There’s a hope that’s waiting for you in the dark

You should know you’re beautiful just the way you are

And you don’t have to change a thing, the world could change its heart

No scars to your beautiful, we’re stars and we’re beautiful…

Once, a woman, who had just gotten through a mastectomy, was advised by a hospital nurse to wear a prosthetic breast otherwise, and this should be quoted, “it’s bad for the morale of the office”. The woman refused to take the suggestion, saying, “I cannot wear a prosthesis right now because it feels like a lie more than merely a costume”.

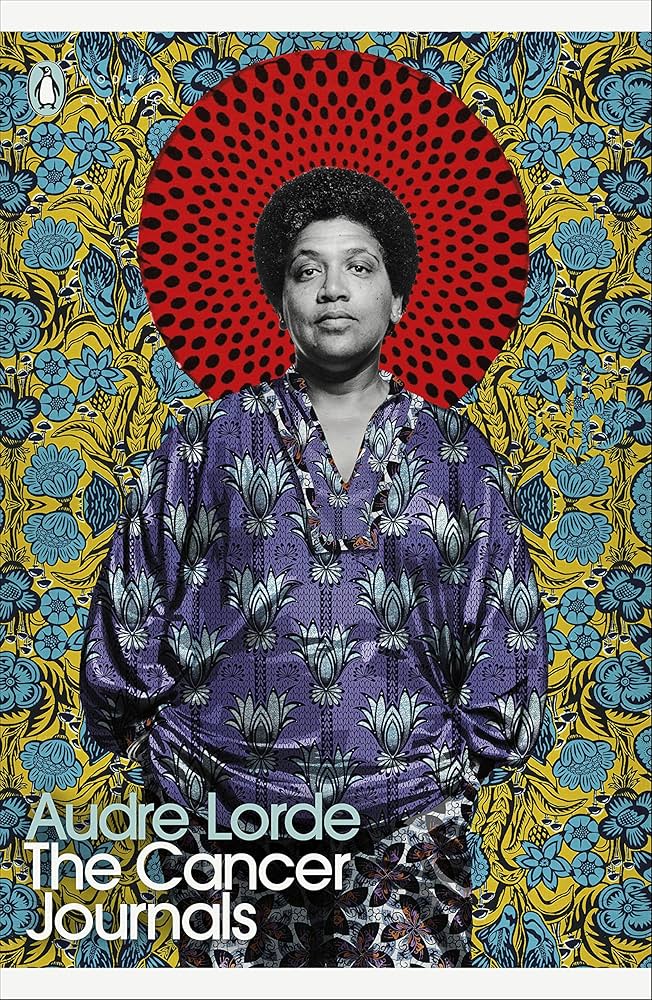

The woman was Audre Lorde, a Black visionary, writer, activist, and mother of two, who was raised in Harlem. Through her response she set an example of how it is important for a woman to embrace her own identity, her flaws, elements that define her and accept the above-mentioned lines, “you don’t have to change a thing the world would change its heart.”

Lorde entirely devoted her life and creative expertise to confront and combat the deluded ideas of racism, sexism, classism, and homophobia. She embarked on her poetic journey when she was only twelve years old. On Labor Day 1978, during a routine self-examination, Audre Lorde noticed a lump in her right breast, which eventually led to diagnosis of malignancy and the ensuing mastectomy.

She emphasises the importance of “voice” as a unique expression of identity.

Through writing, imagination, and language, authors convey their thoughts, emotions, and hidden truths using techniques like memoir, stream of consciousness, and symbolism.

Her works centre on female subjectivity, language, and literary identity, aiming to create a framework that reflects women’s experiences and redefines women’s literature.

The Cancer Journals depicts Lorde’s radical envisioning of self, body, and society through her own journey of illness, fear, pain, anger, and dawning clarity. The Cancer Journals follows the ideals of Virginia Woolf who believed that for a woman in order to raise her suppressed voice, she must “kill the aesthetic voice” as an “Angel” (Woolf 12). Through her work she openly embraces her identity as a lesbian and refuses to hide her body after undergoing a mastectomy.

Lorde had to witness what can be called “Anxiety of Authorship”, especially as a Black woman who could not be considered conventionally beautiful. Not only did she face the horrendous discrimination from White men, but also from Black men who preferred light-coloured skin or thinner women.

In The Cancer Journals, cancer is essentially a metaphor for the struggles of being poor, Black, and female. She associates her illness to the fears and hardships she faced throughout her life, from childhood to adulthood. The chapter, “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action” reflects Audre Lorde’s struggle with cancer diagnosis.

