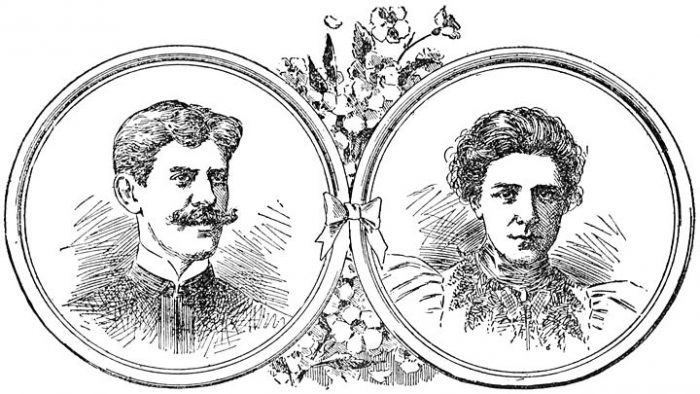

June 3rd is celebrated across the globe as World Bicycle Day. American cyclists Mr & Mrs H Darwin McIlrath traveled around the world on their bicycles in the late 19th century. Their travel experiences were compiled in a book titled Around the World on Wheels, for The Inter Ocean: The Travels and Adventures in Foreign Lands of Mr. and Mrs. H. Darwin McIlrath (1898) from the letters published in ‘The Sunday’ and ‘The Inter Ocean’ from 1895 to 1898. Their travels was sponsored by the Chicago ‘Inter Ocean’ newspaper. The tour started from Chicago on 10 April 1895. As a special feature on World bicycle Day, we publish excerpts from their travel in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Benares in India, with original illustrations from the first edition. It is interesting to observe the white supremacist views expressed here about Indian religious practices.

Two years to a day after leaving Chicago we walked up the gang-plank of the steamship “Africa,” booked for Calcutta, only three days across the formidable Bay of Bengal. Mrs. McIlrath developed her usual attack of sea sickness, though the water was unruffled, and was kept in her cabin for the entire voyage, leaving me to occupy the daylight hours wandering among the deck passengers. The first impression one receives on landing at the port of Calcutta is that the city is one vast cab stand. “Gharries,” as the natives’ hacks are called, line the walks, crowd the streets, rest under the shades of trees in parks, and stand at the curb in front of hotels and shops. The dust, rattle and bang caused by these shaky, dirty vehicles, which are dragged about by horses at snail’s pace, is a nuisance second only to the tram cars, and one which would be tolerated only by custom-bound, “strictly-in-form” Englishmen. Streets in Calcutta wander aimlessly along, similar to the rail fences in Indiana, and the buildings, uniformly of staff-covered brick, are of every imaginable size and shape, as if architects were of one mind in determining to try all kinds in an effort to obtain one adapted to the climate. Sidewalks, roads and paths are packed with white-clad natives, barefooted and bareheaded, in the awful glare of heat, which strikes horses dead, unless their heads are protected, yet none of the blacks appear to suffer. Doors of hotels and shops are kept open, but hanging in the apertures are heavy mats of a peculiar grass, which coolies wet with pails of water, and by which means the air is cooled. Everywhere the heat is talked about and guarded against, and yet, with huge fans swung constantly over one’s head, with cooling draughts on a table by your side, the perspiration pours from every part of the body. One hundred and ten degrees in the shady corridors of the Continental hotel, the coolest in all India, 98 degrees at night, and this was the country we crossed on bicycles, involving over 2,000 miles’ travel, and beyond the pale of ice or daily clean clothes! Bicycles are ridden extensively in Calcutta, comparatively speaking more than 3,000 wheels being enumerated in the tax list at the time I was in the city. There are, however, only about three months in the year favorable to riding—December, January and February. In other months cycling is tolerable only between the hours of 5 and 8 in the morning and evening. This, of course, applies only to the Europeans, and not to the natives, who ride in the intense heat of midday without the slightest difficulty. A sight calculated to arouse laughter in a wooden cigar sign is one of the proud possessors of an old solid-tire, with hammock saddle and wide handle-bars, as he plows along the road, making erratic dives, like misbalanced kites.

