Improvising on Neil Armstrong’s iconic statement, “That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind,” as he set foot on the moon on 20 July 1969 as the first man ever to set foot on the moon. One may boldly say about Chandrayan-3, ‘That’s India’s one more small step for humanity’s giant leap.’

When Vikram Lander of Chandrayaan-3 made a successful soft landing near the hitherto unexplored south pole region of the moon on 23 August 2023, it was definitely one more small but historic step for India in space research. With this step, India became the fourth country to land on the moon after the Soviet Union (now Russia), the United States of America and China. India’s successful maiden soft landing made it also the first country to land on the south pole of the moon.

Human knowledge is cumulative in character. We gain new knowledge based on the cumulative knowledge we have inherited. Therefore, what India achieved for itself with Chandrayaan-3 is achieved on account of what humanity has achieved over time; and what India achieves for itself is achieved for humanity. India’s discoveries by means of Chandrayan-3 will definitely be a significant step for global lunar research because it is to the south pole of the moon that the countries involved in space research want to send astronauts for future lunar exploration. Spending only 0.04% as a share of its GDP for space research, and hence having to work on a shoestring budget, the cost-effectiveness with which India made its Chandrayan missions happen is a significant encouraging factor for all global space research missions that do not enjoy large funding.

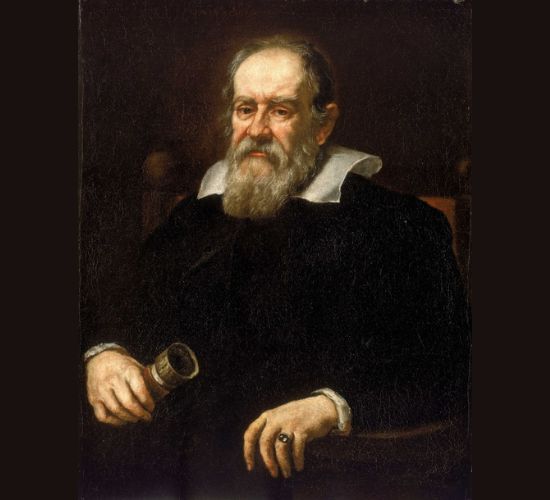

Serious lunar research in the world began with the invention of the telescope in 1609 when Galileo Galilei and other astronomers began making detailed observations of the surface of the moon with the telescope.

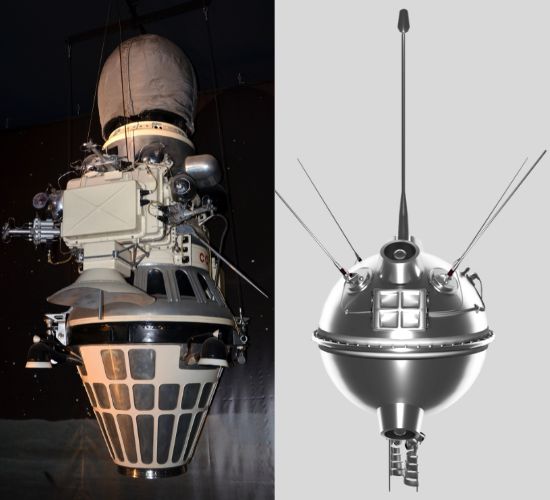

The second stage of the lunar research mission was the ‘flyby the moon’ mission inaugurated by the Soviet Union in 1959 whereby a spacecraft flies past the moon without entering its orbit or landing on its surface. Luna-1, the Soviet Union’s maiden flyby mission, captured images of the far side of the moon not visible from the earth. Soon, America launched Pioneer 4, its first flyby mission in the same year.

The third stage gave rise to the orbiter mission during which the spacecraft was placed in the orbit of the moon so that it could keep circling the moon studying it from close proximity for a long period of time. Once again it was the Soviet Union that launched the first successful orbiter mission, Luna-10, in 1966.