Also Read: Word of the Year Brain Rot: The Sign of our Times

In this deeply personal and confessional work, she confronts fear, trauma, and social taboos, including suicidal thoughts. Lorde highlights how unspoken pain offers no protection, emphasizing the impact of mental distress, often suppressed by societal expectations (Freud 504).

Her greatest achievement lies in transforming personal suffering into powerful art, capturing both its raw intensity and deep emotional truth. Her work explores the connection between language and the unconscious mind. Her work indulges into the realities of life and introduces new ideas of self-expression and identity. She focuses on the concept of Sigmund Freud – “Id” – the hidden desires, fear, and anxieties that people express through gestures, sounds, art, and writing.

In The Cancer Journals, Lorde uses storytelling as a way to take control of her experience and turn it into something powerful.

Lorde wants people to understand that the systems they trust– like the healthcare industry–do not always work in their best interest.

“It should be noted that research being done on this potentially life-threatening practice represents time and research money spent—not on how to prevent the cancers that cost us our breasts and our lives—but rather upon how to pretend that our breasts are not gone, nor we as women at risk with our lives.” (Lorde 78)

Like many other diseases, breast cancer is deeply connected to politics and shaped by societal views, for example, the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 1990s. Philosopher Michael Foucault delineates modern society that treated health as a civic duty. If someone falls ill, they may face different forms of control or judgement.

Lorde argues that women must take responsibility for their own health.

Society often prioritizes appearance over survival in breast cancer treatment, as seen in The Cancer Journals, where a doctor implies that without an implant, a woman’s survival is almost irrelevant because “breast is the sign of feminine beauty” (40).

Lorde rejects this notion, refusing a silicone breast to challenge society’s rigid expectations. Her stance represents a fight against ingrained societal norms (Freud) and a pursuit of self-actualization beyond imposed ideals. As she states, “I am a post-mastectomy woman who believes our feelings need voice to be recognized, respected, and of use” (Lorde 6).

It is observed that several writers incorporate metaphors, military metaphors, when discussing illness, especially in the Western World, as they consider fighting in a battle to be the most superior example of strength. However, when introspecting Lorde’s experiences with Breast Cancer, it is evident that these war-like comparisons would rather make it more difficult for one to deal with the disease.

Lorde makes one wonder or question whether the idea of being a “warrior” or a “fighter” is the ideal way of speaking about illness.

For Lorde, seeing herself as a warrior is not something that appeals to her. She doesn’t not exactly interpret her illness as a fight. What truly helped her cope was writing. However eventually she does implement a war metaphor in The Cancer Journals where she paints a picture of Amazons– the female warriors from Dahomey who were known to have removed their breasts to become better archers.

Lorde’s words echo like a battle cry, not for war, but for truth—a defiant refusal to let silence shape her story, constantly reminding every woman to not keep that “voice” suppressed. Through her struggle of storytelling, she reminds us that survival is not about conformity, but the courage to live unapologetically.

* * * * * * *

References:

Alexander, Elizabeth. “”Coming Out Blackened and Whole”: Fragmentation and Reintegration in Audre Lorde’s Zami and The Cancer Journals.” Oxford University Press, vol. 6, no. 4, 1994, pp. 695- 715.

Gupta, Rakhi, and Richa Arora. “In the Castle of My Disease: an In-depth Study of Lorde Audre’s The Cancer Journals.” Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (, vol. 11, no. 3, 2019, pp. 1-9.

Khalid, Robina Josephine. “Demilitarizing Disease: Ambivalent Warfare and Audre Lorde’s The Cancer Journals.” The Johns Hopkins University Press, vol. 42, no. 3, 2008, pp. 697-714.

Leonard, Keith D. “”WHICH ME WILL SURVIVE”: Rethinking Identity, Reclaiming Audre Lorde.” The Johns Hopkins University Press, vol. 35, no. 3, 2012, pp. 758-777.

Lorde, Audre. The Cancer Journals. Penguin Random House, 2020.

Sipyinyu, Njeng Eric. “Audre Lorde: Black Feminist Visionary and “Mytho-poet.”” Revue LISA e-journal., vol. 2, no. 4, 2004.

Image Courtesy: Amazon

Audre Lorde

Sangsthita Banerjee is an Undergraduate student majoring in English at

Jogamaya Devi College, University of Calcutta. Her interests include

Postcolonial literature, Indian diasporic narratives, and Partition literature.