I was fifteen years old when I first read Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. I was a different person then—and a very different reader. I remember telling my friend that reading the book felt like being drawn into a dream. And yet, there was something primal about the way it extended beyond the comfort of casual reading. It was an experience in itself—a tapestry of words that felt like incantations, revealing a world that had always existed in some elusive fashion.

As I read the novel now, I am struck by how García Márquez politicizes this very ephemera, challenging the White Man’s systematic dismissal of the history of the colonized. For within the mists that surround Macondo and its memories of ice and war and ruin, García Márquez shapes into a keeper of time, a weaver of hope, a revolutionary waging a war against the forgetfulness that plagues our time on earth. one hundred years of solitude

I have realised over the years that when I talk of the book, I talk of the many images I have formed of it: of Remedios in flight and Mauricio Babilonia’s yellow butterflies, of Rebecca eating dirt, Úrsula’s aging hands, and Melquíades’ great return. I think of it as though it were a memory slowly fading from my mind; I remember solitude as though I have borne it beside Aureliano Babilonia sifting through his parchments, waiting to be condemned. one hundred years of solitude

Macondo, the town of miracle and tragedy, of rain that lasts for years and love that whispers beyond death and damnation, has long been a sanctuary of my own design, a space that has existed at the intersection of García Márquez’s threadwork and the colours of my own imagination. When I heard, therefore, that it was to be adapted into a show, I was quite cynical about how it would turn out.

This is a homage to Garcia Marquez’ radical act of historicising the magical, of politicising the personal, reinstating in a world of short-term algorithmic memory, that stories are born from people and time.

My opinion of book-to-screen adaptations stands on murky ground. I haven’t quite surmised whether I’d argue in favour of fidelity or creative freedom, but I must admit to feeling like a bit of a purist as I pressed play on Netflix’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. I was most intrigued by how it would capture the pining silences wielded so masterfully by Gabriel García Márquez—and struck, in turn, by the show’s use of sound and colour and riverine breeze when painting the emptiness that claws its way into the very heart of our story. one hundred years of solitude

Macondo unfurls on screen like a painting that moves in time, its misty haze pulsating with possibility. I was fascinated at first by the use of music—Camilo Sanabria and Juancho Valencia manage to strike a very strange chord in using the lament of harrowing strings and Andean flute to etch out the enormity of isolation. It is in the soundtrack that the book’s silences are best expressed—the churning of rain and wind against the entry of music and rhythm creates this staggering sense of nostalgia.

When coupled with the use of jagged cuts and sharp movements in the camerawork from one scene to the next, the viewer is led into a whirlpool of sorts—one that is not unlike the act of looking back upon one’s own childhood and scouring desperately for answers that never seem to arrive. one hundred years of solitude

The set design is breathtaking as it traces the evolution of Macondo from the home of possibility to a ghost town on the brink of ruin. The early scenes, where José Arcadio Buendía discovers ice and dreams of progress, are painted with golden light and wide, open spaces, physically calling upon hope in a town yet untouched by time. one hundred years of solitude

The river glistens like liquid silver, the trees hum with unseen voices, and the first houses, made of reeds and mud, seem to hum in the promise of an unrealised story. There is a sense of magic in the air, and Macondo feels like a dream come alive. As the series progresses, the weight of war, colonialism, and isolation seeps into the scenery. The town that once teemed with discovery begins to collapse under the burden of its own history. one hundred years of solitude

The once-vibrant hues of the landscape begin to dull; the houses, which had once held the promise of boundless imagination, grow darker, their walls thick with dust and silence. The blues take over, as the greys fester on. It is in its ability to translate the condemnation of this world into the very movements of its characters that the show truly emerges victorious. one hundred years of solitude

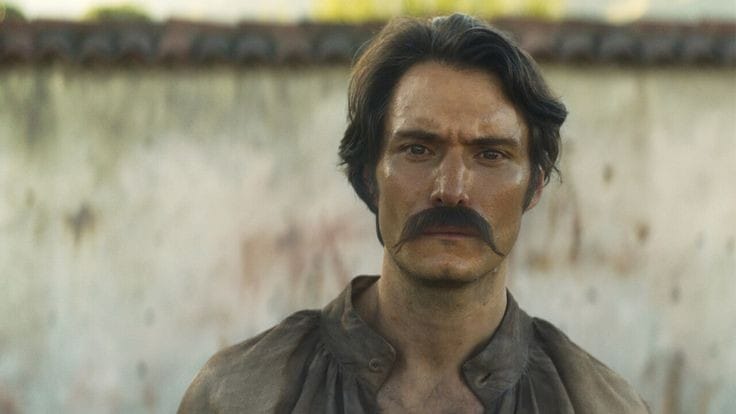

The show spends time in searching for history within the bodies of its characters—Aureliano Buendía does not need to speak because his eyes testify to the devastation he has witnessed over the course of his life. Úrsula, in particular, carries the quiet resilience and wisdom that seemed so tangible through the words in the novel.

There is a distinct weight in the way she moves through the set, ever-present but never overwhelming, an anchor to the rest of the Buendía family. Even in her smallest gestures—a steadying hand on a shoulder, a lingering gaze as she watches Macondo change before her eyes—she carries the triumphs and the tragedies of a woman who has lived through the birth and death of too many promises. one hundred years of solitude

Also Read: When The Word Is Made Flesh: A Review of Kannanari’s Chronicle of an Hour and a Half

The first season, spanning eight episodes (and about eight hours), traverses through the first seven chapters of the book- allowing some room for the word to be spun into moving frames. But I do still believe it impossible to truly adapt the weighted solitude of García Márquez’s prose into any secondary form- let alone visual imagery that must move forward at a given pace. one hundred years of solitude

And yet, what the adaptation achieves is a tribute—a recognition that Macondo, in all its beauty and tragedy, is a place that belongs to all who have ever wandered through its pages. It is in faithfully remembering these races condemned to a hundred years of solitude upon the earth, in casting Colombian faces to tell Colombian stories, in acknowledging lines from the novel as a guide from one sequence to the next, in keeping the landscape of the show unfalteringly honest, that Alex García López and Laura Mora are able to grieve the oblivion cast upon seven generations of the Buendia family- what could be more of a second opportunity on the earth than a hundred faces brought to life?

This is a homage to Garcia Marquez’ radical act of historicising the magical, of politicising the personal, reinstating in a world of short-term algorithmic memory, that stories are born from people and time.

I am grateful to the show for making me remember. I am glad that it has made me dream again. I do not want to measure the success of the television series against the enormity that is Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude.

I will remember, instead, the people it has brought me, I will remember the melody I have found. When I read the book again, I am sure this music will find me. And if I were to speak at length about the screen adaptation, I would pause at the eyes, at the dreary morning skies—on dying cries for revolution that echo far beyond the confines of episodic hours. One Hundred years of solitude

Image Courtesy: Author, Creative Commons

One Hundred Years of Solitude

Yashodhara Gupta(she/her) is pursuing her Master’s Degree from the Department of Comparative Literature at Jadavpur University. Her areas of interest include Diaspora and Postcolonial Theory, African-American Poetry, Feminist Literature, Studies of the Global South, and Film.