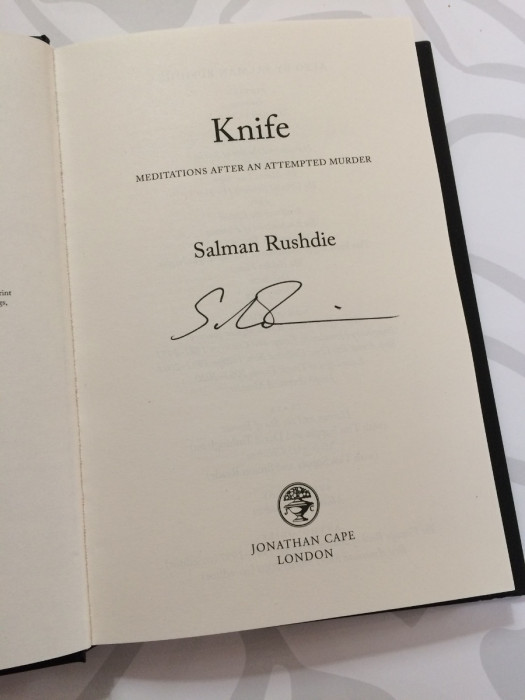

Knife: Meditations After An Attempted Murder. By Salman Rushdie. Penguin Random House India, 2024. Pp. 211. Rs 699.

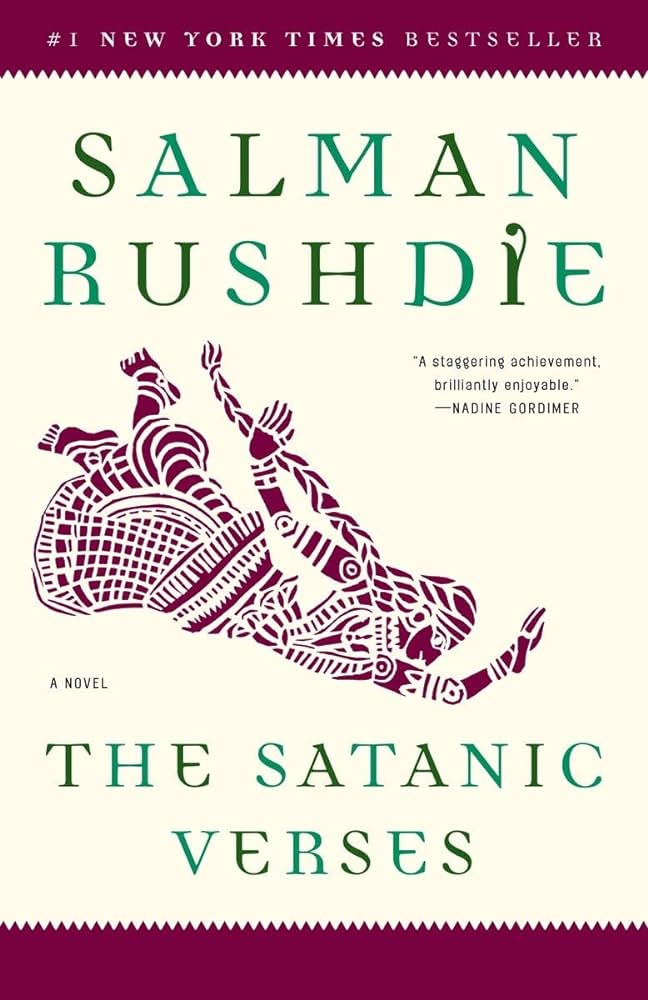

I was a high school student when Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses was published. The book was immediately labelled blasphemous by many Islamists because of the way it spoke of Islam. The Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran’s supreme religious leader, issued a fatwa against Rushdie as well as his publisher. It urged followers to kill Salman Rushdie as an act of revenge for the perceived insult to Islam. The Indian government, too, quickly banned the book, thereby giving it the additional visibility all banned books gain!

My English Language teacher somehow managed to procure a copy of the book, and he was generous enough to lend me the book along with the customary warnings. I remember flipping through it and quite failing at that age to understand what the brouhaha was all about! The book quickly slipped out of my consciousness. Now, more than three decades after the ban, Rushdie’s new book, Knife, brings back to life the memories and the debate about Satanic Verses.

