It is interesting to note that the piece Antonioni sat down to draw on the morning of 30th September was a remake of the one he had offered for the cover of the album marking “Silence in Colour’. Only instead of his favourite herbal green, this was in black. And like the piece for the cover this also was not to be filled in with colour.

As the drawing grew from range to range and moved from base to top in slow motion, it filled the space with a design Antonioni prefers to identify as a rhythm fixed in signs. The rhythm, Antonioni had written in 1963, is in the slow uncovering of a static reality. Which is the prime concern of a painter. For a director the problem, however, is in ‘seizing a reality which matures and consumes’. And to propose that movement that arriving and following, is to achieve a new perception.

Watching Antonioni’s fingers moving on the canvas is a treat in itself. He is building up a linear movement that is stored in his mind from an earlier execution. It is not a figure from life or a pattern from geometry, but a tracing from memory of a structure that has already impressed itself on his mind as the body of a meaning. It isn’t worthwhile to ask what meaning it supports, for—as per Antonioni’s credo—a meaning only awaits the uncovering of a further, if not necessarily a deeper, meaning. Watching the maestro revisit a form from memory through the camera lens of Nemai Ghosh one is tempted to put a second title to the one it famously sports (Silence in Colour)— ‘Total Recall’.

Who knows, if filled in with luxurious acrylic colours, it wouldn’t turn out into a remake of his splendid study of floral plenty ‘La Cornucopia’? In most of his designs—a careful study of his works shows—Antonioni leaves his options open till the moment of choice sieges him. The moment of choice is when colour is applied to the drawing. Alessandra has a beautiful anecdote about this. She writes, addressing Antonioni…

“Maestro, I remember when I timidly tried to direct your movements and you maliciously underlined my discomfort by pointing your finger at my forehead, as if to say, “You don’t understand.’ And then Enrica suggested, ‘You have to embody his shapes; that is what he wants.”

Then Alessandra puts herself in the master’s moment of choice and writes, “I find myself once again amazed assisting in your creative act: the white canvas, your fixed gaze focusing on that portion of space, as if wanting to surpass it.

This is the most important moment, a brief yet eternal instant because it appropriates itself from that vast and precious visual heritage which travels through history and exacts its place.

When you are ready you let me know, you want my attention, then you begin and I do not know when you will finish the gesture that is born as a mark, becomes form, and then constructs space. And then you say, ‘That’s enough.’…sometimes it is the colour itself that gives you the idea of a shape and we play at recognizing the form as human or animal, or as strange silhouettes in the city, or mysterious writing.”

“Our communication is made up of gestures, and yet this corresponds to a rich and porous dialogue which conveys substance. I become the instrument for manifesting your abstract space and colours. The beautiful thing is that one can never predict how your paintings will end up, Maestro; you always reserve a surprise for us when you do not want to let one of your brilliant intuitions get away.”

Also Read: Painting Films: Antonioni’s Brilliant Use of Cinematic Colour

In Nemai Ghosh’s collection, we do not have the maestro masterminding the application of colours; perhaps he wished it that way. Sheer drawing it seems became at times the be all and end all of his artistic aim—reducing everything to a basic minimum, cutting out the clutter of speech and celebrating the silence. Even the colour each person saw was an object we believed differed in tone or shade. A condition—impossible to prove—that prevented colour from being absolute.

The itinerary of Antonioni’s crayon on the canvas reveals an interesting feature too. He first puts his pencil at nearly the base on the left side like the classic camera movement from the left of the image to be grabbed by the fingers that slowly move to the right and then in reverse move rise upward and backward as if on the crest of a wave.

Now his second take off from close to the left range to strike a couple of sharp angles and return to a second wavy flow rightward. The wave, however, breaks and is reduced to a shimmering dripping line heading to the edge. The line then spirals up to take possession of the upper reaches of the canvas. It is like Antonioni shooting open spaces.

It all ends with Antonioni signing the piece; and after the easel has shifted stretches his hand to Eurica’s and look silently into her eyes. It reminds Nemai of the morning in the Kolkata hotel room twelve years ago. When Eurica hugged her husband from behind and Antonioni looked to a side with a glimmer of a smile on his markedly brooding visage.

Nemai also has master’s smile at the birthday party. But the shot that takes one’s breath away is the black and white study of the maker of ‘The Cry’ against a painting titled ‘Fire’! What decided for Nemai the black and white exposure of a painting as stentorian as ‘Fire’ I have no clue to, since Nemai himself hasn’t any. What, curiously, accentuates the loneliness of the image is the massive pillar at the back and the deserted look of the rear part of the hall. One is almost tempted to ask: What is the master thinking? Or looking at?

Yes, ‘looking’ is the concern of most of the portraits Nemai secured of Antonioni in those three days of September 2006. It breaks my heart to call attention to what he had sadly and revealingly stated about his tryst with destiny and with what he had signed off in his brochure for “Silence in Colour” He wrote…

“My craving to look is that which will consume my eyes in the end, and this wearing down of the pupils will be the disease that will kill me.

One night, I will look so fixedly at the darkness that I will end up inside of it.”

Image Courtesy: Wikipedia, 28 Piazza di Pietra, WordPress, Arte Magazine

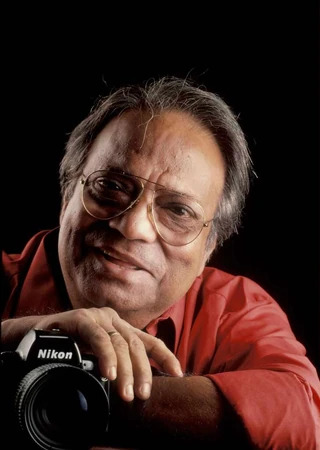

Shankarlal Bhattacharya

Born on 15th August, 1947 in Kolkata, Sankarlal Bhattacharya is a gold medallist in English Literature. He received his training in journalism from Paris, immediately after which be forayed into the world of writing. He has worked as a journalist in the Anandabajar group and has over 130 books to his credit. Aside from short stories and novels, he has written biographies for Ravishankar called "Raag Anurag", for Bilayat Khan called "Komal Gandhar" and has also been the co-writer for Hemanta Mukhopadhyay's memoir "Amar Gaan-er Sorolipi". He has translated widely from Shakti Chattopadhyay's poems to Satyajit Ray's screenplays