Column recap:

Iron Rules of History

Russian Lullaby

The Uses of Exile

Putin & Bengali Cold War

Imperialism in One Country?

Scratches on the Record

The Progressive Bookseller

The 18th Brumaire of Isaac Asimov

Identity and Vegetables

Joys of Parochial Self-effacement

How To Be A Person With A Voice

***

It was a long time ago: driving to a ballet performance in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in the back seat of a car driven by a white woman with the passenger seat in front occupied by a person I’d have called black in Britain, and would probably have referred to as Afro-American in Minneapolis or anywhere else that side of the pond (and I’d have simply assumed the ‘American’ part of it, because it’s rude to ask, innit?). But I wouldn’t have described either of them with that epithet – one of them was a friend, and the other was her friend (and former lover?) – I tend not to need to know about other people’s lives in any detail, nor their identification with gender, caste, class, or race categories. Except that this was exactly the issue: what colour we were. One of the women (guess which one?) turned back to me and said:

-I have to tell you, your hair offends me. It’s cultural appropriation.

-What?

– It’s cultural appropriation.

Her friend readily assented to this description of the cultural politics of what I had on my head.

Now, living in Berlin, I have heard that expression far too often, from people of colour anxious to reappropriate dreadlocks from the counterculture of white dropouts who wore them as a sign of separation of themselves from the boring (white?) mainstream of their origins. I found it quite sympathetic, although I noticed a slight guilt in their eyes when they looked at me – would I judge them? Would I be offended? I assured those who spoke to me that I was not, though I did tell them that there were indeed people who would be. To a white person, in Berlin, I as a person of more colour than they, had a right to my dreads, whereas they weren’t quite sure they had. It was up to me to reassure, or to attack, them. But then here, in the heartland of American PC, I was a little less certain: I was a guest, a foreigner, and my otherness stood out with every word I spoke.

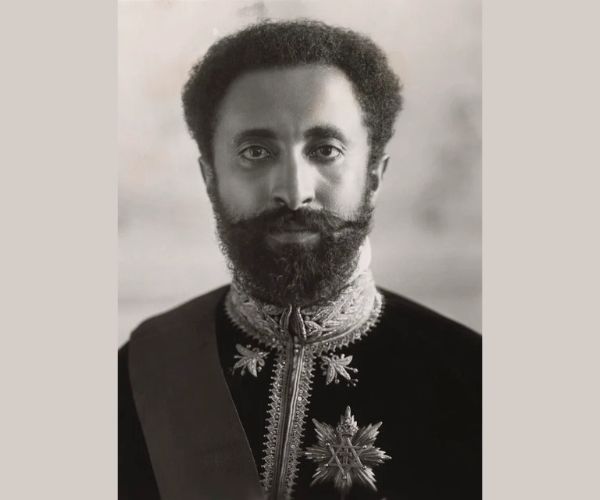

I patiently started my well-rehearsed narrative. ‘Dreadlocks’ were not, in fact, from North America, nor were they from the ‘original’ African cultures that former slaves were forced to forget in American captivity, and then painfully remembered in the 1960s and ‘70s: jata were brought to the West Indies by indentured labourers from India who replaced the slaves when ‘free’ labour was deemed to be more efficient than unfree slaves. Some of these indentured labourers were worshippers of the Hindu god Shiva, and it was Shiva’s depiction as a figure with matted hair that inspired their replication of the hair. In India, some sects of sadhus still have matted or dreaded hair. With time, in the syncretic environment of the Caribbean islands, they crossed over to black people from brown, and by the 1930s, were adopted by Rastafarians after the crowning of Haile Selassie as the Emperor of Ethiopia; but actually, the person most responsible for their spread was, unsurprisingly, one Bob Marley, deceased, formerly of Kingston, Jamaica.

Apologies were forthcoming: I was, apparently, by virtue of my Indian childhood and origins, allowed to have dreads. ‘But’, I said, ever the contrarian, ‘I’m Jewish’. (I’m not, of course; I’m an atheist, but for purposes of cultural assertion, I have a few identities I can draw upon, and I thought this was the right moment to use at least one of them disruptively.) Since we had now arrived at the performance venue, the subject was to have been politely dropped, and this last statement kept it alive, I hope, in their minds for long enough to complicate matters.

