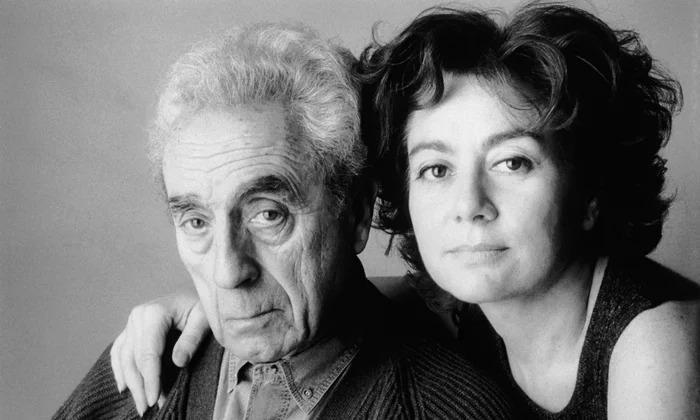

We would probably start at the beginning with these photographs of Michelangelo Antonioni.

All of 82 and impaired by a stroke, the maestro had nevertheless turned up as the honoured guest of the Indian International Film Festival at Kolkata in November 1994. Still the dapper man that he had always been, he easily commanded the attention of the throng at his reception at the Crystal Room of the Taj Bengal Hotel that evening.

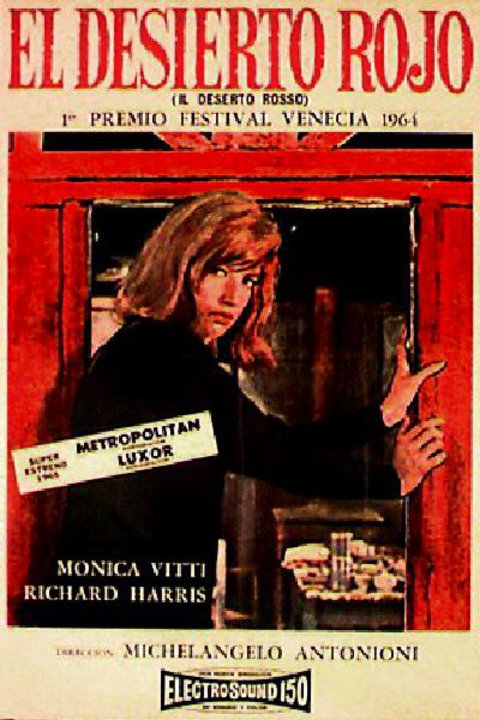

His adoring wife Enrica by his side, he was being gently steered around in his wheelchair as film personalities stood all at once to pay tribute to the creator of ‘The Night’, The Eclipse’, ‘The adventure’, ‘Red Desert’, ‘Blow up’ and ‘The passenger’. He moved slowly in silence, occasionally acknowledging a smile with a smile.

Did he look sad or sombre? I doubt it; the least that I can remember of watching Antonioni that evening from a reasonable distance. He rather looked charmed watching a crowd gathered to watch him. His soft nod as the Indian director, Aparna Sen bowed close by his chair and said, “I am filmmaker’, is still etched in my memory.

