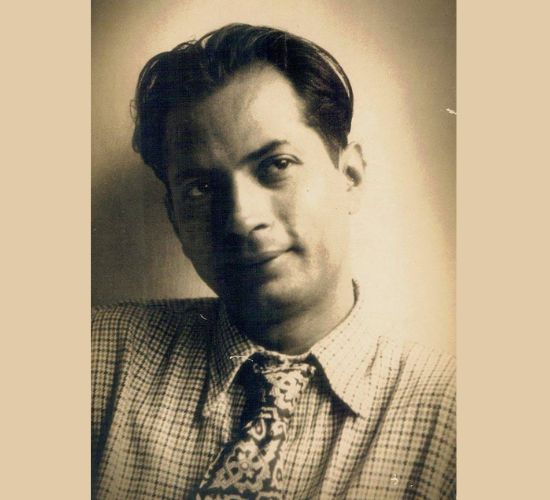

Bimal Chandra Roy was born on 12 July 1909 in Suapur village, now in Bangladesh. The fourth of seven brothers, Bimal Roy belonged to a family of aristocratic zamindars. The affluence of the family in those days placed leisure above hard work. Roy began his education at home till he went to Dhaka, coming home to spend his holidays in the village. Since he was a boy, Roy was an avid photographer. He took up science as his specialisation after high school. A little-known fact about him is that Bimal Roy did female roles in plays like Misar Kumari. These were pleasant boat journeys across rivers, offering an original audiovisual landscape that found their reflection in many of his films[1]. However, his father’s demise was followed by economic disruption, which made everyone look out for a means of living. The estate manager is said to have thrown him and his family out of the family home upon the death of Bimal Roy’s father. They made their way to Calcutta, among the many migrants who, in twentieth-century India, have undertaken a similar journey.

By the end of 1930, all the seven brothers had migrated to Calcutta. A business in transport set back the family into better days while some of the brothers joined British firms. But Roy’s interest in photography on the one hand and cinema on the other, would often take him on long walks towards the film studios at Tollygunge. His pursuit for a career in films finally landed him a job with New Theatres first as an apprentice and then as assistant cameraman. From assisting Nitin Bose as cameraman, Bimal Roy became a senior cameraman for Pramathesh Chandra Barua for the Hindi version of Devdas.

Bimal Roy started working as an assistant cameraman and cameraman on documentaries in 1932-33, but his foray into cinema effectively commenced when he was hired as a publicity photographer by Pramathesh Chandra Barua, whose Devdas (1935) would become a landmark film. At Calcutta’s famous New Theatres, which helped to define cinema for a bhadralok audience, Roy was engaged as an assistant to cameraman Nitin Bose where he soon won a reputation for his command over lighting and composition. He worked on close to ten films as a cameraman before venturing forth as a director with his film, Udayer Pathey (1944, Bengali; remade in Hindi as Humrahi, 1945), which in many ways echoes the aesthetic, moral, and political sensibility so strongly on display in his films of the 1950s.

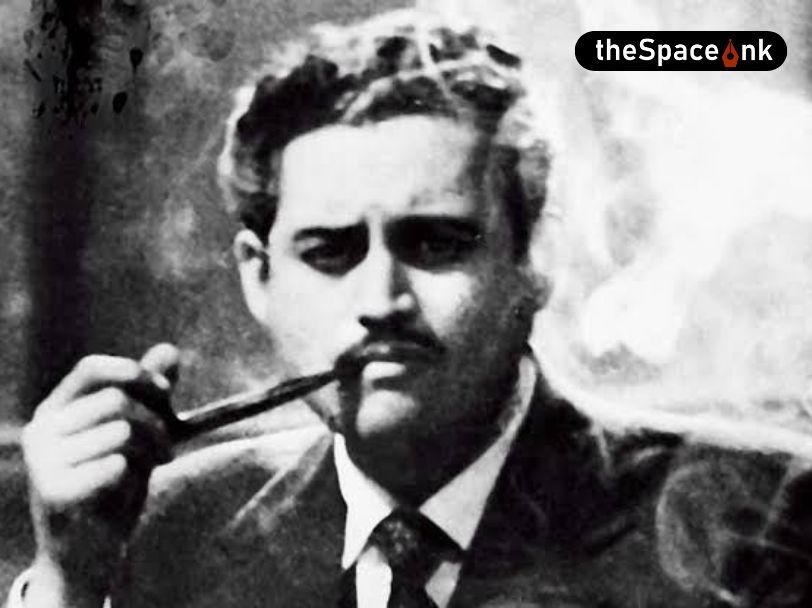

The collapse of New Theatres, the pressures of World War II and the advent of Bombay cinema heralded a new phase in the life of Bimal Roy. His own migration to Bombay, one might say with a touch of exaggeration, precipitated his understanding of the migration from rural areas to urban centres as one of the great social phenomena of independent India. Bimal Roy’s social sensibility and humanity are palpably on display in this superb film, which won him many international accolades[2].

