Uma Dasgupta is a renowned scholar and biographer of Rabindranath Tagore. In this essay she discusses at length the social and economic reforms undertaken and implemented by the Tagore family in the tribal villages around Santiniketan. Originally written as a paper to be read out at a seminar in the University of Illinois, this essay will be published in four parts on Space.ink.

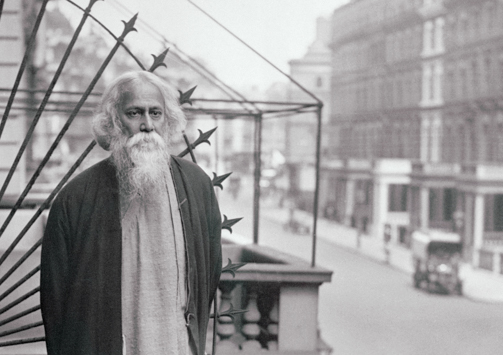

Though Tagore identified himself as a poet throughout his life, he also claimed that the poet’s or the artist’s work embraces religion. Religion was important to him. But this was no institutional religion nor any casual idealism which some of his own utterances could lead us to conclude. It was much more than that. His religion was his sense of responsibility to God and to man. It was an overwhelming feeling of God’s presence in man and nature. About it he wrote,

To me religion is too concrete a thing, though I have no right to speak about it. But if ever I have come to realise God, or if the vision of God has ever been granted to me, I must have received the vision through this world, through men, through trees and birds and beasts, the dust and the soil – I feel his touch in the sky, in the air, in water, everywhere I feel it. There are times when the whole world speaks to me.

Essentially, my religion is a poet’s religion … My religious life and my poetical life have followed the same mysterious line of growth. Somehow they are wedded to each other, and though their betrothal had a long period of ceremony, it was kept secret from me. Then suddenly a day came when their union was revealed to me.

At that time I was living in a village. The day brought all the drifting trivialities of the commonplace. I finished my morning’s work, and before going to take my bath I stood for a moment at my window overlooking a market place on the bank of a dry river bed. Suddenly I became conscious of a stirring within me. My world of experience seemed to have become lighted, and facts that were detached and dim found a great unity of meaning. The feeling that I had was like what a man, groping through a fog without knowing his destination, might feel when he suddenly discovers that he stands before his own house.

The idea of the humanity of our god, or alternatively the idea of the innate divinity of man, was central to Tagore’s religious experiences and to his poetry. It brought him the conviction that truth is found through man, that we can never go beyond man and living experience in whatever we know and feel. All those early experiences were developed in his Hibbert Lectures to Oxford University in 1930 and published in 1931 entitled The Religion of Man. The theme he expounded there was how the infinite became defined in humanity by seeking divine love and co-operation. Through this sensuous experience of reality he felt he had found his own religion at last, and it was the religion of man. He included his conversation with Albert Einstein in 1926 at the end of the book to elucidate his realisation. Einstein’s question was: ‘Truth, then, or Beauty, is not independent of Man?’ Tagore’s answer was,

Truth is realised through man … We individuals approach it through our own mistakes and blunders, through our accumulated experience, through our illumined consciousness…

Tagore’s school in Santiniketan was thus founded on the conviction that man could become truly human by responding creatively and sympathetically to his environment. Rathi, his son, was educated in this school before he went to Illinois. Before Rathi came to Santiniketan he was raised for some years in the family’s rural estates. And what an education that was! Among their regular visitors was the scientist Jagadish Chandra Bose who was at the time making experiments to compare the reactions on the Living and Non-living to different kinds of stimuli. About Bose’s exchanges with his father Rathi writes in his memoirs,

The attachment of the scientist and the poet was much more than just friendship. They would constantly exchange ideas. One would talk of the next story to be written and the other of the remarkable results obtained from the experiments carried on in his laboratory. They would not only appreciate each other’s criticisms but derive inspiration from their discussions.