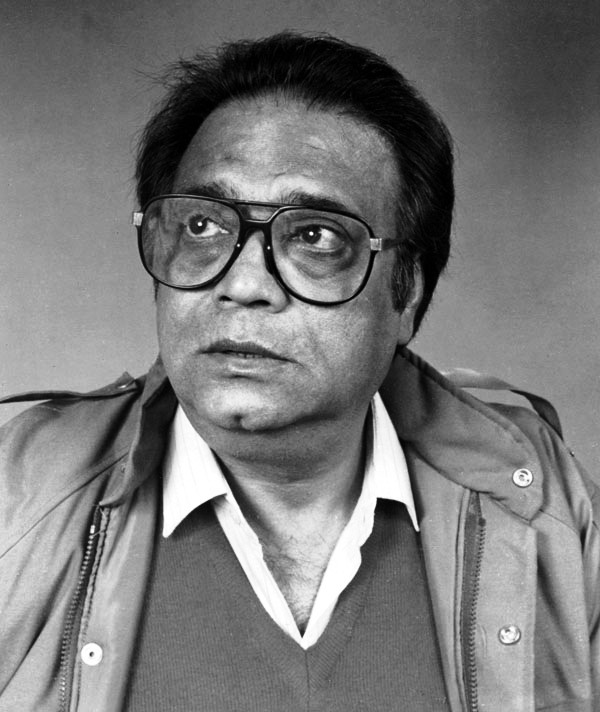

Honestly, he looked every bit the philosopher that he was but never paraded himself to us. Somewhat reminding onlookers of Stephen Hawking strapped to the wheelchair but exquisitely free in the mind to roam the expanding universe. Antonioni was carrying his world with him to meet other worlds. He had just been taken around a gallery of photographs on the life and works of Satyajit Ray, all of it culled from a lifetime’s labour of Nemai Ghosh. And he had wanted to meet Ray’s Boswell.

Nemai met the maestro the next morning picking up some beautiful moments of the couple’s togetherness. Antonioni asked Nemai to be his still photographer if and when he returned to make a film in India.

That film never happened but a correspondence developed between the maestro and Nemai, culminating in a warm invite to a retrospective of not his films but paintings to mark his 94th birthday!

Nemai in his reply, however, had his request registered that he be allowed to photograph the maestro at his easel—the request being granted, the pictures of the morning of 30 September 2006, happened at Via V. Tiberio, Rome. These were to follow the extensive photographs at Comune di Roma 28 and 29 September when Antonioni was overseeing the display of his works and then attending the grand opening of his retrospective.

That retrospective bore, suggestively and memorably, the title ‘Silence in Colour’.

There is a clear mixture of light and shade, studio and open space in Nemai’s studies of Antonioni at the easel. They look like stills from his own films, where the actors do not speak enough, and the forms silently coordinate to create thought. Often these thoughts are built around absence, anxiety, loneliness and silence.

The soft September morning light nearly replicates the magic hour of dusk and slowly over the four hours of the shooting Antonioni and his painting, his window on the Tiber, the table lamp overhead and the surrounding, non-invasive darkness of the studio turned into the soul and body of yet another painting—drawn, framed and held by a camera.

As we admire the painting, like the photographs of Antionioni by Nemai Ghosh, we gradually move into a territory long claimed and charted by the maestro when he introduced into his painting process the power and beauty of the camera. As early as 1985 he had explained the process thus…

“Sometimes they (images of mountains) are tiny. I paint them with a very fine brush using a lens. Then I photograph them, and I make successive enlargements. The result is almost always a surprise, a bit like firing pottery. Sometimes I change the colours during the printing or make enlargements up to two metres across or even reduce the enlargement, if I think that it will look better. Many details are so small that they are invisible to the naked eye. Thus, the subject matter of the painting, the meaning of what I am trying to do, is only revealed through the enlargement process.”

Also Read: An Ode to Manoj Mitra’s Theatrical Brilliance

Revealing a meaning through enlargement is, to Antonioni, also a recreation of reality like he mentioned in 1964 that underneath the revealed image there exists another image more faithful to reality and then another beneath it, and then a further image beneath the previous one. These successive revelations and their corresponding realities and mysteries, he accepts as his main problem in his soon to be made film, ‘Blow Up’ (1966) which is to recreate reality in an abstract form. His aim, he stated while still filming the movie, was to question ‘the reality of our experience’. A brief recap of the story of ‘Blow Up’ will help.

The photographer-hero Thomas is bemused by some enlargements of photograph he had chanced on in a London park. They provide a distant view of a couple embracing. The girl had caught him snapping and demanded that he hand over the roll, which Thomas, well within his rights, refuses.

Studying the enlargements, Thomas is struck by the way the girl’s head is turned away from her lover in one of them. Running his finger along the line of her look Thomas discovers a hedge. By blowing up a portion of the hedge he gets to a tiny white blob. Another twelve-by-fifteen enlargement of the blob reveals a hand holding a gun to shoot.

The revelation of the gun in the enlargement triggers off the process—the search and discovery of the murder. Meanwhile the girl in the park turns up in Thomas’ studio to offer her body in exchange for the negatives.

On discovering the body in the park, Thomas then goes around town in futile search for the girl only to return to the park to find the corpse! From the park he returns to the studio and discovers all the photographic evidence gone, leaving him with more questions than he can even begin to answer.

