(Diaspora)

Part 1

It was at a Christmas party in 2019 when I got a strong impression about him. The party was held at a night junior high school, and he was one of the foreign students there. He was called Bikas, the son of a Nepali laborer and said to be 15 years old. I taught them once a week and worked as an interpreter as well. (Diaspora)

The school is administered by the local government specifically for those who missed the opportunity at formal education for various reasons. Therefore, most students are adults. Bikas was the youngest, although he looked much older than the age he claimed. (Diaspora)

“Fifteen years old!?”

Surprised, I asked him if he was sure, and he smiled bashfully. (Diaspora)

From the 1950’s to the 1960’s, there were many middle-aged Japanese who were unable to attend school due to poverty, although the Japanese economy started growing rapidly in the latter half of the 1950’s. Also, after the normalization of diplomatic relations between Japan and China in 1972, the Japanese orphans who were left in China after the Second World War were repatriated to Japan and enrolled in the night schools to learn the national language of their long-estranged home country, Japan, as well as other subjects such as its geography or history. When I started working at the one in Osaka, I met a few repatriates who appeared to be older than I am. (Diaspora)

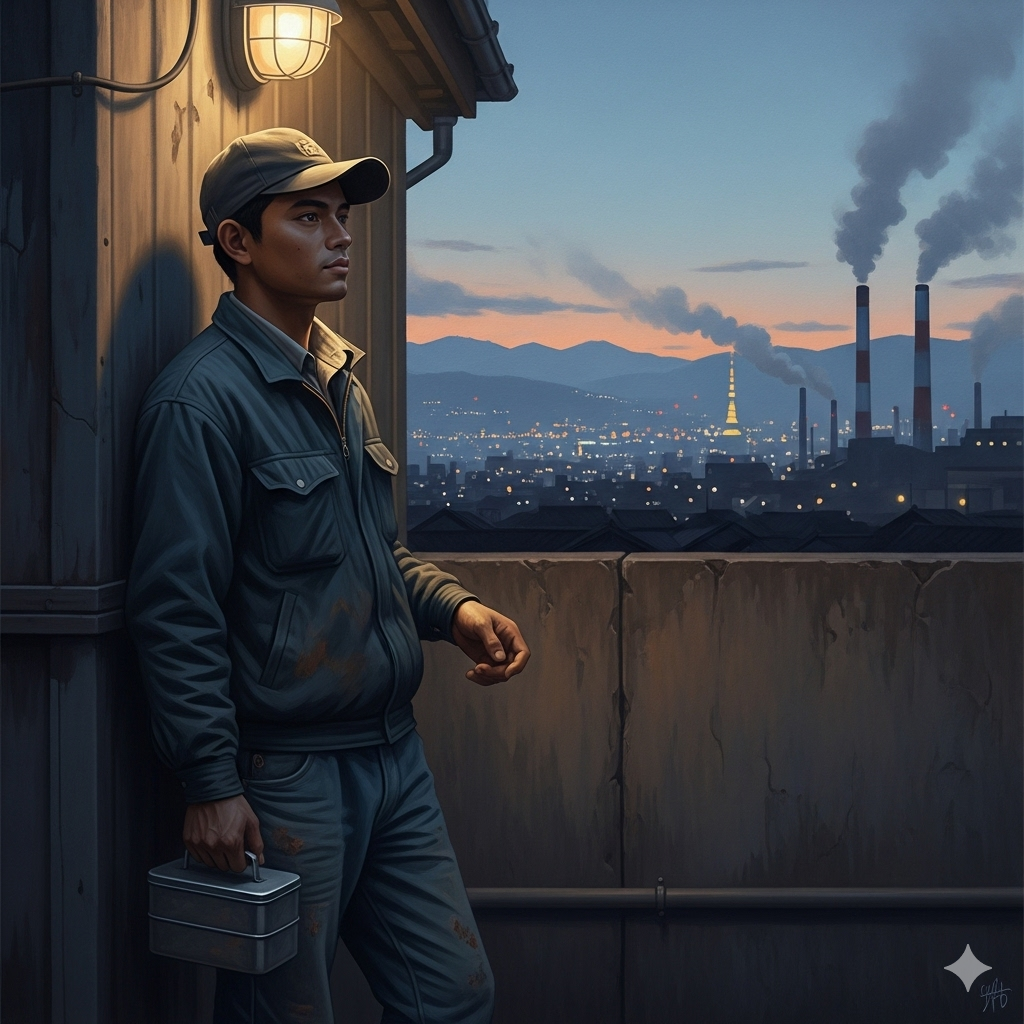

There are many foreign students now. Beginning in the 1980’s, as the population of migrant laborer grew, children in their late teens and early twenties began to enroll in the government-run night high schools—and the number of enrollees increased