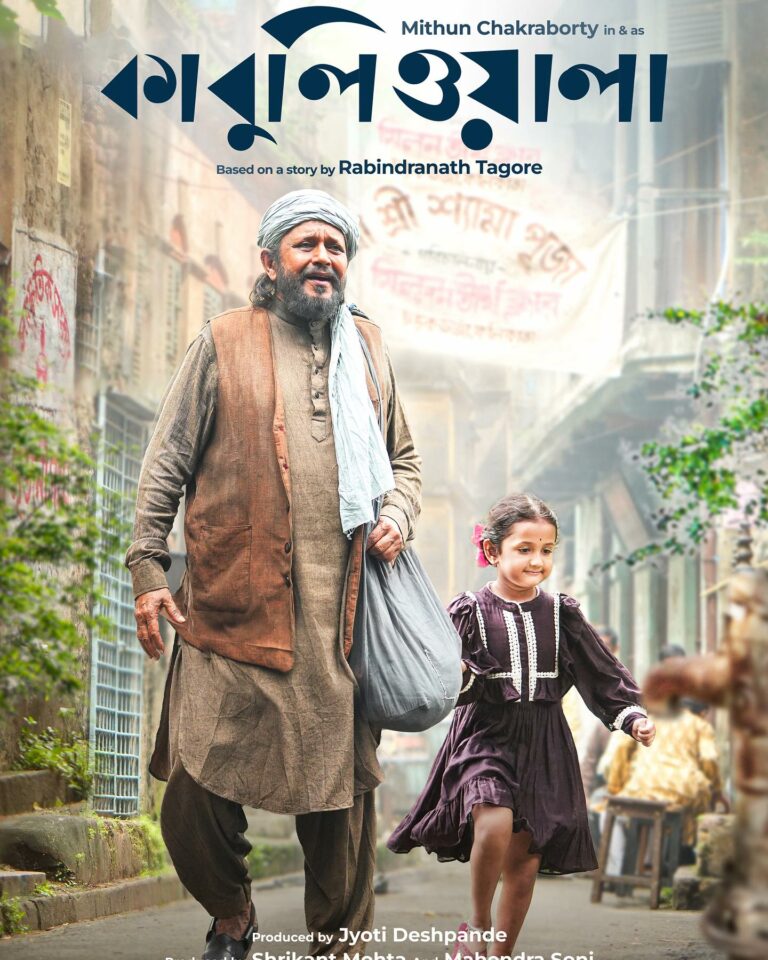

Suman Ghosh has directed 15 films, both short and feature films and documentaries. He also teaches Economics at the Florida North Atlantic University in the US. He takes sabbaticals to make films, mainly in Kolkata. His recent film Kabuliwalla, adapted from Rabindranath Tagore’s famous short story, has received positive reviews. It has also been a reasonably commercial success. But why Kabuliwala, which has already made decades back by Tapan Sinha with great success and then by Hemen Gupta in Hindi under the Bimal Roy banner? He explains in a one-to-one interview with this author.

Why Kabuliwala of all Tagore stories?

I thought of making Kabuliwala for my two daughters Maya and Leela. It felt necessary and my fatherly instinct urged me to make a film for them. I had this idea several years back when they were around five and six. It had to do a lot with the love and friendship seeded in the relationship between two individuals — a man from Afghanistan and a five-year-old Bengali middle-class girl in Calcutta — from two different worlds which I felt would ideally fit as a lesson in smoothening away the divisive feelings the world is reeling under right now. Rehmat Ali is a Muslim from Afghanistan and Mini belongs to a middle-class, urban, Bengali, Hindu family. But they bond wonderfully.

What made you cast Mithun Chakraborty in the title role?

Whenever I thought of making Kabuliwala, I thought of none other than Mithun Chakraborty. I have worked with him in Nobel Chor and I have a wonderful working relationship with him. I wanted someone who could speak Hindi very well because the character is not a Bengali and yet, would also need to speak in Bangla heavily accented with Hindi. So, I needed an actor who would be fluent in both languages. Besides, who else could I think of other than Mithun-da, tell me? (Laughs)

How did you nail down the lovely little girl you cast as Mini?

Her name is Anumegha KahaIi. I had auditioned many small girls for the role of Mini. I had not finalized her but my mother told me that she had watched her perform in a television serial and she was good. I think that clinched it and she was in.

What kind of prepping did you do with your main actors – Mithun, Anumegha, Abir and Sohini?