The most frequented road is a short strip on the Maidan, an enormous clearing, five and seven-eighths miles in circumference, in which is situated Fort Williams. Roads of fine macadam skirt the [87]park, and amid cricket, golf and football grounds are statues and columns erected to Englishmen who have performed satisfactory duties in India. Eden Garden, at one end of the Maidan, is a beautiful spot, and here, morning and evening, a well-directed band plays sweet music to charm Calcutta’s conglomerated inhabitants. Cycling in early evening along the Strand is also gratifying. The street is crowded with women in white and red robes, silver anklets and bracelets, their head and matchless figures but faintly concealed by flimsy togs. Burning ghats are also erected on the river shore. The Calcutta burning ghats on the Strand road affords accommodation for the cremation of sixteen bodies simultaneously. In appearance, the crematory is unpretentious, simply a low-roofed structure divided into an alcove, and two waiting rooms for mourners. The Inter Ocean cyclists visited the crematory, and were shown throughout the establishment by an aged Hindoo, who superintended the force of men who kept going the coals under fifteen pyres. Not of less interest, but far less disagreeable, is a distinctively Calcutta feature. Kali ghat. This is a temple devoted to Kali, goddess of destruction, reputed in Hindoo lore to possess a thirst for blood, and to appease and propitiate whom live sacrifices are made. Formerly human beings were offered, but under British rule the custom was abolished, and kids and goats substituted. Decapitation is the method offered, and as fast as sacrifices are brought forward, the bleeding little things are seized by the ears, the priest makes a cutting slash with a heavy knife, and the headless trunk is thrown to the ground. We witnessed the religious rites of Japanese and Chinese, and we had seen the medicine-dances of the American Indians, but nothing approaches the furious fanaticism and the frenzy of the Hindoo at Kali ghat. Men shouted themselves hoarse, women screamed and tore each other’s clothes at the shrine of the goddess. It took the assistance of half a dozen hired blacks to force for us an entrance into the temple, and rushes of worshipers were so great that thrice we were swept back ere we obtained a glimpse of the hideous deity. Her face and figure a blood red; with multiple arms swaying like the tentacles of an octopus; her face distorted with blood red tongues; a necklace of skulls about her throat, the goddess Kali is indeed the representation of destruction. Gross, hideous and repulsive as was the figure, the effect was heightened by the maddened crowd, who, with wild shrieks, tossed offerings of flowers at the fiendish idol in their effort to escape from the calamities, believed in their pagan minds, to be brought about by neglecting to satiate the goddess’ greed for bloodshed and crime. Amid such surroundings it was not to be wondered at that our minds reverted to the fact that “ghazi,” the assassination of Christians, is still in vogue in India, [88]and that one of the devout worshipers might easily plunge a knife in our backs, and thus earn his way to Hindoo heaven with ease and glory. I can assure my readers that we felt easier and more comfortable when once more in our gharry and the horses on a dead run en route back to the hotel. We learned from a priest at the ghat why Calcutta is so named, the title being a British corruption of Kalikata, the name bestowed by the Emperor Akbar, in 1596, in commemoration of the proximity of Kali ghat. We were in Calcutta two weeks before the cycling fraternity knew of our arrival. When they finally discovered our presence, we floated along on a wave of popularity. Cyclists, dealers and agents were our daily companions and callers. American machines were well-known and liked, and wood rims and single-tube tires were looked upon with doubt, but after an inspection of the hardest-used pair of wheels the world ever knew, wood rims and single tubes took on the ascendency.

NIGHT RIDING THROUGH INDIA TO ESCAPE THE HEAT—THREE IMPUDENT ENGLISH WHEELMEN ENCOUNTERED AT BENARES.

We left Calcutta early on the morning of May 4, taking the Strand road, across the sacred Hoogly river by means of the Jubilee bridge. We were accompanied for a brief distance by Mr. W. S. Burke, editor of the Asian, the only legitimate sporting paper in the East. To this gentleman were the Inter Ocean tourists indebted for maps, guidance and excellent entertainment while in the city. He piloted us through a road shaded by magnificent palm trees, an avenue 40 feet wide, level as a billiard table and smooth as asphalt. Mr. Burke informed us that this was the “Grand Trunk” road, our path across India from shore to shore. Most of our riding was done at a fast clip, in spite of the fact that we carried full luggage cases, camera, guns, water canteens, lamps, and bells to the extent of 50 pounds each. Only twice did we dismount in the twenty-five-mile run to Chandernagore, once to induce a cautious gate tender at a railroad crossing to open the gates, the second time to view the terrible cars of Juggernaut. Much has been written concerning these vehicles and the manner in which they are hauled about on festive occasions, and in former days crushed out the lives of hundreds of devout fanatics, who endeavored to reach heaven by self-sacrifice. One would naturally believe that such barbaric practice had been done away with by British rule, but such is not the case, and, despite the presence of police and soldiery, each time the towering car is hauled out by worshipers some poor, weak-minded wretch hurls himself under the ponderous wooden rollers.

