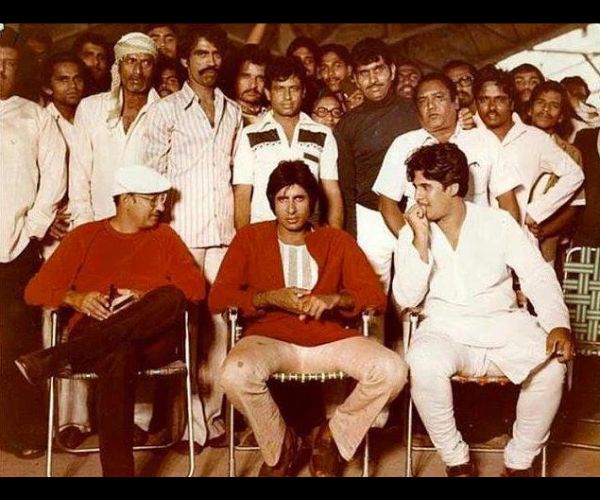

Manmohan Desai was born on 26 February 1937 in a family of film producers. His father Kikubhai Desai owned Paramount Studios and grandmother ran a movie theatre in Pune. Desai, the pioneer of ‘masala movies’ was the uncrowned King of Bollywood in the late seventies. In 1977, three of his fast-paced extravaganzas were released over a span of 52 days and all of them became runaway successes. One of them, Amar, Akbar, Antony – a melodramatic tale of secularism based on the camaraderie between three young men, a Hindu, a Muslim and a Christian – was one of the first set of commercial Indian films to be broadcast by BBC television at prime time. With its way-out fantasies, saucy song and dance routines and convoluted plot, Amar, Akbar, Anthony broke all Indian box-office records. It also established the career of Amitabh Bachchan, who subsequently became a legend in Indian cinema.

Anhonee ko honee karna hamara kaam hai.’ (It is our job to make the impossible possible.) The sentence leading into the title song of the blockbuster film Amar Akbar Anthony sums up the magic of Manmohan Desai, the master entertainer whose desire to please his audience made his name synonymous to success during much of his career in popular Hindi cinema from 1960 to 1988.

Connie Haham, who has written Enchantment of the Mind – Manmohan Desai’s Films (Roli Books, 2005) analyses in great detail, some of his cinematic signatures such as speed, fun, adventure and delight, alongside a devotion to motherhood and a stance in favour of inter-religious harmony. His cinema is fondly remembered for its many catchy tunes and the characters brought to life by leading stars, from Raj Kapoor to Amitabh Bachchan. Lending extra magic to Connie Haham’s book is the part where Manmohan Desai narrates his artistic style and approach to cinema to stress not only the positive sides of life but also to depict the struggles life mandatorily imposes on every man and woman.

His first film was Chhalia (1960) starring the very unconventional pair of Nutan and Raj Kapoor. Manmohan was then barely in his twenties. The film was filled with very entertaining songs wired in with a romantic love story with Nutan in an out-of-the-box role. He went his own way and did what he really believed without paying attention to the ever-changing trends and contents in cinema with time and audience preference. This, he continued till his last directorial venture Gangaa Jamunaa Saraswathi (1988) after which he handed over the directorial reins to son Ketan.

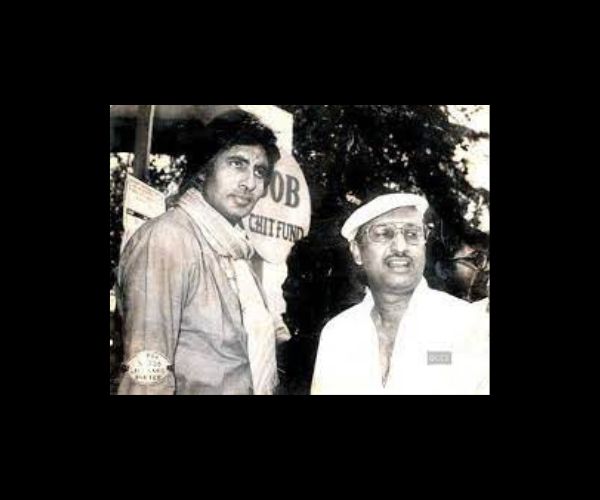

One will forever remember Superstar Amitabh Bachchan in Coolie (1983), pacing through one of the many stylised fight sequences he shot for many Bollywood filmmakers. The locales rarely mattered– it could be a seedy tavern, a vast desert, a slum alley, an underground car park or a revolving restaurant atop a Bombay skyscraper. However, in Coolie, the setting does matter– this is Bachchan’s and Desai’s most political film, and the fight sequence is part of the coolies’ revolt against capitalist and political corruption. It is choreographed as meticulously as a ballet or an Indian classical dance program. Bachchan is pinned against a column and an overturning poster, about to be punched by his antagonist when the screen suddenly freezes, and an astonishing caption in three languages covers the screen.