With Mithun-da, it was a long-drawn process. He had his own interpretation of the character. He said he had a friend in Afghanistan in Bombay when he was struggling and remembered very clearly how the latter talked, the throw of his accent and the intonation of how an Afghani speaks, and he used that. Then, we would sit down together and discuss every scene. We worked for six months to fine-tune the character. He would enact every scene for me and ask for my consent. If I did not agree, he would correct it. In this way, he gave flesh, blood and life to a new Kabuliwala. He also detailed how his clothes should be worn, how his body language, his gait and his manner of speaking would change over the 15-year span of the story. He amazed me with the depth and thought he gave to the character.

As for Anumegha, the main thing was to make her feel comfortable. The best way to achieve that would be not to make her ‘act’ but to have her behave naturally. I told her mother not to let her memorise her lines and to come to the sets with a blank page. The secret was to make her feel excited to come on the sets and not to feel conscious of the fact that she needed to ‘act’. We became friends. This was the secret that brought out the best in the five-year-old girl.

As for Abir and Sohini, who play Mini’s parents, I would have preferred a series of workshops, but this being a Bengali film, we had to work within budget and time constraints. Both were busy with other assignments. So, I read out the script to them and asked them to comment on how they ‘saw’ their characters. I would take down their comments and if I was okay with their suggestions, I would incorporate these into the script.

How long did it take to complete the film from conception to the censor board?

It took exactly one year for the film to complete from conception to the censor board. The first sitting I had with Mithun-da happened on 22 December, 2022. I already had the script in my head but I did not begin writing before Mithun-da said ‘yes’ which he did on 22 December. We began shooting in July 2023. The film had its theatrical release on 22 December, 2023.

What brief did you give to your music director?

There are two aspects to the music in any film. As a minimalist myself, so far as music goes, I try to be as subtle as possible, but the audience in Bangla films is used to loud music and songs. So, in this film, I asked my music director to go a bit overboard. We continued to work back and forth with the songs which needed to be less subtle with some restraint from my end. Anirban and Sujato did the lyrics and the music was by Indradeep Dasgupt. It worked out well in the end. This went on for three to four months till we arrived at the final results.

Which are the locations you shot the film in?

The time setting of my film is 1965. The city has changed dramatically over the years. Besides, in Bengali cinema, we need to work within tight budgets. So building an entire set for a period film is almost impossible. I must give the entire credit to my art director Tamnoy Chakraborty, who created the entire neighbourhood in New Theatres Studio One (where Mini lives, and the streets along which Rehmat sells his wares). Such neighbourhoods do not exist in the city anymore. So we did some shooting in Kumartuli, the potters’ colony, and at some areas of Bhawanipur which have not changed much. I am much indebted to Tanmoy for recreating them in an impeccable manner.

Directing Mithun on the one hand and the little Mini on the other was a very demanding proposal. Then the middle-ones — Abir and Sohini. How did you negotiate your directorial ways through this maze?

Actually, I did not need to ‘negotiate’ anything. Everything just fell into place organically because we had prepared in advance. I had worked on each and every character individually. They jelled together very well on the sets. I had told the little girl’s mother not to tell her anything about Mithun the star. She once commented that Mithun cannot dance which was really funny as Mithun-da is known to be an excellent dancer. This is because the film has a scene where she is teaching Rehmat Ali to dance and he makes a hash of it. But she was unaware of that and things worked extremely well.

What was your shot-taking ratio?

Roughly, it was three to one but in some cases, because of the little girl, we had to take her more. But she was so good, that in some scenes, we would ‘okay’ her after a single take.

Do you allow your actors to improvise on the sets?

This depends entirely on the kind of film I am directing and on the actors. Improvisations were done before we went on the sets. For example, last year I made Scavenger of Dreams in which all the dialogues were improvised. The film was screened at the Busan International Film last year. Both Shardul Bharadwaj and Sudipta Chakraborty spoke the dialogue they had created right during the shoot. For Kabuliwala, I had the entire script written down and nothing was improvised, except in the last scene when Mithun-da cries “kabuliwala” for the last time, which he had improvised. He always keeps room to improvise directly on the sets and he did not make any exceptions here too.

How do you describe your evolution as a director of significance and perhaps the only NRI who is also an economist?

(Smiles). I do not make distinctions between my being an economist and a filmmaker. I truly enjoy both. As a filmmaker, I am trying to work out a balance between the big films that are targeted at a mainstream audience, such as Kadambari, Bosu Poribar, Peace Haven, and Kabuliwala and the other films catering more to the ‘art films’ market like Searching for Happiness, Scavenger of Dreams, and the documentary films Shyamal Uncle Turns on the Lights.

All Images: The author, Facebook, Google, YouTube

Shoma A. Chatterji is a freelance journalist, film scholar and author based in Kolkata. She has won the National Award twice, in 1991 and 2000. She has authored 26 published titles of which 14 are on different areas of Indian cinema. She holds two Masters Degrees and a Ph.D. in History (Indian Cinema). She has also won a few Lifetime Achievement Awards from different organizations over time.