To that Rathi added,

I would greatly miss him when he went away and secretly I would take a vow to become a scientist like him when I grew up.

Another regular visitor to the Tagore estates was the historian Akshoy Kumar Maitra whose hobby was cultivating silk worms. His commitment to this hobby was such that on Sundays he would discard all clothes and lie wrapped in newspapers among the caterpillars allowing them to crawl all over him. What could be more educational for young Rathi than to be a witness to all these unusual happenings? In spite of his mother’s misgivings Rathi also accompanied his father when his Rabindranath went on tours to look after the estates. He was then about a boy of seven sharing many an adventure and experience.

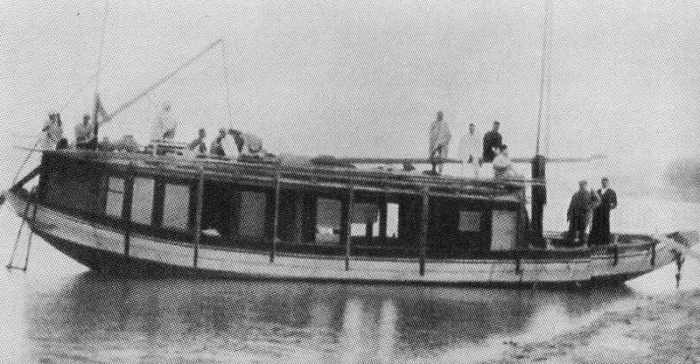

Their estates were extensive and in looking after them Tagore constantly toured through many districts of rural Eastern Bengal as far as Orissa. He did all this travelling in his favourite house-boat called the ‘Padma-Boat’ winding through small rivers that took him into the heart of the province so that he could observe the life of the people. Those small rivers were tributaries of the mighty river Padma, another name for the Ganges. Reared so closely to his father’s activities it is no surprise that Rathi also felt the pangs of the Swadeshi Movement for constructive nationalism.

Another regular visitor to the Tagore estates was the historian Akshoy Kumar Maitra whose hobby was cultivating silk worms. His commitment to this hobby was such that on Sundays he would discard all clothes and lie wrapped in newspapers among the caterpillars allowing them to crawl all over him.

This movement was active just before he came West to Illinois. Rathi wrote,

Another midsummer madness which took hold of me during the period between my Entrance Examination and departure for the USA was the fervour of an aggressive kind of patriotism. I was drawn into the whirlpool of politics that was agitating the country. The Swadeshi Movement in Bengal started at the very beginning of this century and reached its acme during the years 1905 and 1906. To us, nurtured from childhood in an atmosphere of all that nationalism truly denoted, it did not come as a surprise… In 1905 while I was spending a holiday at Giridih with Santosh Majumdar I was drawn into the thick of the movement.

In other words, these are illustrations that Rathi was finely tuned to his family’s traditions and the times in which he grew up. On his return with his degree from Urbana at the end of 1909 Rathi first went to live in Shelaidaha, headquarters of the family’s agricultural estates, where everything was kept ready for him. He was going to be the manager of those estates from now. His father personally took him round to acquaint him with his tenants and teach him the basics of management. After many years both of them were back in that houseboat touring the estates. In his memoirs Rathi wrote,

As we drifted along through the network of rivers so familiar to both of us, every evening we sat out on the deck and talked on all sorts of subjects. I had never talked so freely with Father before this, and I had to make considerable effort to break the ice. I think Father must have been hugely amused to hear me prattle and glibly repeat copybook maxims on agronomy, genetics, evolution and such subjects as were still fresh in my mind. Most of the time he would listen patiently but when he did talk he told me about the social conditions of our rural folk, the problems of their life and his own experience in dealing with them. Rarely did he talk on literature, probably thinking that my training in the sciences barred me from appreciating the arts.