Coolie, released on 2 December 1983 turned out to be the most successful film at the Indian box office that year, going on to sell over 70 million tickets in twelve months. While shooting the scene Amitabh had miscalculated a movement, and the ‘fake’ punch hit him for real and he staggered onto the corner of a table, rupturing his spleen. The injury was near-fatal. All of these movements are captured in freeze-frame for the audience to remind them of what had exactly happened. Considering that the audience had not seen this happening during the shooting in real life, and also, the tremendous box office popularity of Amitabh Bachchan at that time, people thronged to the theatres to witness what they had not been privy to. This was decades before ‘behind the scene’ shots became popular promotional tools in cinema. Perhaps, Manmohan Desai wished to establish, as an afterthought of course, the interaction between illusion and reality central to the cinema of Manmohan Desai.

Coolie, released on 2 December 1983 turned out to be the most successful film at the Indian box office that year, going on to sell over 70 million tickets in twelve months. While shooting the scene Amitabh had miscalculated a movement, and the ‘fake’ punch hit him for real and he staggered onto the corner of a table, rupturing his spleen. The injury was near-fatal. All of these movements are captured in freeze-frame for the audience to remind them of what had exactly happened.

Of the 20 films he made between 1957 and 1988, 13 were among the top ten grossers of their year – the highest success ratio in the history of Bombay Cinema, and three were the most successful of the year: Amar Akbar Anthony (AAA, 1977), Suhaag (1979) and Coolie. 1977 was Desai’s triple triumph. With the regular release schedule suspended for two years because of the Emergency, four of his films were released in this year, becoming the first, second, fourth and fifth highest grossing films (Amar Akbar Anthony, Dharam Veer, Parvarish, and Chacha Bhatija respectively). AAA and Dharam Veer were among the ten best grossing films of the 1970s and Coolie, Naseeb (1981), and Mard (1985) of the 1980s. This stands testimony to the contemporary reach of Desai’s work, which extended to re-releases in the ’90s when even comparative flops like Desh Premee (1982) and Gangaa Jamunaa Saraswathi (1988) found large new audiences. Desai’s blockbuster formula of all-star casts and spectacle- or set-piece-structured narratives became and continues to be the dominant mode in Bollywood.

In his brilliant foreword to Hanan’s book, Amitabh Bachchan writes: “The story ideas of Amar Akbar Anthony and Coolie were inspired by real life. If they seemed like fantasies, it was because his USP was to make the tough reality palatable, underscored by optimism. His valorous protagonists did not die in his films; they lived even after they had been riddled with bullets. The most obvious example of this was the recovery of the eponymous Coolie, attacked by gunfire at the Haji Ali dargah. Miraculously, in real life too, I survived a serious physical injury on the sets of the same film. His concern and prayers were always with me, as they were indeed with all the actors and technical crew whom he treated as an extended family.” He goes on to add: “Manji, as he was called by those who loved and admired him, would perhaps balk at any cerebral analysis or research about his films. Without knowing it—like all great masters—effortlessly he had posited significant sub-texts into his hyper- fantasies, which, to the superficial eye, seemed like fleeting, will-o’-the-wisp entertainers.”

He did lead a very successful career and went on to create his own school, his own genre of filmmaking targeted mainly at entertainment with lots of music, dance, action scenes and social messages, true.

But the tragic reality of his life was quite unlike his scripts. He met with an unexpected death at the age of 57 when he fell off the balcony of his apartment. Rumour goes that he had committed suicide. His wife, the beautiful Jeevanprabha, had also committed suicide and her death had left him quite disturbed for several years. Gradually, his friends tried to fix up a match with the ageing actress Nanda who was single and had never married. But all hopes of seeing them married was nipped in the bud with Manmohan Desai’s untimely death. Some say it was suicide but it was never proven to be true. It remains a mystery till today.

Connie marvelously sums up Desai’s contribution in Indian cinema. And we will borrow her words to end this birthday tribute– “Needless to say, Manji has been frequently imitated but never quite equalled. Not by a long shot. Because part of the distinctive drive and brio of his work came from his instinctive belief that films

are a temporal as well as a spatial medium. He loved flamboyant colour, costume, and décor, but he never allowed these elements to freeze into static compositions. A genius of changing patterns and complex movements, he filled his pictures with swooping crane shots, voluptuous displays of story telling, dance-music-action,

superbly colloquial dialogue and spontaneously orchestrated background detailing.”

Image courtesy: Twitter

Shoma A. Chatterji is a freelance journalist, film scholar and author based in Kolkata. She has won the National Award twice, in 1991 and 2000. She has authored 26 published titles of which 14 are on different areas of Indian cinema. She holds two Masters Degrees and a Ph.D. in History (Indian Cinema). She has also won a few Lifetime Achievement Awards from different organizations over time.