(Tom Stoppard)

Tom Stoppard who passed away on November 29 had an Indian connection. Born Tomáš Sträussler in Czechoslovakia, his family fled the Nazis to India, where he lived till he was about eight years old. His play Indian Ink (1995), a stage adaptation of his radio play In the Native State (1991), is his most direct engagement with the country. The play contrasts India during the 1930s British Raj with the modern India of the 1980s, exploring themes of colonialism, post-colonial cultural appropriation, memory, art, and identity. (Tom Stoppard)

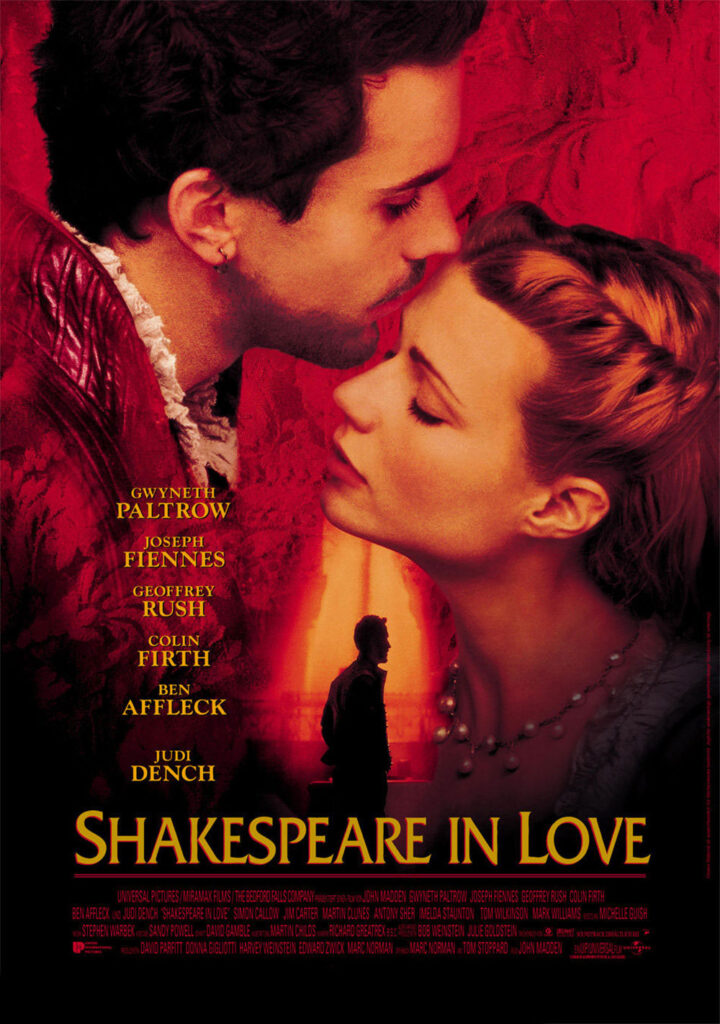

Otherwise, Stoppard is known for plays that include Rosencrantz and Guilderstern Are Dead (1966), Jumpers (1972), The Real Thing, (1982), Arcadia (1993), The Invention of Love (1997), The Coast of Utopia (2002), Rock n Roll (2006), and most recently, Leopoldstadt (2020). Among his screenplays are Brazil, Empire of the Sun (1987), Anna Karenina (2012) and Shakespeare in Love (1998)for which he received an Oscar along with Marc Norman.

Also Read: The Fine Arts of Criminology

Saikat Majumdar needs no introduction to those who follow Indian writing in English. Author of novels such The Firebird, The Scent of God, The Remains of the Body as well as several books of nonfiction and literary criticism, his role as a professor of English and Creative Writing at Ashoka University keeps his mind alert to the many genres of literature. Here I talk to him about Stoppard’s legacy to teaching playwriting and his own association with Bengali theatre through his mother who was an actress. (Tom Stoppard)

MM: Hello and welcome to Thespace,ink. I was looking to speak to someone who studied Tom Stoppard and perhaps also taught him to understand the importance of studying and teaching plays which are so much part of our literature syllabi, like poetry is. Can you give me your thoughts on Stoppard who may or may not have struck a chord with everyone, even say yourself. Pinter, Osborne, Williams, Miller (Arthur) whom we recall with much more passion. (Tom Stoppard)

SM: Those were the wonderful mid-century playwrights who brought together the European tradition of the theatre of the absurd, with more homegrown English traditions, such as the Angry Young Movement, famously illustrated by Jimmy Porter in Osborne’s Look Back in Anger. The existential strain was powerful in Stoppard, and I think he, along with the likes of Pinter, created powerful connections between literature and film, often writing memorable screenplays adapted by Hollywood.