After the fatwa, Rushdie became a symbol of resistance on the part of writers who were threatened because of what they wrote. He became a symbol of artistic freedom. But this came at a cost—the threat always persisted in the background, even as he lived a life surrounded by security personnel. And this threat finally manifested itself in an attack on August 12, 2022, as Rushdie took the stage at a programme to speak ironically about the need to ensure writers’ safety. Knife is about this attack, Rushdie’s response to it, his attempt to understand his assailant’s mind, and finally, his attempt to reclaim his space as a free-speaking writer who refuses to be cowed down by threats and attacks.

The cover of Knife makes an immediate visual impact.

It is at the same time simple and brutal and gives the impression that a knife wound has been inflicted on the book. Apart from the visual impact this image creates, it has multiple meanings as one who reads through the book will realize. After all, Rushdie sees the act of writing the book as striking back at the knife assault and the ideology that spurred it on. The very presence of this book, and the very candid way the writer shares his thoughts on the incident, are Rushdie’s way of proclaiming that terrorist attacks cannot create more than a cosmetic effect on the freedom of writers.

Knife starts with a blow-by-blow account of what happened on the day of the attack when a young man dressed in black rushed towards him with a knife in his hand. The description is almost cinematic; at the same time, Rushdie explores his own train of thought in those moments and tries to understand his own reaction to the impending attack.

The attack resulted in Rushdie losing his right eye and contracting several injuries. The assailant was arrested, and is awaiting sentencing. Knife presents a candid account of this process of recovery and of how the writer battles physical pain and mental anguish to claw his way back to a semblance of ‘normalcy’, as he moves from a ventilator to moving his toes to speaking haltingly and finally to writing this book. The attack also occasions an opportunity for Rushdie to revisit the Satanic Verses controversy. And he stands his ground on the controversy, refusing to show any remorse for what he wrote.

One of the most intriguing elements of this novel is the narrator’s attitude towards the assailant, who is simply called A.

Rushdie has no sympathy at all for A and hopes he will get the maximum sentence possible. He is condescending and brutally sarcastic about the man who had read only a couple of pages of the book and decided to carry out the attack based on the indoctrination he had received. He seems to be less than human in Rushdie’s eyes because he lacks agency of his own, because he is unable to think rationally on the matter. And yet, the narrator is fascinated by A, and this causes him to dedicate a substantial section to an imagined conversation between A and himself. It is a conversation he uses to try to understand A, but also to put him in his place. And he does so in his supercilious manner, showering him with undisguised contempt and destroying him and the possible arguments he might have to justify his actions.

Also Read: Power and Glory: Stories of India’s Women Athletes

This imaginary conversation allows Rushdie to posit alternate and oppositional discourses regarding a gamut of concepts such as secularism, God, holy books, the word of God, the value of life, demonization of the Other, love, and curiously, translation, which is a significant trope in this discussion. Exposing the contradictions in the discourse of politicised religiosity, Rushdie concludes that A was condemned to obscurity in spite of his 27 seconds of fame.

Knife is extremely critical of the rise of extremism all over the world from the USA to India. Rushdie bemoans the rise of ‘false narratives’ that are rooted in antiquated religiosity and that facilitate oppression. This is why, he writes, we need writers who would create new narratives which the reader will espouse, rejecting the false exclusionary narratives being bandied about by politicians and extremists. His comments on ‘religious sectarianism’ and ‘political authoritarianism’ and the decline of democracy in India are sure to stir up further controversy in India!

Rushdie also shares his thoughts on personal religion and a more public, politicized religious discourse. He does not need religion, he proclaims, but he appreciates that some people might indeed do. He has no problem with personal religion as long as it remains personal, he writes.

The best way of summing up this book is in Rushdie’s own words—“I tell myself that (this book) is my way of taking ownership of what happened, making it mine—making it my work… A book about an attempted murder might be a way for the almost-murderee to come to grips with the event.”

A racy, personal yet deeply philosophical narrative peppered with literary allusions and parallels, that touches upon some of the most pressing concerns of our times. Well worth the seven hundred rupees you would shell out for this beautifully produced hard cover volume.

All Images: Google

Sayantan Dasgupta is an academic, translator and writer. He is a former journalist, who fancies flirting with his old profession now and then, and stg-thespaceink-tstodaystg.kinsta.coud offers him the perfect opportunity to do so.