significantly in the late 1980’s. They entered Japan on dependent visa, in order to work to help support their families. Dependent visa holders are allowed to work for 28 hours per week according to the Japanese immigration law, provided they are 16 years old and above. (Diaspora)

“When he noticed me, he slowly approached me to say that he wanted some vegetables too. All that was left were some radish leaves from the pile just a moment ago.”

Along with this, they attend a local night high school for the sole purpose of learning the language because Japanese language schools are expensive. Bikas was the only student who was not eligible for part-time work. So, he had been counting down the days until his sixteenth birthday. (Diaspora)

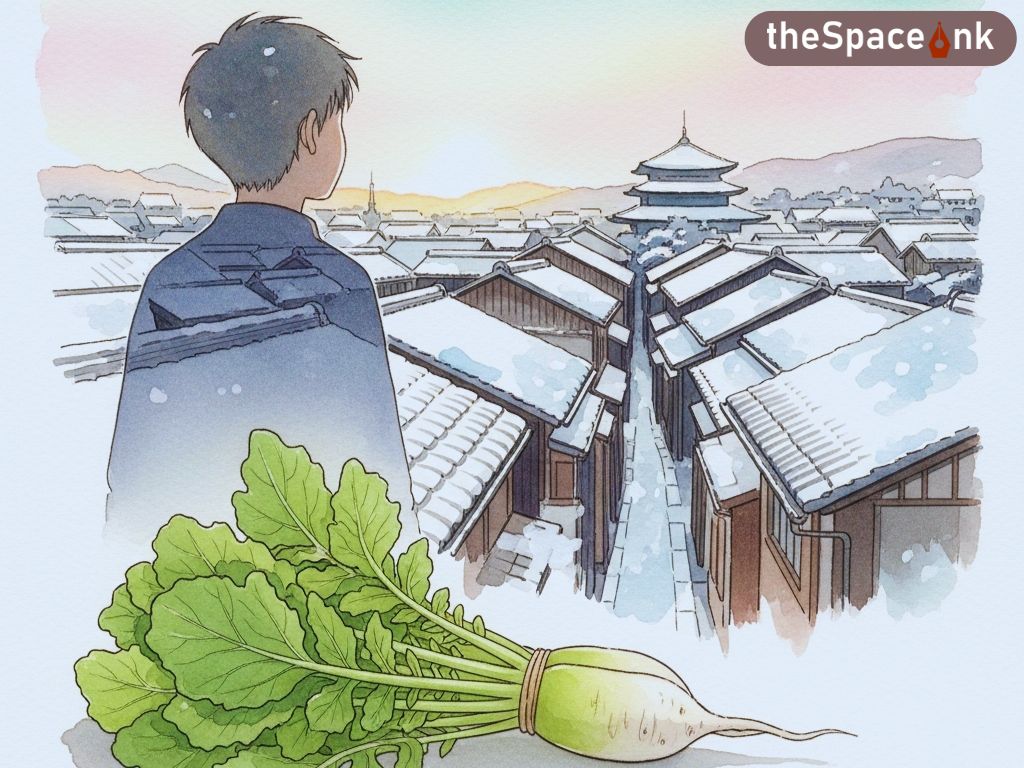

The party started with modest meals, followed by a game where teachers and other staff members distributed the Christmas gifts they had prepared. Fresh vegetables, donated by a neighboring farmer, were lined up at the back of the classroom. At the end of the day, it was announced that everyone could take some freely. Immediately, the students rushed and grabbed the vegetables, then headed home. It was a whirlwind event. (Diaspora)

Once things had calmed down, I glanced at the corner of the classroom and saw Bikas standing there empty-handed. When he noticed me, he slowly approached me to say that he wanted some vegetables too. All that was left were some radish leaves from the pile just a moment ago. (Diaspora)

“In January, I heard that Bikas was supposed to move to another city due to some reasons which nobody knew. “He might be unable to continue his studies,” a teacher said to me sadly.”