In the fourth stage, the lunar mission progressed into the impact mission, an enhanced version of the orbiter mission during which after the spacecraft enters the lunar orbit, one of its units gets itself detached and impacts, crash lands onto the surface of the moon. The impact mission is called so because of the intentional collision of the spacecraft with the moon. The crash landing or rather the hard landing unit of the spacecraft collects vital data from the moon and sends them to the control room on Earth. The other unit in the meantime keeps orbiting the moon collecting further vital data from the moon and sending them to the control room. The Soviet Union’s 1959 Luna-2 was the first impact mission. After the hard landing stage came the fifth, the soft landing stage which too was accomplished first by the Soviet Union in 1966 with its Luna-9 mission.

India’s Chandrayaan-1 was a combination of orbiter as well as impact missions while the partly unsuccessful Chandrayan-2 and the successful Chandrayan-3 were orbiter and soft landing missions.

The Sanskrit term, ‘Chandrayan,’ meaning ‘mooncraft’ is the name for India’s lunar mission. Announcing India’s entry into lunar exploration, on 22 October 2008, India launched its 386 crore Chandrayaan-1, its first lunar mission, from Satish Dhawan Space Centre at Sriharikota, Andhra Pradesh, the primary spaceport of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO). This was India’s first attempt to put an orbiter into a precise orbit around the moon as well as impact on the moon, and it was a spectacular success. This success placed India among the elite spacefaring nations of the world as well as announced India’s ability to set out on interplanetary missions and undertake scientific research in space that offers limitless possibilities.

The second stage of the lunar research mission was the ‘flyby the moon’ mission inaugurated by the Soviet Union in 1959 whereby a spacecraft flies past the moon without entering its orbit or landing on its surface. Luna-1, the Soviet Union’s maiden flyby mission, captured images of the far side of the moon not visible from the earth. Soon, America launched Pioneer 4, its first flyby mission in the same year.

As the spacecraft entered the lunar orbit at a distance of 100 km from the lunar surface, one of its units called the Moon Impact Probe (MIP) got itself separated from the other, namely, the orbiter unit. The MIP impacted or descended in a controlled manner onto the surface of the moon near its south pole. The MIP carried a set of payloads (scientific instruments) and successfully collected the desired data from the moon during its descent and impact. The orbiter unit kept circling the moon mapping the lunar surface and collecting data related to the composition of the surface of the moon, distribution of elements and so on. After functioning for 312 days and completing its mission successfully, on 29 August 2009, the orbiter unit lost connection with ISRO even though it was designed to be operational for two years.

Chandrayaan-1 mission was successful for multiple reasons. Its orbiter mission succeeded in taking detailed and high-resolution images of the lunar surface, thereby helping scientists create comprehensive maps of the topography, craters, and other aspects of the moon. It helped them to study the mineral compositions on the lunar surface which in turn helped them to study the geological history of the moon. It also confirmed the hitherto suspicion of the presence of water molecules on the surface of the moon, especially in the polar regions. Its MIP mission also provided vital insights into the gases around the moon. Corroboration of the presence of the inert gas, Helium-3, a potential fuel for nuclear fusion-based energy generation and which is rare on earth, is a significant discovery made through the MIP mission.

Riding on the success of Chandrayaan-1, on 22 July 2019, India launched a more complex lunar mission, the 978 crore Chandrayan-2 to undertake a comprehensive study of the mineral composition on the surface of the moon, measure its exosphere, investigate the distribution of water in polar regions, and study the lunar geological history.

A lunar orbiter, a lander called Vikram, and a rover called Pragyan were part of Chandrayaan-2. The orbiter was designed to map the lunar surface, examine the intensity of solar radiation, and study the wealth of chemical elements, minerals and water on the moon etc. Furthermore, it was also meant to serve as a communication hub for the lander and rover.

