For decades, perhaps even a century or more, the essential template for a day of Test cricket has remained reassuringly unchanged.

Upon starting a batting innings on a summer’s late morning, the ideal was to make safe progress through the first session, consolidate with minimal wicket loss during the afternoon, and then make hay when bowlers are foot-weary and frustrated as evening draws near.

That blueprint was never going to fit neatly when the most radical change to the scheduling of Test cricket in almost 140 years was instituted in 2015 — the advent of matches played in both daylight and floodlights, with a luminescent pink ball adding further to its novelty.

But while the performance of the pink ball remains a hotly debated topic among purists and progressives, the most fundamental change is being revealed as the tactics that teams employ to best utilise the altered ambient conditions to their advantage.

In its initial phase, day-night Test cricket had to conduct some strategic ploys that were previously known for exceptional circumstances only, such as rain-affected pitches (where batting orders were inverted) or overhead conditions that tempted captains to bowl when they might otherwise have batted.

In the second day-night Test that Australia hosted, against South Africa at Adelaide Oval in 2016, Proteas’ skipper Faf du Plessis foreclosed his team’s first innings so unexpectedly early to take advantage of night conditions that Australia opener David Warner was caught short, given he was off the field at the time.

Under cricket’s playing conditions, that meant Warner was unable to take his usual place at the head of the batting line-up when play resumed.

A year later, Australia skipper Steve Smith opted against enforcing the follow-on despite their 215-run lead over England and instead sent his own batters to face the shiny pink ball under lights, only to see wickets tumble and the state of the game change remarkably.

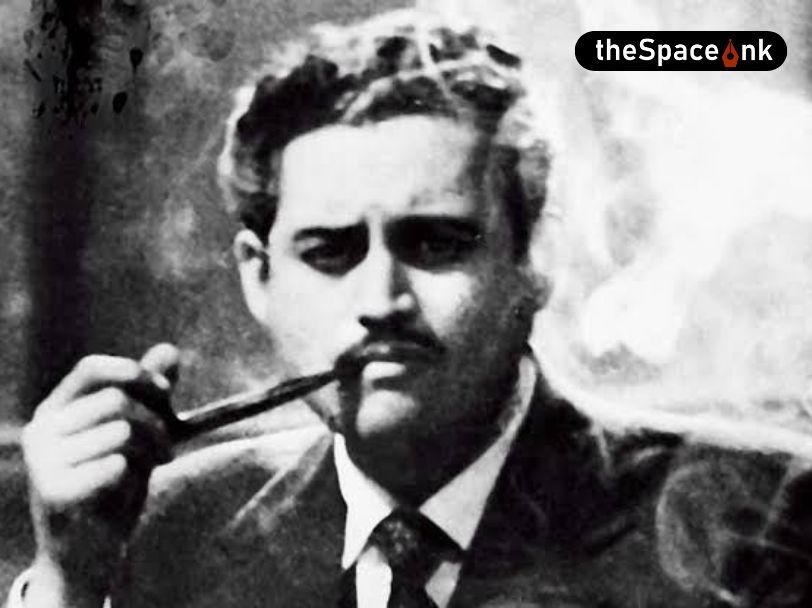

India finally made its debut in pink-ball cricket in November last year. The country’s first day-night Test match kicked off against Bangladesh at Kolkata’s Eden Gardens. BCCI president Sourav Ganguly (then newly appointed) was widely credited for ushering in the pink-ball system despite India’s resistance to it for four years as test viewership continued to witness a decline in India and elsewhere.

In comparison with the red-ball, the pink ball is lighter and tends to swing a lot more in the initial overs. Also, as is the case with the white ball, the pink cherry gets softer sooner and the swing vanishes way earlier when compared to its red counterpart. The spinners also seem to have difficulty in extracting as much turn from the pink ball as they do with the red.

The traditional red cricket ball has been used since 1877, and although different manufacturers’ balls behave a little differently, there hasn’t been a need to introduce a new ball until the Day-Night Test cricket arrived.

The primary difference between the red ball and pink ball is that unlike the former, to which grease is applied on the outer surface, the pigment is applied to the leather to make it pink. Even while in contact with the bat, the pink ball produces a ‘click’ sound rather than a ‘thud’ that comes from a red ball connected with the bat.

The buzz generated around the pink ball Test match in Kolkata has been immense. The manner in which the BCCI quickly geared up for the historic event, helped by the fact that the match was staged at the home ground of the board’s new president Sourav Ganguly, the enthusiasm with which the Cricket Association of Bengal took to the opportunity, and finally the passion with which Kolkata and its inimitable inhabitants owned the occasion is nothing short of spectacular.

But, as great a spectacle as this is, and what it is at the moment, its impact on Test cricket in the long run, and indeed its desirability, will only be revealed in time. If day-night Test cricket can genuinely bring in bigger audiences – more than 40,000 people turned up to watch the match against Bangladesh on the first day, unheard of for a Test in India in recent memory –and make the format more attractive to broadcasters, it can only be a good thing.

An undergraduate student of Sociology, Sloka is currently studying in Ambedkar University Delhi. He is passionate about topics related to Politics, Society, Sports and Pop Culture.