(Phnom Penh)

Victor Hugo is widely credited with saying, “He who opens a school door, closes a prison.” That was in the 19th century. Hugo died in 1885. Even today, his words find their way into articles on education. But Cambodia wrote a dark irony against that noble idea.

Cambodia was once a French protectorate. Yet, under the Khmer Rouge regime, a school door was literally shut to open a prison gate. That school was Tuol Svay Prey High School in Phnom Penh. When Pol Pot came to power, the school was turned into a detention center. Its new name: Tuol Sleng Security Prison 21—or simply, S-21.

Also Read: Books That Burst Out of Windows and Spiral Into Infinity- Part 1

I visited Cambodia some time ago. I stayed in Phnom Penh. Like most travelers, I had a list—Angkor Wat, the Royal Palace, the Silver Pagoda, the Central Market. And then, the Genocide Museum. At the time of booking my room, I hadn’t realized how close the museum was. Practically a stone’s throw from my guesthouse. I thought I’d visit it casually on the last day. I didn’t know the weight it would leave on me. (Phnom Penh)

The City of Ghosts

The address was simple—360 Street, Tuol Svay Prey. A peaceful neighborhood. Schools, snack shops, sushi stalls. Just like any other place. But the history here is heavy. In April 1975, the Khmer Rouge forced everyone out of Phnom Penh. They told the people the Americans would bomb the city. They said, “Leave for only three days.” People left their stoves on. They left their doors unlocked. They didn’t come back for four years.

The regime even blew up the National Bank. They abolished money. When the city was finally liberated, the streets were covered in useless banknotes. They were like dead leaves.

Walking toward the museum, I thought about the word “Genocide.” It was coined by Raphael Lemkin, a Polish-Jewish lawyer. He combined the Greek genos (race) and Latin -cide (killing). Standing in front of the old school gate, the word stopped being a legal term from a textbook. It became the smell of old dust and the sight of rusted iron. (Phnom Penh)

“The prison held over a thousand people at once. When arrests increased, so did the torture. Those who didn’t die fast were sent to Choeung Ek—the Killing Fields.”

The School of Shadows

Dictators always have two loyal allies: fear and suspicion. Pol Pot—born Saloth Sâr—wanted to “cleanse” Cambodia. He wanted to restart time at “Year Zero.” No monks, no doctors, no teachers. Even wearing glasses was dangerous; it made you look like an “intellectual.”

In 1976, this school became S-21. Records say 12,000 to 20,000 people were imprisoned here. The prison held over a thousand people at once. When arrests increased, so did the torture. Those who didn’t die fast were sent to Choeung Ek—the Killing Fields.

Inside the museum, the “Discipline of the Security” is still posted on the wall. These are the exact words the prisoners had to live by:

- You must answer accordingly to my question- Don’t turn them away.

- Don’t try to hide the facts by making pretexts this and that you are strictly prohibited to contest me.

- Don’t be fool for you are a chap who dare to thwart the revolution.

- You must immediately answer my question without wasting time to reflect.

- Don’t tell me either about your immoralities or the essence of the revolution.

- While getting lashes or electrification you must not cry at all.

- Do nothing, sit still and wait for my orders. If there is no order, keep quiet, when I ask you to do something, you must do it right away without protesting.

- Don’t make pretext about Kampuchea Krom in order to hide you secret or traitor.

- If you don’t follow all the above rules, you shall get many lashes of electric wire or five shocks of electricity discharge. (Phnom Penh)

These were not rules. They were rehearsals for obedience.