“Conflict is crucial to any art form, but conflict embodied in exchange and dialogue is something that becomes the entropy of a play.”

MM: It is said that his (Stoppard) work is characterized by a unique fusion of high-brow philosophical inquiry and low-brow theatrical farce, creating a body of drama that is simultaneously demanding and profoundly entertaining. His central achievement lies in his ability to make abstract ideas—from quantum mechanics and entropy to post-structuralism and epistemology—palpable and funny on stage. (Tom Stoppard)

SM: There are many striking things about Stoppard’s work that also offer a sense of the literary zeitgeist. The way he rewrote Shakespeare, for instance, was very much part of a Post-modernist strain that sought to refashion canonical and classical texts, ranging from the Bible to Shakespeare to Victorian novels with new angles, often from deeply political ones that foregrounded the deadly midcentury political stalemate such as the Cold War. How this interacts with the absurdist instinct, connected to the bleak politics of the time, is something that makes him kindred to not only English-language playwrights such as Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter, but also European playwrights such as Eugene Ionseco. (Tom Stoppard)

“I’m very much a creature of reading and writing and the solitary exchange of these acts. I admire the performativity of certain genres, such as theatre, music, and even oral poetry, but the silence, lonely sociality of prose is what defines me.”

MM: Don’t you agree (and I can be wrong) that by taking on Shakespeare, his breakthrough play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, written in 1966, places two minor characters from Hamlet at the center of the action, his inversion of Shakespeare is actually a tribute to the great playwright? Sorry for that long sentence/ of a question. (Tom Stoppard)

SM: Absolutely, as I say above. But a Shakespeare written in the spirit of Stoppard’s own time. It’s also a testament to the timeless humanity of the Bard and his continued relevance to temporal and cultural contexts far beyond Elizabethan and Jacobean England. (Tom Stoppard)

MM: More than a novelist, don’t you think a playwright plays around with several characters like they were his puppets in action?

SM: A play is a fascinating genre as it links the literary with the performative. By literary here I mean the textual, particularly that connected with print literacy and private expression and consumption that the European enlightement and Modernity brought to the fore. Conflict is crucial to any art form, but conflict embodied in exchange and dialogue is something that becomes the entropy of a play. That is what is mesmerizing about a play, which can abandon other literary features like narrative or storytelling, as it happens with these existential and absurdist playwrights such as Stoppard, Beckett, Brecht and others in the early and mid-twentieth century.

MM: As one who is primarily a novelist, have you considered writing a play since you have been a close observer of the Bengali stage?

Also Read: Kafkaesque to Kalia

SM: I’m very much a creature of reading and writing and the solitary exchange of these acts. I admire the performativity of certain genres, such as theatre, music, and even oral poetry, but the silence, lonely sociality of prose is what defines me. But I think I have a kind of romantic envy of the performative, which has shaped some of my writing. The tension between the spectacle of performance and the quietness and loneliness of prose, I think, has animated some of my key novels. (Tom Stoppard)

MM: Your novel The Firebird looks into the world of the theatre space as occupied by women at a certain time, perhaps you could write a play about a novelist – there I have given you an idea. (as if you needed one!)

SM: Yes, The Firebird (also published as Play House) is the work of mine that is driven by the energy of the theatre. As you know, the key connections here are personal – my mother was an actress, primarily in the theatre but also sometimes in films and television, and her life in performance created some social and personal traumas in my life, including the breakup of my family. So theatre is a very powerful force in my life, and one associated with primal, visceral memories. But these are also dark memories. (Tom Stoppard)

Much of that came out in The Firebird, which tells the story of a young boy’s destructive relation with the art form of theatre through his mother’s life as a stage actress. It is largely fiction though inspired by many real-life memories.

