Language operates in the biome for a very basic and specific reason – communication. It does not have any other objective. With time, in the human civilization, society manifested multiple objectives to enhance its association with communities on a geographical and anthropological level. In quantum physics, we study matter and energy through the constituents of atoms at the most fundamental level.

Similarly, to understand society, language becomes the primary constituent for common citizens as well as researchers. It became the axis around which communities started to operate. In many cases, it enhanced the culture of society as a whole.

In some cases, people began to take pride in their language and for which, strict borders were drawn around communities mainly on the basis of what and how they speak.

For example, the Brahmins of late 18th century accused the Mughals of corrupting the Devanagari Hindi with Hindustani language. It penetrated through various generations and now the ruling party’s decision of changing names of roads and railway stations since they subscribe to Hindustani language does not seem surprising. This kind of pride on a language is also responsible for oppression of another language which belongs to our own country.

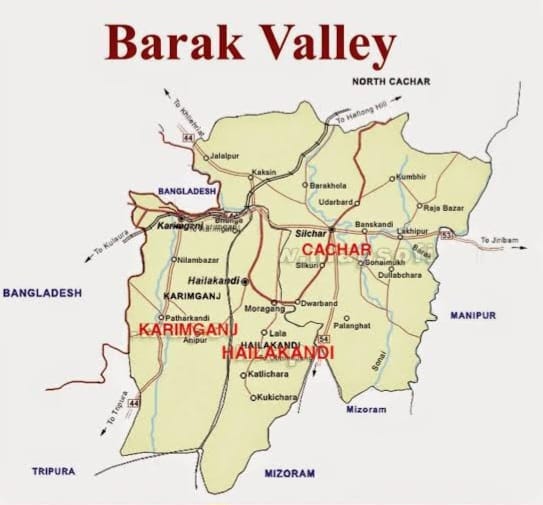

Our cultural dementia and ignorance have a ripple effect. It makes an entire nation isolate a particular region since its fight has been deliberately suppressed to enhance the delusion of peace. Therefore, on the eve of International Mother Language Day, it becomes necessary to remember the Bengali Language Movement (Bangla Bhasha Andolan) of Barak Valley, a valley located in the southern part of Assam.

The other parts of India, including Kolkata, the hub of Bengali speaking people, do not put any effort towards engaging their intellect in understanding a movement which happened after the Assam State Police shot down 11 protesters on 19th May 1961 at the Silchar railway station. The entire protest was against the decision of Assam government to make Assamese the official language of the state knowing the fact that an entire part of the same state is home to more than a million Bengali speaking citizens.

Similarly, in 1971 and 1986, when people from Barak Valley chose to protest when the state government became hellbent on making Assamese a part of school curriculum in place of Bengali, several protestors were put behind bars and tortured for the love of their language.

The violence that brewed in those times is a consequence of a strange and harmful pride that thrives inside the majority population of the state.

Although, history tells us that the province of Assam has always been an abode to people who arrived from many parts of the country/world, and those who ruled the province maintained its diverse attitude towards the human resource which helped in developing its economy, culture and literature. After the government implemented NRC/CAA all over India, its unconstitutional aggression made everyone come out on the street. But when the same law was implemented in Assam and its aggression parted people on the basis of language, no one chose to place this situation in the national media

A Look Back at the Two Dimensions of Assam’s History

The First Dimension: Violence, Unrest, Dissent in Brahmaputra and Barak Valley

In the year 1960, when the Congress Committee of Assam chose to declare Assamese as the official language of the state, the citizens of Barak Valley understood the politics behind it and confronted them with an official letter to keep Bengali as the official language of the valley. The state government declined the appeal and this enraged the people of Barak Valley and they organized a protest against the state authorities.

Despite the appeal and protest, the then Chief Minister of Assam, Bimala Prasad Chalia, made Assamese the official language of Assam. During this protest, a group of extremists attacked the Bengalis of Brahmaputra Valley which later forced them to either leave for West Bengal or to take shelter in the Barak Valley region.

According to history, Bengalis of East Bengal (Bangladesh) and West Bengal were invited by the British Raj in the province of Assam to work in tea gardens and coal mines to enrich the economy of Great Britain. The influx of Bengalis happened because the local Assamese citizens were unwilling to work in gardens and mines. For this, more than two lakh Bengalis were asked to settle down in the region. Some chose to settle in the villages of North Assam whereas a group of Bengalis chose to settle down in the Brahmaputra valley. With time, the British officials provided them jobs in clerical and administrative sectors of various institutions under their rule.

Also Read: Women’s Writing in Adaptation: New Perspectives, New Beginnings

The anger of the majority was towards a historical situation in which Bengalis had no role to play. They simply followed the instructions of the colonizers to maintain their livelihood. The politics of dividing Assam on the basis of language subscribes to the idea of manipulation which is followed by election victories.