I was, I now discover, also wrong myself: hair in tangled locks dangling from heads has been known in many periods of history to many ‘cultures’, and since it’s relatively easy to acquire the beginnings of them simply by having tangly hair and not being too diligent with combs (which culture gave us combs? Are we allowed to appropriate them?), it is perfectly conceivable that this great cultural artefact was at least initially an inadvertent discovery or invention, rather like penicillin, Post-It notes, or the ice-cream cone. Some ancient Greek statues (from about the 7th century before the alleged birth of a would-be prophet from the Eastern Mediterranean who has been widely appropriated) have dreads, and these have not had the fate of the Elgin Marbles, of being polished with steel wool to remove those allegedly inauthentic characteristics, so we must believe that they were believed to be authentic. If we believe, as even the late Edward Said did, that Greeks were ‘Europeans’, or concede to the Greeks the origins of European ‘civilisation’, then Europeans can have dreadlocks without too many pangs of conscience. Whether various Sufi sects got them from the ancient Greeks, or from the Minoans, or the ancient Egyptians, is unclear; but the Cree probably didn’t get them from the Europeans in North America. Even the term doesn’t have a clear origin: we know it’s barbarians who made it up, because it doesn’t have a Greek etymology.

But is it really the point that we can bond across cultures on the basis of shared hairstyles? Or separate ourselves from one another on the same basis? Of course, we know how it works: we had it first, you took it from us – all culture is appropriation, and it’s only appropriate to remember this. But also – black trumps brown, ‘cos ‘we’ have caste; black people don’t oppress anyone. And all racism is internalised whiteness. That’s the logic, anyway. It follows that it’s always acceptable to be rude to white people, but it’s far more useful to let them be rude about themselves. It’s called critical whiteness, see? Meanwhile, don’t take our culture, but join us in celebrating the occasional black opera singer who breaks through. And the ballet dancers.

I wish, though, that the woke brigade would get out of my hair for a while. We’ve had far too many assaults on versions of history that someone doesn’t agree with for it to be merely stupid any more, and these assaults happen without evidence or rational thought, with affect and outrage for company: these are the new iron rules of history. We have also had far too many attempts to coordinate various kinds of assault on people at the wrong end of what currently passes as acceptable history. This is a legacy both of the Stalinist left and of lynch mobs – and it is a legacy shared among people who would be horrified to be associated with either.

I’m sure the photographer whose image of Che Guevara adorns t-shirts, coffee mugs and student hostel walls across the planet, might once in a while have had pangs of regret that he gets no royalties from the image (although he’s denied that he has on several occasions)[1]; but even if it is true that many Che image-users have very little idea of Che as a really-existing historical person, we don’t hear many appeals to disappropriate them of their Guevaras. Those who ran campaigns against a painter for her depiction of the body of the lynched Emmett Till while not having taken the elementary precaution of being black herself will have strategically forgotten that most of the world probably heard of Emmett Till, if they hadn’t read about it when the lynching happened in August 1955, via a song sung a few years later by a Jewish boy from Minnesota, the state in which the state of my hair created ripples at the wrong end of the Mississippi river.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of thespace.ink or its editorial team members.

Images courtesy: Pixabay

Notes:

- https://america.cgtn.com/2017/10/09/the-cuban-photographer-who-snapped-the-iconic-image-of-che-guevara

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of thespace.ink or its editorial team members.

Benjamin Zachariah works at the Einstein Forum in Potsdam, and with the project on the contemporary history of historiography at the University of Trier. He was trained in the discipline of history in the last decade of the previous century. After an uneventful beginning to a perfectly normal academic career, he began to take an interest in the importance of history outside the circle of professional historians, and the destruction of the profession by the profession. He is interested in the writing and teaching of history and the place of history in the public domain.

One Response

Informative , quirky and fun. Thanks Ben