Vikram was designed to make a soft landing on the highland terrains on the south pole of the moon. It carried payloads meant to study the moon’s surface, environment, moon quakes etc. It housed Pragyan designed to be deployed onto the moon’s surface after a successful landing. Equipped with various payloads, Pragyan will also explore the moon’s surface and collect many important data.

The orbiter with the intended mission life of one year, entered lunar orbit successfully and began collecting and sending various data to the control room of ISRO. In fact, it continues to circle the moon and send valuable data even today. On the other hand, moving at a higher-than-expected velocity during the final stages of its descent, Vikram lost connection with ISRO’s control room and made a hard landing crashing both Vikram and Pragyan both of which were designed for a mission life of one lunar day, a duration of 29.5 earth days.

Learning valuable lessons from the mistakes of Chandrayaan-2, India launched its 615 Chandrayaan-3 on 14 July 2023. It comprised a propulsion module, a lander called Vikram and a rover called Pragyan. The propulsion module reached Vikram to a 100 km circular lunar orbit after which it separated itself from Vikram which then headed towards the moon for a soft landing.

Vikram was designed to make a soft landing on the highland terrains on the south pole of the moon. It carried payloads meant to study the moon’s surface, environment, moon quakes etc. It housed Pragyan designed to be deployed onto the moon’s surface after a successful landing. Equipped with various payloads, Pragyan will also explore the moon’s surface and collect many important data.

Orbiting the moon, the propulsion module would function like a relay satellite which would receive the signals coming from the seven payloads of Vikram, decode and send them to the control room of ISRO. Alongside the existing orbiter from Chandrayaan-2, the propulsion module of Chandrayaan-3 is expected to continue to orbit the moon for about six months (in fact it can go on for several years) performing all its assigned tasks after which it is expected to crash onto the lunar surface. One of the tasks assigned to the propulsion unit is to study the spectro-polarimetric signatures of Earth which involves the study of the way Earth’s atmosphere and surfaces interact with sunlight.

The high point of Chandrayaan-3 was the successful soft landing of its Vikram lander at 6.03 pm on 23 August 2023 on the south pole of the surface of the moon, an area scientists believe has deposits of rare precious elements and frozen water.

Space research and technology can significantly contribute to unprecedented economic growth as well as the all-around development of the world in several ways. Satellite science and technology, a branch of space science, for example, has changed life on Earth in significant ways enhancing the manner and quality of our communication, connectivity, navigation, remote sensing, climate and weather observation, ocean current monitoring, earth observation, forestation, disaster management, agriculture and food security and so on.

When ISRO was set up in the 1960s, Vikram Sarabhai, its founder and the father of India’s space programme, was convinced that India would undertake space research solely for the direct benefit of society and not for any competition with or domination of other nations.

Today India is looking forward to its two upcoming ambitious space missions – Gaganyaan and Aditya-L1. Gaganyaan would take a three-member crew to space for five to seven days to orbit the Earth at an altitude of 300-400 km from Earth. If successful India will be the fourth country to conduct a crewed space mission independently, after the United States, Russia, and China. Aditya L1, ISRO says, will place a spacecraft in a halo orbit around the Lagrange point 1 (L1) between the Sun-Earth system, which is about 1.5 million km from the Earth because as ISRO tells us, “A satellite placed in the halo orbit around the L1 point has the major advantage of continuously viewing the Sun without any occultation/eclipses.”

As far as space research is concerned, the sky is the limit. Let every small step that India takes in space research be a giant leap for humanity.

Images courtesy: ISRO & Wikipedia

Sacaria Joseph is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at St. Xavier’s College, Kolkata. Having pursued his undergraduate studies at St. Xavier’s College, he furthered his academic journey by obtaining a Master of Arts degree in English Literature from Pune University, a Master of Philosophy from Jadavpur University, Kolkata, and a PhD from Visva-Bharati University, West Bengal. In addition to his academic pursuits, he writes on a wide array of subjects encompassing literature, philosophy, religion, culture, cinema, politics, and the environment.