The unrest of 1961, 1971, and 1986, if seen from an observer’s lens, made the politics vivid before the Bengalis. In 1960, when more than 25 villages were burnt in Kamrup, which led to death of nine Bengalis and injured more than a hundred Bengali speaking citizens, the rage against the linguistic politics made the Bhasha Andolan of 1961 a movement whose entire motive was to save not only the Bengalis, but also the language they speak.

Today when the figure of mass arrest is displayed in newspapers, the ignorance of the nation towards the subsequent protests of Assam solidifies the fact that these movements came out of fear and an urge of human beings to protect what they love. But, on the same hand, we witness the bombardment of policies by a community that should not feel vulnerable for its expansion of human resources comes out of insecurity and pride. This dimension of Assam’s history has been thrusted in a toxic pit of delusion.

The Second Dimension: Unrest with a Modern Tool in Hand

National Register for Citizens (NRC) and Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) was introduced all over the country and the authority asked the people of India to prove that they are the citizens of the country. In general, one who is an alien to the policies would take them as normal and legitimate, but one cannot look into its unconstitutional impact on the population of India.

At present, most sane individuals of the country are aware about its religious discrimination and how it injects toxicity through faith. What they do not know is NRC was first implemented in Assam to detect the immigrants who migrated to India either during the partition of 1947 or when West Pakistan created unrest in East Pakistan in the name of religion. History tells us that whenever NRC was implemented in Assam it always strikes a hammer on those who do not belong to the majority population of the state.

Thus, in 2019, the unrest in Barak and Brahmaputra valley mainly erupted when the policy targeted the Bengali Hindus and Muslims claiming that most of the Muslim immigrants came from East Pakistan during partition whereas the Bengalis migrated to Assam during the formation of Bangladesh. The ground report says that more than 10,000 people were sent to detention camps since they did not have proper documents to prove that they are Indians.

Little did the government care about the fact that these people arrived with nothing but their life in their hands and the memory of a land which was taken away from them.

Karimganj, Hailakandi and Silchar, three districts of Barak valley suffered most for the implementation of NRC in the state. History tells us that after the partition of Sylhet region through the Sylhet referendum, the British wanted the Sylhet region to stay in Bangladesh. Karimganj, being a major part of Sylhet, comprised more than a million Hindus.

After the partition, West Bengal sealed the roads that connects it to Karimganj, Hailakandi and Silchar. These roads were used for trading and travelling. The only passage that remained intact was the route that connects Sikkim and Assam, but the condition of these roads did not help both the regions in building a symbiotic relationship. Muslim-dominated East Pakistan wanted Karimganj to be a part of their province since the district had a massive Muslim population too.

The Congress Committee and its leaders did not want to accept Karimganj since it would spoil the homogeneity of the state. Finally, after a lot of round-table conferences, Karimganj was forcefully included as a district of Assam without the consent of its own people. During the NRC, the politicians wanted to bring discrimination in the minds of Bengalis of Barak Valley.

A cold war started to hover in the region wherein the act divided the Bengali community into two on the basis of religion. This allowed the politicians to build a substantial space to send their ideas to a region where Bengalis form the majority. After the pandemic, signboards of shops, offices and schools written in Bengali language were removed in the region and the owners were asked to alter the labels of the signboard into the language used in Brahmaputra valley.

Leaders like Pradip Dutta Roy, who stood against such activities were arrested by the state police. The cold war in the name of language is still very pertinent in the Barak Valley, and it is unfortunate that the cry of the people in chaos still has not reached the people who live in other parts of the country.

On the day of celebrating the mother tongue, the world needs to know about a region whose struggle has been chronologically slaughtered to display a picture in which peace is nothing but a lie.

The intellectuals of the rest of the country have never bothered to give us a platform on which we could place our dissent.

Neither have we received hope from those who are supposed to offer us something to look up to. Today the region does not have a proper airport, roads have more potholes than ever, and its educational sector fails to give anyone the freedom to speak their minds. Perhaps our vulnerability falls shorter than the many other vulnerabilities of this world. And two questions still remain unanswered: How far does one have to break to dream about healing? How can a community survive when its language is its biggest enemy?

Image Courtesy: Instagram, Bartalipi, Telegraph India

Kabir Deb is an author/poet based in Karimganj, Assam. He works for the Punjab National Bank and has completed his Masters in Life Sciences from Assam University and is presently pursuing his MCW from Oxford University, London. He is the recipient of Social Journalism Award, 2017; Reuel International Award for Best Upcoming Poet, 2019; and Nissim International Award, 2021 for Execellence in Literature for his book 'Irrfan: His Life, Philosophy, and Shades'. He runs a mental health library named 'The Pandora's Box to A Society called Happiness' in Barak Valley. He reviews books, many of which have been published in magazines like Outlook, Usawa Literary Review, The Financial Express, Cafe Dissensus, Sahitya Akademi, etc. He currently also works as the Interview Editor of the Usawa Literary Review.