“May I take them?”

He asked as if he needed my permission.

“I’m so sorry, but there are no vegetables left.”

I replied with an apology.

“I’ll have them.”

He beamed at radish leaves and carefully cradled them in both hands.

It was a cold winter night but he wasn’t even wearing socks. (Diaspora)

In January, I heard that Bikas was supposed to move to another city due to some reasons which nobody knew. “He might be unable to continue his studies,” a teacher said to me sadly. (Diaspora)

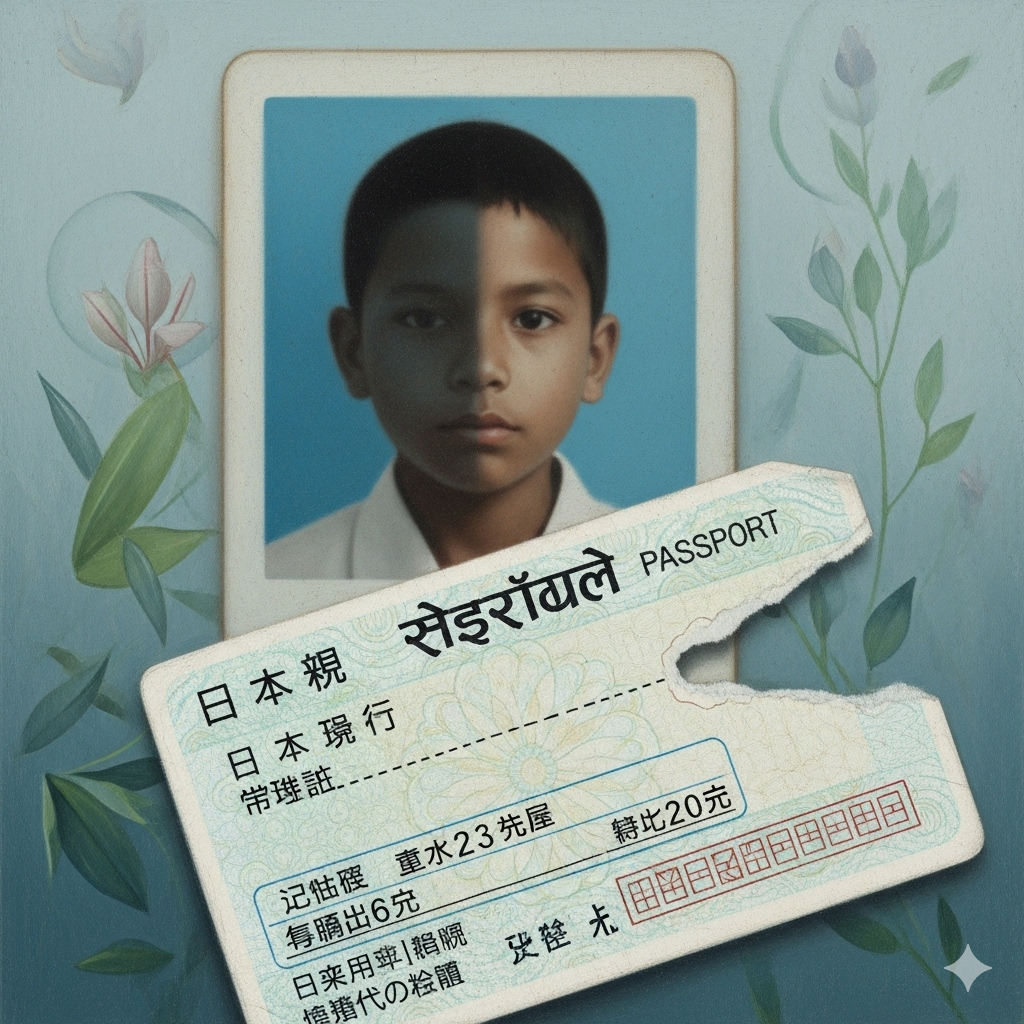

I remembered the essay he had contributed to the school’s literary magazine. He shared how he got his visa to Japan in the eighth grade, how he went to school only once a week when he first arrived, and how happy he was to be able to study every day after coming to Osaka. Near the end, just before conveying his gratitude to every teacher, he wrote, “I want to keep going to school forever, but no one knows what the future holds.” His premonition had come true. In those days, there were few night high schools in Japan. Due to the lack of budget and public understanding, only several cities had them. (Diaspora)