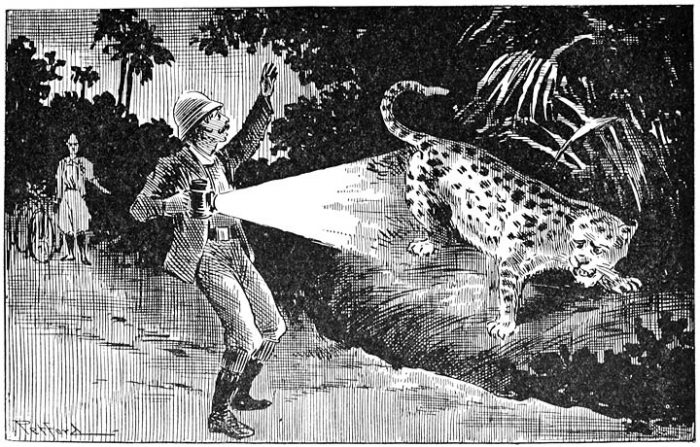

Burke, good-natured, fat and jolly, left us at Chandernagore, but not before a breakfast at the same hotel where, three years ago, he had breakfasted with poor Lenz, served by the same woman, who spoke also of “the fine little lad” who was lost in Armenia. Intense heat made riding dangerous during the day, and after we left Burdwan, on May 5 (81 miles from Calcutta), the greater part of our progress was accomplished at night. We never realized what Indian heat signified until now. The coolness of night offers many inducements for bullock-cart caravans to travel, and a sharp outlook has to be maintained for these obstacles. Our arrival at the Hotel de Paris in Benares, on May 12, completed one-fourth the run across India, a total of 496 miles from Calcutta, representing a succession of night rides, with stops for refreshment and rest at the bungalows along the route. Night riding in India is the only way to avoid paralyzing heat, but it has its terrors and dangers, and after some of my experiences in the jungle between Delhi and Benares, I should say that if I had the trip to make over again, I should undoubtedly trust to the mercies of the sun. We encountered leopards by the score, and though leopards in India are not supposed to attack humans, we could not help our misgivings at the sight of the graceful creatures, as they silently bounded their way through the jungle.

Also read: The Assault on Mount Everest 1922: Excerpt

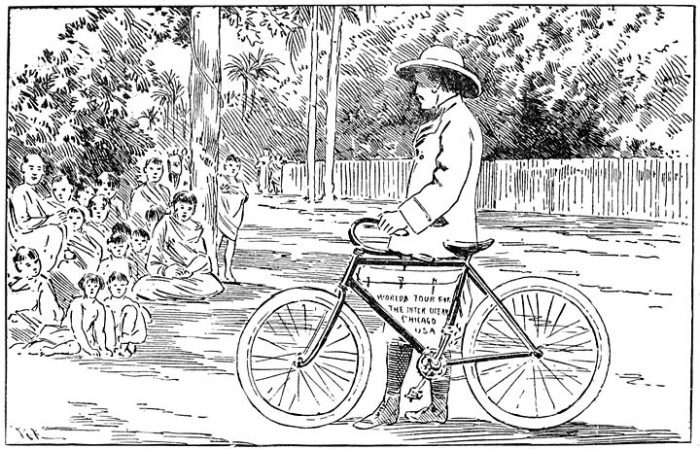

Our arrival at the Hotel de Paris caused much excitement. The English do not read newspapers as generally as do the Americans, and, with but one exception, not one man around the hotel had the slightest idea who we were, where we were from, or what we were doing. In fact, after reading the “World’s Tour for the Inter Ocean, Chicago, U. S. A.,” as printed in large white letters on our luggage cases, many asked us politely, “Pray, what is the meaning of the legend?” We had learned while in Calcutta that Messrs. Lowe, Lum and Frazer, who had left England on a cycling tour of the world in 1896, were on their way across India, and that in all probability we would meet them in Benares. We looked forward with much pleasure to the occasion of joining hands with cyclists who understood the hardships of great journeys in strange lands, but the meeting occasioned us an unexpected set-back in our natural affection for fellow wheelmen. The trio arrived on the second day of our visit in Benares, and immediately sent word that they wanted to see me. I called upon them, and was greatly surprised to ascertain that they looked upon Mrs. McIlrath and myself as frauds. They questioned me closely as to my journey, and concluded by commenting upon the strangeness of the fact that they had never heard of us before. This I did not regard as unseeming, since few of the inhabitants of “the tight little isle” do know what is occurring in the greater part of the world not under British taxation. Fifteen minutes’ conversation with the Frazer outfit convinced me that the new aspirants to globe-girdling honors entertained little respect for Americans in general, and ourselves in particular. Lenz they declared emphatically a nonentity in cycling history; Tom Stevens was totally unreliable, and as for ourselves, we had undergone no hardships, and were comparatively new. They probably did not like Stevens because he was the original “round the world on bicycles;” Lenz because he had accomplished single-handed more up to the time of his death than these fellows could accomplish over the route they had selected, if they completed their program; and Mrs. McIlrath came in for her share of contempt because a wee, slender woman, she had encompassed what they averred they would attempt, in a number strong enough to cross the threshold of any earthly inferno with impunity.

To read the full e-book please visit ProjectGutenberg.org

American cyclists.