A truly postcolonial moment was made in the eastern quadrangle of Victoria Memorial on the evening of 23rd January 2021.

This Ministry of Culture event to mark the 125th birthday of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose may enter the annals for reasons not connected to the occasion. But there is little point in pondering on this for the moment. The winter sun had set by then. With the Prime Minister of India, the Governor of West Bengal, and the Chief Minister of West Bengal gracing the first row of the audience, a projection mapping show began.

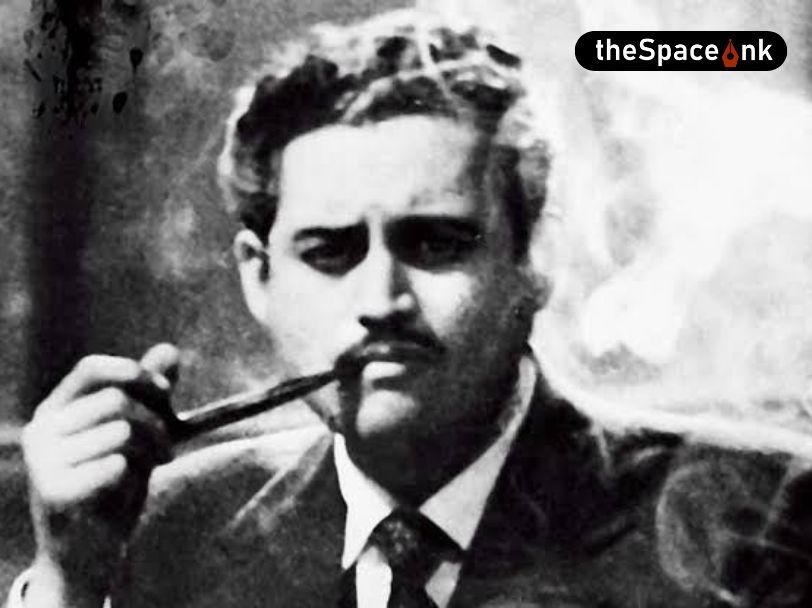

It was no ordinary son et lumiere show that we are used to. It was reaping a dividend from the cutting edge technology that fashioned it. As the digitally reconstructed images started splashing on the marble walls, towers and domes of the century-old colonial edifice and Bangla commentary and audio-dramatic capsules resonated in every nook and cranny of the VMH precincts, there came a moment of epiphany into the very third minute of the presentation. Netaji’s familiar face – complete with the army cap and the spectacles – was all over the best specimen of colonial architecture in the second city of British imperial rule.

As the audience broke into a rapturous applause, millions others following the show on digital platforms across the world must have felt a shiver running down their spine. Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose– who cared a least about a memorial erected to commemorate the passing away of the Empress of India and led a significant civil disobedience initiative to remove the Holwell Monument from the heart of the city – seemed to have stormed the final bastion of colonial rule.

It was a truly postcolonial moment.

It was also a sort of repositioning of the dominant image of a national hero who seemed to have lived and died in complete isolation in post-1947 India though the State narrative never did authenticate it. Back in the 1980s, Shyamal Basu, a biographer of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, authored Subhash Ghare Phere Nai (Subhash Never Returned Home). It topped the bestseller list for years, reaching tens and thousands of middle-class Bengali homes in the process. This postcolonial moment apparently succeeded to upset that mindset. It also succeeded in bringing the smile back to the lips of a section of Bengali populace – hitherto extremely influential and of little significance in recent years – known as bhadralok.

With the election to the Assembly of West Bengal round the corner, two eminent representatives of bhadralok seem to be hogging all the limelight – Rabindranath Tagore and Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose. Rabindranath – Gurudev to many – is being quoted in every major public meeting with such fluency and conviction, that a rank outsider might start believing that Rabindranath is running all the parties irrespective of their ideological positions – left, right and centre! Every road is leading to Santiniketan these days and the Visva-Bharati is making headlines for reasons remotely connected to academic and artistic excellence.

The Rabindranath narrative even reached the Parliament during the budget session. The Home Minister was said to have ruffled many a feather when he sat signing the visitor’s book placed at Udayan, a Rabindranath residence maintained by the Visva-Bharati. Many, including the leader of the second largest party in the present Lok Sabha raised serious concerns about the alleged breach of sanctity of Gurudev’s chair. The Visva-Bharati Vice-Chancellor had to issue a clarification note to allay such fears. The note has since gone public and viral over the social media.

As far Netaji is concerned, there were rumours that the Victoria Memorial might well be rechristened after him. Cultural erasers backed by political ambitions often cause havocs. However, the rumours were soon mitigated. Only the century-old Kalka Mail was named Netaji Express and all the youth hostels are all set to bear his name. The Prime Minister has suddenly found an early exponent of ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ in him. The State government, on the other hand, rose to the occasion by sanctioning rupees 100 crore each to install an Azad Hind Memorial in New Town, and construction of Jai Hind Bhavan in every district. The Rabindra Sadans and Rabindra Bhavans – custodians of Indian culture in postcolonial times – are sure to face some competition. Most significantly, the Kolkata Police – which always ran after Netaji while he was alive – is getting a Netaji Battalion very soon.

Every road is leading to Santiniketan these days and the Visva-Bharati is making headlines for reasons remotely connected to academic and artistic excellence.

These are tell-tale signs. They have greater political ramifications, for sure. One must also remember that names like Chaitanya, Birsa Munda, Titumir, Ishwar Chandra Vidysagar, Swami Vivekananda, Harichand Thakur, Syama Prasad Mookerjee are also going rounds in various quarters. Community aspirations are being funnelled through such names. The icons. For the hour of the icons has arrived. The elections – usually fought over economic and social issues – are being fought over exclusive rights to own the icons with Rabindranath and Netaji stealing the march over all others.

There is no denying that we Bengalis are fond of our icons. Construction of icons is always problematic. It is intrinsically linked to political will and invariably motivated by a process of exclusion. But we care the least about such nitty-gritty, and never tire of our icons. We love to bask in their reflected glory, often to hide the not-so-optimistic present, but also to draw inspiration from their deeds and thoughts.

Things took a backseat over the last couple of decades. Before the Communist Party took over the reign, the Chairman of the People’s Republic of China did have a sizeable following. The Left party offices hardly had a Bengali face on their walls until Jyoti Basu breathed his last. Thus, in spite of early morning processions on ‘Pachishe Boishakh’[1] and 23rd January[2], both Rabindranath and Netaji failed to move the corridors of power. Since identity politics became a vogue and voters were segregated along their belief-lines, other names started popping up more often.

No longer. Now that both the ruling and the opposition parties have realized the potential of Rabindranath and Netaji as pan-Bengal icons, the next few decades look poised for more and more attention on them. Whether that would translate into a resurgence for Bengal is another question altogether.

Footnotes:

1.Rabindranath Tagore was born on the 25th of Boishakh as per the Bengali calendar

2.Subhash Chandra Bose was born on 23rd January

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons, PTI

Anshuman Bhowmick is a cultural commentator based in Calcutta aka Kolkata. Among many other things, he reviews theatre for a leading English daily and a prominent Bengali periodical and represents Bengali theatre in national and international forums. A widely travelled man equally at home in West Bengal and Bangladesh, Anshuman is curious about everything related to Bengal - past, present and future.