Also Read: Books That Burst Out of Windows and Spiral Into Infinity – Part 2

The Survivors

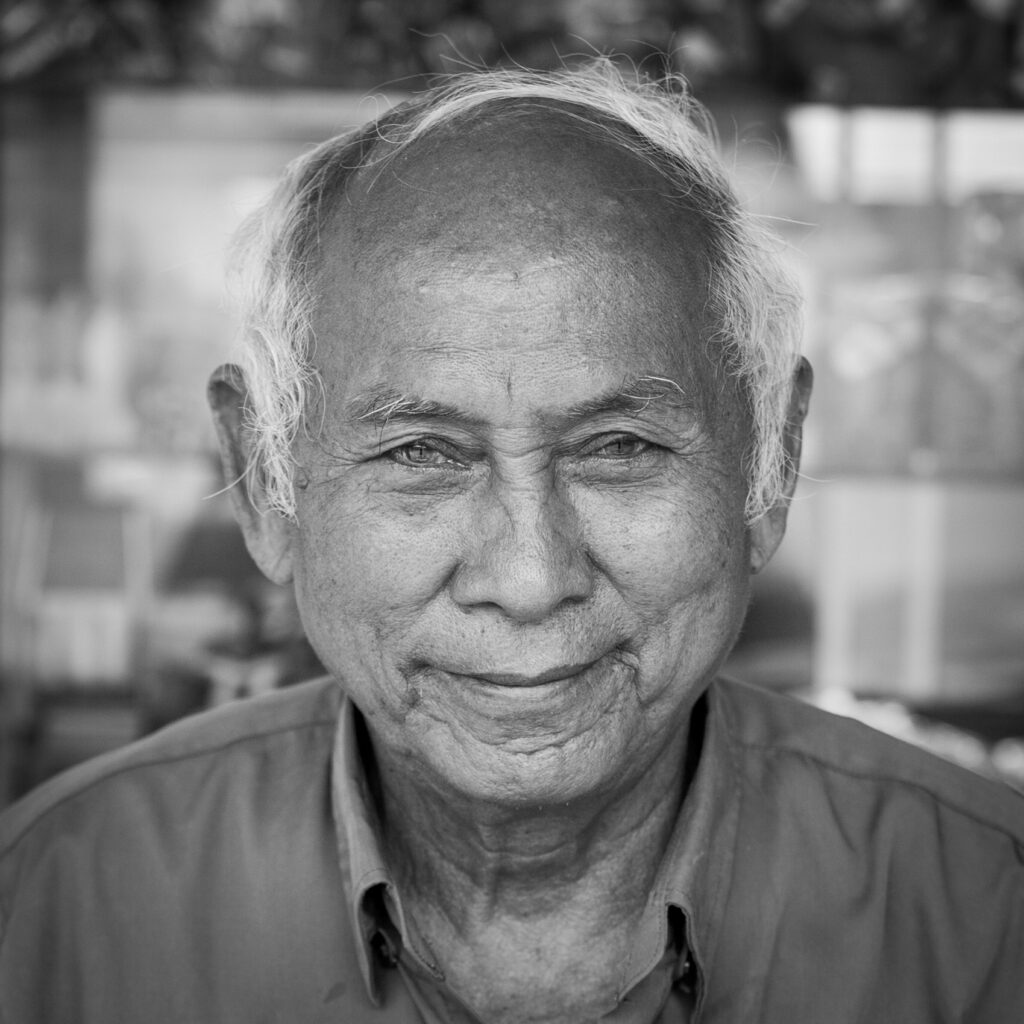

Each prisoner was photographed. The museum shows these faces. Thousands of eyes staring at you. Some look angry. Most look confused.

But among the ghosts, there were survivors. Only a few. They survived because they were “useful.” Bou Meng was an artist. He was arrested with his wife, but he was the only one who came out alive. He was spared so he could paint portraits of Pol Pot. For an artist, it is a cruel mercy—to use your hands to paint the face of the man who took everything from you. Later, he used those same hands to paint the horrors he saw inside, so the world would have proof. (Phnom Penh)

Then there is Chum Mey. He survived because he could fix sewing machines. The Khmer Rouge needed their uniforms mended. Today, one might see a few elderly men sitting at small tables near the museum exit. One could be Chum Mey. He sells his book. He shakes hands with tourists. There is a strange triumph in his smile. A man who was once a “number” meant for execution is now a grandfatherly figure, complaining about the afternoon heat. It gives the visitor a little room to breathe. (Phnom Penh)

The Weight of Silence

In 1979, Vietnamese forces liberated the camp. A year later, it became a museum. What was life inside? Complete records are missing. Many documents were burned. But the iron beds in Block A remain. The tiny brick cells in the classrooms remain. (Phnom Penh)

Kaing Guek Eav, or “Duch,” was the chief of S-21. During his trial, he spoke of “medical experiments.” The tools—saws, pliers, hooks—are still there. Duch told his guards: Do not let them die too quickly.

After spending time there, I took off my headphones. The audio guide was too much. My eyes refused to close, so I gave my ears a break. Others did the same. We sat on benches, staring at the barbed wire.

I asked myself—what does death feel like? Misery, silence, helplessness? (Phnom Penh)

I remembered Albert Camus, The Outsider, Meursault says, “Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday. I can’t be sure.” For him, perhaps death carries no weight. But standing inside S-21, that indifference felt impossible.

I am from the East. A Bengali. An Indian. Here, death does not pass quietly. It lingers. It stains memory. We argue with it, mourn it, ritualize it. We don’t know how to shrug it off. (Phnom Penh)

Image Credit – By Mszelistowski – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0,

History tells us such violence is never truly “foreign.” It only changes language, uniforms, excuses. In India, we have our own scars—Partition, Jallianwala Bagh. Different places, same silence afterward. Camus gives me clarity, but not comfort. My own history gives me memory, but no answers.

A strange sadness grows quietly in the bloodstream. It whispers how cursed we humans can be. (Phnom Penh)

Departure

The next day, I found myself sitting at Kuala Lumpur airport. A layover on my way back to Kolkata. Five and a half hours to wait. The memory of the school-turned-prison was still raw. The departure lounge felt like a dead-end alley.

Outside, it was raining. The tarmac glistened. My weather app predicted a storm. No announcement yet, but I felt the flight would be delayed. (Phnom Penh)

Also Read: The Butcher Who Taught a Monk

I stared blankly and prayed—please, not tonight. Let the Kolkata flight arrive on time. I just wanted to be home.

The rain kept falling. (Phnom Penh)

Photo Courtesy: Author

Pijus Ash is a freelance journalist with over two decades of experience. An avid reader by nature, he likes to pursue independent research. In addition to his passion for reading, Pijus enjoys traveling and frequently embarks on backpacking.