Also Read: Death and Departure: Meeting Dom Moraes

Magnification of portions of two of the images had caused Thomas to believe that he was actually discerning a gunman and a corpse. The ‘objectivity’ of this conclusion, avers Mathilde Nardelli, is not quite confirmed in the film, as not only is the final blow-up with the victims’ body extremely grainy and almost abstract, but the fact of the murder itself is left unresolved as the story unfolds.

In his ‘existential’ Seymour Chatman had argued in ‘Antonioni, or The Surface of the World’ that the film also shows how photography’s “visual records’ are liable to being used ‘fictitiously’. Thomas’s examination of these pictures builds a story out of them. It is as much a construction as a reconstruction of the events. The Russian semiotician Jurij Lotman has drawn our attention to the ‘textuality’ of pictures and the way “Blow Up’ highlights how even a single photograph is always already a text, an interpretation.

When Antonioni mentioned that his aim in “Blow Up’ was to question ‘The reality of our experience’ he was hinting at an observer’s ability or inability to perceive the correct value of things.

While close to wrapping up filming, he had confessed, “Frankly, I’m not sure yet about what I’m doing, because I’m still caught in the ‘secret’ of the film.”

So, in search of this ‘secret’, i.e., layers of meaning beneath layers of previous meaning he says he had actually put himself in the protagonist’s shoes in the moment he discovers the body. He had stopped in the shade of an English lawn; paused in the park, gazed at the mysterious clarity of London’s billboards. He had approached the imaginary corpse and totally identified with the photographer. He felt his excitement, his feelings, the thousands of perceptions his ‘hero’ felt as he stood by the corpse. And then, he had also experienced his coming back to sensers, his thoughts, his reactions. All this must have lasted no longer than a few minutes, one or two. When the rest of the cast joined him, all his inspiration, all his sensations had disappeared.

In 1964, when he was working his way into the thesis of “Blow Up’—that meanings only conceal other meanings—he had concluded with alarming alacrity:

“Until you reach the true image of the absolute and mysterious reality which no one will ever see, or may be until all images or realities disintegrate, there is a reason for the existence of abstract cinema.”

It now seems reasonable to interrogate that from a growing urgency to address emerging meanings and inescapable abstractions or challenge his pictorial imagination. Antonioni took to painting in the mid-70s as a serious parallel activity to his filmmaking. He, who had painted since in his prime but never considered himself a painter or his work with lines, colour and space more than ‘doodling’, suddenly found the canvas dissolving into the silver screed vice versa.

It was the commencement not merely of new experiments but of a new way of life. A style of work and living Antonioni never gave up till the end. And so, he created on his return to painting, the series called “The Enchanted Mountains” which was presented successively in Venice, Rome, Paris and Ferrera. These are photo enlargements—blow-ups, if you please—from small paintings using widely disparate colours, techniques and materials. The mountains have found home in the Antonioni Museum in Ferrara since 1995.

There were four such (all composed between 2005 and 2006) in ‘Silence in Colour’ when Nemai Ghosh followed the maestro in his wheelchair from wall to wall, corner to corner, mount to mount. It caused Nemai to feel that his subject was witnessing not a curation of his paintings from different times but a reeling off of his autobiography in hitherto unmade movies. Nemai was yet to observe Autonioni in his studio (that happened two days later) drawing silence in black on white with utmost caution.

The silence in the room, he felt, was an add-on to the silence of the piece. Which when filled with colour by his assistants, Alessandra and Monica, (they describe themselves as just a paintbrush, a tool’) can acquire a voice and speech. Like they do in ‘Nero e Oro’ (Black and Gold), ‘Verde sull’oro’ (Green on Gold), ‘Rubans Chinois’ (Chinese Ribbon), ‘2 Colori’ (2 Colours) ‘Tiffany’ (Tiffany), ‘Caleidoscopio’ (Kaleidoscope) or even ‘Il Segno’ (A sign). Speech apart, there is music to be heard in the festivity of design, architecture and colour. Yet all that the maestro wanted to construct, see and listen to in these forms and colours was silence. There is a small and a big history to this.

The shorter history relates to the execution of the paintings since the stroke reduced the maestro’s speech to almost inaudible whispers but spared his left arm enough to be able to trace lines, squiggle amazing patterns, forms and statements. It became as it were his speech synthesizer to communicate with the world.