Also Read: LET’S RECLAIM THE WORLD

Leading up to his move to another place, one day, he asked us how he could get his own visa—not a dependent visa—because he wanted to “stand on his own feet.” We advised him to master the language first; otherwise, we told him, “it’s almost impossible to stand on your own feet.” Then, he left the school. (Diaspora)

Part 2

Several months later, I was requested to interpret at a public prosecutor’s office. I worked as a legal interpreter, too, whenever needed. It was a case of domestic violence between a Nepali husband and wife. The prosecutor interviewed the victim: the wife. (Diaspora)

“Since the status of “brother” does not qualify for a dependent visa, he falsified his brother’s familial relation and age. Then, he made his brother pretend to be his son. I was stunned when I saw his younger brother’s name and photo. That was Bikas.”

I wondered how the case came to light. Usually, people in their situation don’t disclose family troubles because their visas could be cancelled if things escalate into a serious criminal case. But what astonished me the most was that she spilled her husband’s secret to the prosecutor. (Diaspora)

She was his second wife. And she revealed that his 15-year-old child with his first wife, whom he had brought to Japan, was actually not his son but his younger brother. Since the status of “brother” does not qualify for a dependent visa, he falsified his brother’s familial relation and age. Then, he made his brother pretend to be his son. I was stunned when I saw his younger brother’s name and photo. That was Bikas. (Diaspora)

In the practice of judicial interpretation, if it is discovered that the interpreter knows personally any of the parties involved in the case, he or she shall be prohibited from serving as an interpreter. I told the prosecutor that I knew Bikas. (Diaspora)

When I saw the photo, I was taken aback and exclaimed, “Bikas!” But Manoj rebutted me on the name of his uncle, “No, He’s Narayan.”

Part 3

A few years had passed since then. I worked at another senior high school as a Nepali language teacher for Nepali students. They made up the largest group among the foreign students. All of them were children of migrant workers who were all, without exception, curry restaurant cooks. Compared with the students at night junior high schools, they were relatively fortunate. They could study during the day and would be given a senior high school diploma. This meant they would become qualified to apply for colleges and universities, enabling them to climb the social and economic ladder. There were nearly 20 Nepali students in the school. Manoj was one of them. (Diaspora)

One day, when I told him that I lived in Kyoto, he showed me a photo of his uncle saved in his mobile phone. He said he was working at a factory in the outskirts of Kyoto prefecture. When I saw the photo, I was taken aback and exclaimed, “Bikas!” But Manoj rebutted me on the name of his uncle, “No, He’s Narayan.” On the spur of the moment, I figured there was some kind of situation. The event at the prosecutor’s office came to mind. So, I didn’t push it any further. Tactfully, I played along to keep our conversation going. (Diaspora)

“Until now, I have no idea about his real identity. Still, the scenes I witnessed that Christmas night about half a decade ago are etched in my memory, never to fade.”

Another two years passed. Manoj was about to graduate and start working; meanwhile, his younger sister was due to enroll in the school. He asked me to keep an eye on his sister in case Nepali boys bullied her at school. In reply I asked, (Diaspora)

“By the way, how is your uncle Narayan?”

“Thaha chhaina. (I don’t know.)”

His blunt response made it seem as if he were asked about someone entirely unrelated. Yet, I couldn’t resist pushing him further and continued asking questions.

“Is he still in Japan or back in Nepal? What is he doing now?”

“Khabar chhaina. (Haven’t heard anything.)”

He replied curtly. The tone of his voice was completely devoid of any sign of concern.

Hello, Bikas. Or …Narayan?

Who on earth are you?