“I haven’t really followed plays in Bangla seriously in the last couple of decades, but the few plays I’ve watched whenever I’ve returned to Calcutta haven’t really left a mark on me.”

MM: As a professor of creative writing, do you teach the different genres of writing literature separately – like poetry, drama, novels, short story because each genre has its own demands and expressions?

SM: I have taught a general introduction to creative writing where we work on multiple genres. And I also teach a course called Reading for Writers, where we read works of all genres from the perspective of working writers. My advanced courses focus on prose, as that is the genre in which I write – both fiction and non-fiction. I teach plays in my introductory courses and I talk about the importance of novelists reading plays and scripts as a way of writing dialogue. (Tom Stoppard)

MM: Coming to the Bengali stage, what we have been seeing since post IPTA is that adaptations are very popular. Very little of original work. Do you think we could do with more homegrown plays? Translations of Indian writing into English and vice versa?

SM: As a child, I remember catching what was perhaps the tail end of great Bangla theatre, both in the group theatre tradition with the likes of Kumar Roy in Bohurupee, Manoj Mitra in Sundaram, Utpal Dutt in PLT, and Meghnad Bandopadhyay in Sayak – as well in the very last remnants of the commercial of professional theatre of north Calcutta, with people like Subhendu, Sabitri, Soumitro, and Aparna Sen. (Tom Stoppard)

I haven’t really followed plays in Bangla seriously in the last couple of decades, but the few plays I’ve watched whenever I’ve returned to Calcutta haven’t really left a mark on me. Commercial theatre is long dead – I wrote this essay on this phenomenon in Caravan while I was researching on theatre for The Firebird – and group theatre has either become too commercial or too propagandist. But I really can’t evaluate it properly as I don’t know the scene in any wholeness. (Tom Stoppard) (Tom Stoppard)

(For those interested may look up the Caravan essay: The Ashes Of Pleasure.

Also Read: The Great Indian Proposal Letter

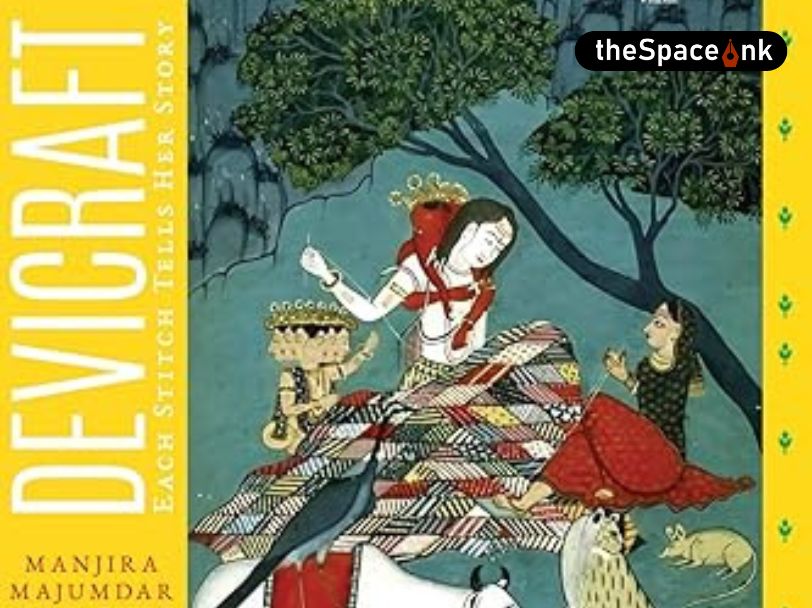

MM: Do you think mythology, drama, poetry in epic style make for an explosive combination but that people have no longer any time for?

SM: Mythology is always popular in India, in performance, novels, films, television and even video games. I enjoy mythology (and I have even written a college campus novel that re-imagines the Drona-Ekalavya story in today’s world), but what I would like to see more of is the story of the ordinary everyman and their quotidian loves and fears and hates and passions. The great mid-century playwrights with whom we opened this conversation elevated this to memorable and striking art.

Photo Courtesy: State Magazine. STIAS, Scroll.in, University of Cape Town, Local Samosa.

For a living, Manjira Majumdar has traversed the world of reporting, feature writing and editing. Today an independent journalist, she likes writing essays, fiction and translating from Bengali to English.