinema). She has also won a few Lifetime Achievement Awards from different organizations over time.