Is there anybody who cares for you? (Diaspora)

Also Read: Spring Blossoms in the City

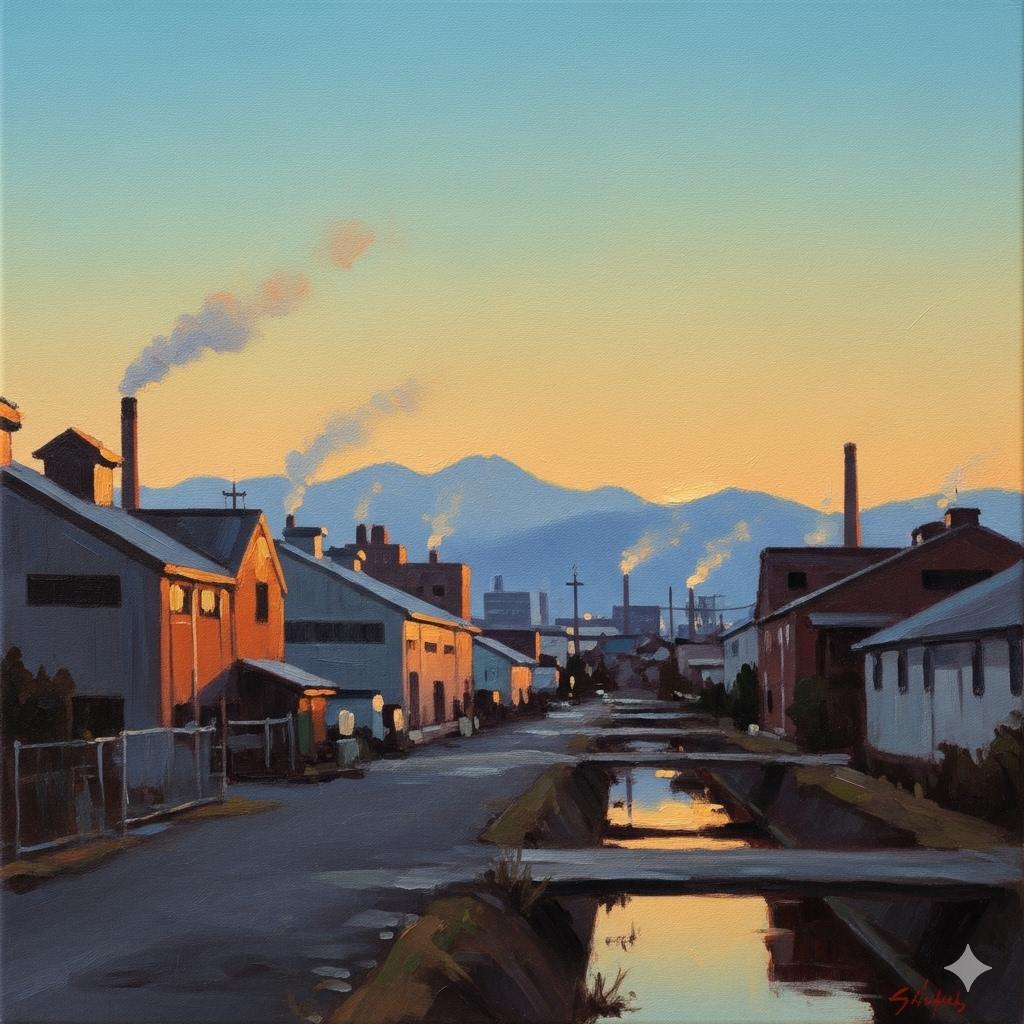

Until now, I have no idea about his real identity. Still, the scenes I witnessed that Christmas night about half a decade ago are etched in my memory, never to fade. Those appeared to me like two beautiful pictures, portraying a Nepali boy rendered in pastel colours with a very subtle, delicate touch: In one, he stands alone, barefoot and empty-handed, in the deserted silence of the classroom after all the other students had gone home. In the other, he looks contented, a smile on his face as he twines a bunch of radish leaves in both hands. (Diaspora)

Image Courtesy: AI

Mayumi Yamamoto is a writer and academic based in Kyoto, Japan. Her poems have appeared in Literary Yard, and some opinions in Indian Periodical. She authored several published books in the Japanese language.