After more than three decades in films, Bimal Roy passed away in his Bandra bungalow in January 1966. He was suffering from lung cancer. His banner, Bimal Roy Productions, was already teetering under a burden of heavy debts incurred during his illness and following the fire at Mohan Studios that left almost everything in cinders, limped for a while and then stopped. Do Dooni Char was completed and released after his death but tanked at the box office.

The cinema of Bimal Roy embraces much more than the images we see on screen shot and projected on 35 mm which might have become a fossilized symbol of the past. The “great four – Mehboob, Bimal Roy, Guru Dutt, and Raj Kapoor”, made the major films of the 50s. These directors had seen the traumatic years in their formative years, the 30’s and 40’s that encompassed major events in the sub-continent: the struggle for Independence, famines, changing social mores, the global fight against fascism, etc. All these events shaped their ethos and vision.

Bimal Roy’s cinema is known for its powerful storylines, technical finesse and some subtle and not-so-subtle social messages that emerge from the very act of storytelling and the process of filmmaking. But what we seem to have missed out on is the core of displacement that defines his cinema almost from beginning to end. He was himself a displaced person who had to migrate from a village in Suapur distanced from the noisy city of Kolkata distanced culturally, politically and historically from his roots. His displacement and migration happened in the 1930s when India was still under British rule and the political realities were different from what evolved later. He was an unwitting participant in this process of transition though his cinema or his selection of stories and scripts for his films do not reflect any lament on this displacement which also suggests that he perhaps accepted it as part of his life and coped with the changed circumstances of his life and work as they kept changing from time to time, place to place and so on.

An unforgettable quality of Bimal Roy’s entire range of films lies in its extra-cinematic perceptions. A closer study offers an insight into his oeuvre that stands out distinctly for the films’ extra-cinematic perceptions, never mind whether they were derived from or adaptations from literature or are developed from a created screenplay independent of any literary origin. His stylistic figurations partly stem from the social and political environment that shaped him, when he grew up in Dhaka, then shifted to Calcutta, joined New Theatres, looked at the world outside through the lens of his camera and also with his insightful eye both of which combined to create a third dimension which in turn, spilled over into his films. All these elements came together when he arrived in Bombay to make Hindi films having little knowledge or command over the language.

Bimal Roy’s cinema is known for its powerful storylines, technical finesse and some subtle and not-so-subtle social messages that emerge from the very act of storytelling and the process of filmmaking. But what we seem to have missed out on is the core of displacement that defines his cinema almost from beginning to end.

The concept of ‘homelessness’ described so lucidly by Ranjani Mazumdar[3] in her seminal essay does not apply to the “outsider” as interpreted in and through the characters in the cinema of Bimal Roy. “Homelessness” does not characterize men and women like Devdas in Devdas, or Lalita in Parineeta or Kalyani in Bandini or Sujata in Sujata. These characters are not homeless. They either do not really belong to the “home” they are brought up in, such as Sujata and Lalita, or try to move out to seek something else in spaces other than their ‘home’ such as Devdas. Mazumdar cites examples of homelessness from films made at a much later date decades after the Bimal Roy phase was over and the entire ideology of occupying or coming to occupy or moving out and in from old to new spaces had manifested itself differently in the cinema of the kind she has elaborated on.

The outstanding thing about his cinema is that one cannot mark his work with the slightest sign of a conflict of interest between honesty and aesthetics, between ideology and reward and between commitment and fame. His choice was clear as evinced in his oeuvre – it was honest aesthetics, ideology overshadowed all thoughts of reward, fame followed commitment and it was not the other way round. The beginnings of the negative impact of industrialization on the rural poor came to the surface in Do Bigha Zamin which offers a different slice of Kolkata where Bihar and UP migrants live shoulder-to-shoulder with the local Bengali urban poor. This clearly goes to show that his views on industrialization and modernization made his realization of the exploitation of the marginal and the oppressed more acute than ever before.

Images courtesy: Shoma A. Chatterji

Notes:

Rangoonwalla, F.: Life and Work – Bimal Roy – A Critical Study, NFAI, 1991.

Lal, Vinay: Bimal Roy, https://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/southasia/Culture/Cinema/bimalroy.htm,2008.

Mazumdar, Ranjani (2001) ‘Figure of the tapori: language, gesture and the cinematic city’, Economic and Political Weekly, December 29: 4972–4880.

Shoma A. Chatterji is a freelance journalist, film scholar and author based in Kolkata. She has won the National Award twice, in 1991 and 2000. She has authored 26 published titles of which 14 are on different areas of Indian cinema. She holds two Masters Degrees and a Ph.D. in History (Indian Cinema). She has also won a few Lifetime Achievement Awards from different organizations over time.

One Response

Good write , an independent understanding of Bimal roy