Monica speaks of his sure and simple gestures—his sleight of hand, eventually—to instruct, indicate colour and show movement. Like a fusionist he reveals curves, lines, forms and colour which seem to have been already there on the canvas, invisible to those around and waiting to be uncovered. The title of the retrospective, no matter how musical the content, is a tribute to these endless hours of gesture. One is reminded of an expression from Seamus Heaney’s poem— ‘acoustics of snow’.

The longer history reaches back to his youth when he found that making cinema offered him the chance to express himself, communicate with the rest of the world. To a question by Andre S. Labarthe for Cahiers du Cinema in 1960— ‘What would you do if you no longer made films?’—he had replied, “Since I’m not a good communicator, without my camera I would have the feeling of being non-existent.”

Also Read: Hrishikesh Mukherjee- A Titan in Indian Cinema

He then proceeded to explain further, “Other jobs that I could have carried out are architecture and painting in that order. As a child I didn’t design puppets like most kids of my age; I drew doorways, capitals, plans of amazing castles. I built city districts in cardboard and painted them with wild colours. I have always loved colours. The few times that I dream, I dream in colour. The first thing that strikes me in a face is its colour. I don’t say so to make myself special, it’s simply a trait of mine like any other. I am naturally very impatient to make a film in colour.”

That film turned out to be ‘Red Desert’, made in 1964. But the preparation for this film had begun way back in his late teens when he did portraits and a good deal of architectural drawings, both of which fascinated him. Imagining tones and colours of faces posed challenges to his study of faces. Like the camera, paint has always been a tool for him to inscribe meaning. For years till those inspired periods in the mid-70s, his painting had silently bided it’s time to resurface on canvas.

Preoccupation with his cinema turned his secret passion for painting into a medium-specific culture, transferring all the labours of putting forms on canvas to mapping and situating images within a camera frame. Colour being an abiding concern, Antonioni did most of his colour adjustments during shootings and told Jean-Luc Godard in an interview, “I never rely on the possibilities of a developing lap when I’m shooting. I try to give objects and landscapes the colour I want on location, so I don’t have to do any work in post-production. The only use I make of the lab is make sure that the effects come out as originally intended.”

In a direct reference to ‘Red Desert’ Godard had posed a question to Antonioni that all the admirers of the maestros’ paintings would have loved to ask him sometime or the other, or after looking at one of his colour films or the other.

The simple and straight question was: When you start or end a shot of an abstract shape, of an object or detail, do you do it with the same spirit of a painter?

The answer was: “I have a need of expressing reality in terms that aren’t completely realistic. For instance, the white abstract line that breaks into the shot of the little grey street certainly captures my interest more than the car driving towards us. It’s a way of getting close to the character by starting from things instead of her life, which I don’t see as particularly relevant.”

This obsession with colourfully photographing stillness and silence within a moving image became the maestro’s signature ‘Red Desert’ onwards, extending to “Blow Up’ and climaxing in the final seven-minute sequence in “Passenger’ that has become a classic of film history. It isn’t so difficult to spot a connection between his return to actual painting and embarking on one of the most ambitious long shots to depict a silent death scene at about the same time, the mid-70s. That shot in ‘The Passenger’ we will return to shortly since the issues of silence and colour will need to be tracked till the end pt. his film carrer. The colour phase of which began with his rather elliptical comment while filming ‘Red Desert’: “If there is still an autobiographical element, it must be found in the colours.”

Image Courtesy: Flickr, Pinterest, Newsclick, Arte Magazine, Film Art Gallery, Kaput Already

Shankarlal Bhattacharya

Born on 15th August, 1947 in Kolkata, Sankarlal Bhattacharya is a gold medallist in English Literature. He received his training in journalism from Paris, immediately after which be forayed into the world of writing. He has worked as a journalist in the Anandabajar group and has over 130 books to his credit. Aside from short stories and novels, he has written biographies for Ravishankar called "Raag Anurag", for Bilayat Khan called "Komal Gandhar" and has also been the co-writer for Hemanta Mukhopadhyay's memoir "Amar Gaan-er Sorolipi". He has translated widely from Shakti Chattopadhyay's poems to Satyajit Ray's screenplays