That is how Rathi settled down to the life of a skilled gentleman farmer and continued to apply his knowledge usefully in an experimental farm where seeds of maize, clover and alfalfa were imported from America, as were several new equipment suited to Indian conditions such as discs and harrows. There was also a laboratory for soil testing. We have it from Rathi’s memoir that an American visitor had remarked that this farm in Shelaidaha was a “genuinely successful American farm”. From some of his letters of that period it seems that Rathi was feeling very committed to his new responsibility. He wrote to Mrs.Seymour, for example, on 21 February 1912, to explain why he was not willing to take a trip abroad at that time:

There are too many things that are demanding my attention – and I cannot, by any means, make myself free from them just now. You will realise this better when you hear how differently employed I am now, from the school-boy you used to know. The management of two large estates – each measuring about 60,000 acres – the looking after of some mining property, conducting of two small farms, agricultural investigation in connection with a laboratory for soil analysis, for all this I have to find time, though Nagen helps me a lot in some of these.

In an earlier letter he was talking about Shelaidaha becoming their permanent home, Rathi’s and his wife Protima’s. In it he wrote,

I have just come here for a few days on business. The house here, which will be our future home, needs repairs and alterations and is not yet quite ready – so that it will be a month or two before we move in here permanently.

But they could not stay in the estates for any length of time. In fact, if we examine the years after Rathi’s return from Urbana we find that between 1910 and 1912 he moved from Shelaidaha to Calcutta to Santiniketan to London to Illinois. We have just quoted from that letter where Rathi wrote how he could not take a trip abroad because he had so much work in the estates. But the situation changed when his father fell unwell and the doctors advised Tagore a long sea voyage.

Father must then have sought son’s help in taking that voyage and Rathi’s first loyalty was always, always, to his father. He went with him of course but thought of a plan by which he could ‘induce’ (Rathi’s own word) his father to come to Illinois from London so that he could put this trip to use by pursuing a doctorate in agriculture. He planned to do some more work on breeding of plants and on Mendelism. In July 1912 he wrote to Mrs.Seymour from London,

We have decided that I should take a year’s work at the Illinois University, while Protima will be trying hard to learn English from a private tutor.

Arrangements were accordingly made for them to spend a year in Urbana from September 1912. That was changed to a later start in end-October. Finally, they ended up staying only for about six months at Urbana. They were on their way back to London in April 1913. As Rathi wrote,

Father grew restless. I knew the symptoms too well. He had finished his writing and he felt the natural urge to communicate what he considered India’s message to the West. Fortunately an opportunity presented itself to Father to address a larger public in the USA. The Federation of Religious Liberals were holding a Congress at Rochester and Father was invited to give an address. His lecture on Race Conflict was greatly appreciated…Invitations began to pour in now from different universities. I had to go to Chicago to make arrangements for a series of lectures at that University…After Chicago the call came from Harvard and from New York for a series of lectures. I realised that the time had come to strike our little camp at Urbana and to give up my post-graduate studies. Not that I regretted it much.

There were more such travels to come Rathi’s way for his father was an indefatigable traveller. Rathi and his wife accompanied him again on overseas tours in 1920, 1924, 1926 and 1930. And these were by no means all of Tagore’s travels – these were the ones on which Rathi also went. However, from Rathi’s Travel Diary of their 1920 and 1926 visits which were published in his memoirs titled On the Edges of Time, it is clear that he was no less keen to travel for he found that enriching and stimulating for his life.

But then it must also be said that he could not pursue the cause of scientific agriculture and rural reform with any consistency or systematic attention whether he was working at the family estates or later at Visva-Bharati.

A historian and Tagore biographer who is a former professor of The Indian Statistical Institute. Friendships of 'Largeness and Freedom', Andrews, Tagore and Gandhi: An Epistolary Account, 1912-1940, Rabindranath Tagore an Illustrated life, Santiniketan and Sriniketan are some of her celebrated works. She is a noted Tagore scholar and biographer.