Parallel cinema was not the talk of the town prior 1970. The template of filmmaking did not have a stringent surface, and its layers could be explored by a tenth-fail director (not a scale of judgment), K. Asif (Mughal-e-Azam) to someone like Tapi Chanakya (Ram aur Shyam). Cinema before this particular time period was more about nation love and the desire to remain in a certain dementia by covering reality. This is where India got to witness the birth of Shyam Benegal, who after the demise of the maverick we know as Guru Dutt, for the very first time, touched the wounds of a post-colonially confused and depressed moment of this civilization.

ANKUR

His debut film, Ankur can be considered as one of the first films with a non-linear narrative. The marriage of Govind Nihalani (cinematographer) and Shyam Benegal, as the director, spoke about the complexities that reside under the umbrella of casteism, conservatism and softcore despotism. Benegal tracked down the main reasons behind this particular depressing period of India, which happens to be a continuation of the oppressive psyche of the country even before its independence.

Ankur highlighted the dominance of the male gender and the toxicity it breeds to overrule freedom of thoughts and desires.

In many of its parts, Benegal also points out how the same factor is responsible for the growth of a new generation without any change in psychology. The necessity of the hour was to push the weak nerve of the people of the country. Or else we might have listened to an entire population singing “ye duniya agar mil bhi jaaye toh kya hai”.

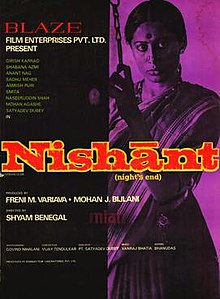

NISHANT

It is not an easy task to speak about a sensitive topic like obsession, greed, sexual freedom and oppression against women without a good script. Vijay Tendulkar and Satyadev Dubey’s ambitious skill got firm in the film industry after the release of Nishant. Benegal’s second project largely spoke about the obsessive necessity of greed. Little does anyone care about the vision of Shyam Benegal for the actors he prepares for the camera.

Nishant magnified the perception towards actors like Om Puri, Naseeruddin Shah, Anant Nag and Amrish Puri.

It was needed especially when the audience aligned their choices towards the deliverance of the star actors like Dev Anand, Rajesh Khanna, Dharmendra and all, more than that of character actors. The film also showed the plight of women and dared to put a finger in the eyes of a country that had a hardcore belief in independence and democracy. Violence, in text, can be easily described without shedding a drop of blood literally. In a film, if a director does the same, the finesse lies in unfurling mental chaos. Shyam Benegal’s violence crawls through our ignorance and manages to torment our ideal thought.

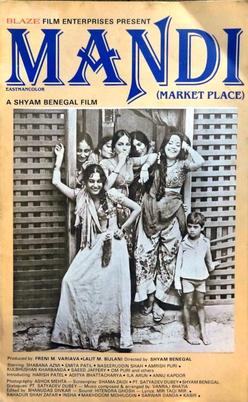

MANDI

Before Bhansali’s Gangubai, Anurag Kashyap’s Dev D or Srijit Mukherji’s Rajkahini, an Indian film that did not hesitate in putting erotic references and romance with the bazaar of prostitutes is Mandi. We, as a conservative population, developed our minds towards marginalizing sex workers. Irony lies in the fact that in the epic of erotica Kamasutra, the one who introduces kings, politicians, and any random man or woman, to his/her body is a mistress (an appropriated and toned-down term for prostitutes). Erica Jong, in her fictional memoir How to Save Your Own Life mentions the essentiality of exploration of the human body allowing most men of the libertine thought and even beyond, to become good sexual partners.

Shyam Benegal’s Mandi deals with the growth of desire for love in the mind of sex workers.

But it cannot be denied that the script had a negative approach towards women living in the brothels. Yet the director’s vision was to keep a mirror before the most ideal lovers of society and how patriarchy operates from a very subtle dialogue like ‘tumhe iss gandi jagah par rehne ki zaroorat nahi hai…chalo hum kahi bhaag chalte hai’. Sushil is an ideal human being and his love for Zeenat stays dissociated from her profession. Tungrus, played by Naseeruddin Shah, maintains his love for the head of the brothel, Rukmini Bai (played by Shabana Azmi) irrespective of what she pursues. Mandi stands out for nakedly speaking about the topics of gaslighting, appropriating the choice of women and fabricating a woman’s wants and desires in the name of traditional hypocrisy.

Also Read: Tapan Sinha: A Centenary Tribute

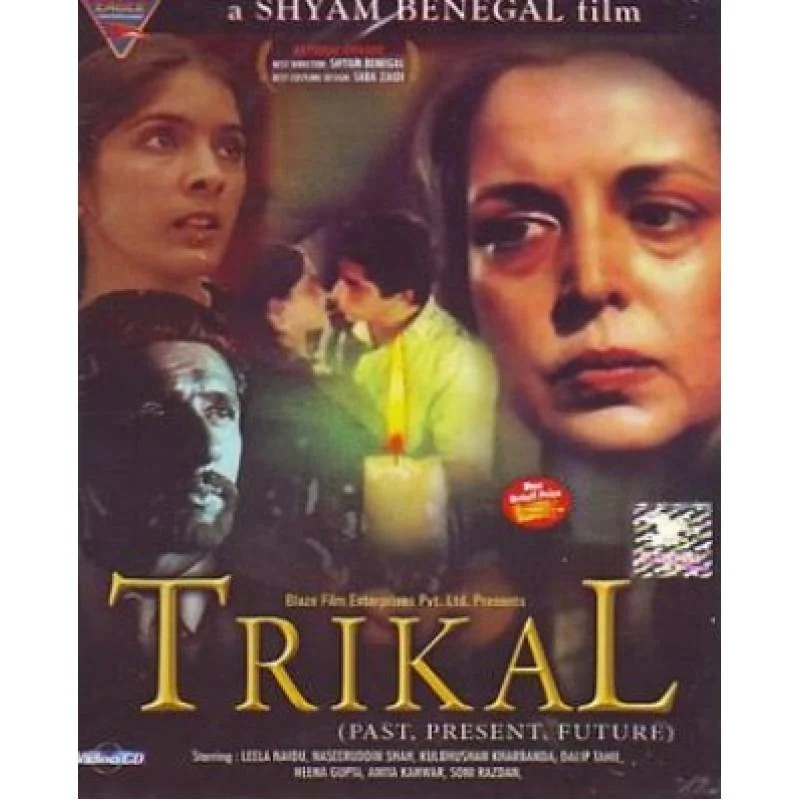

TRIKAL

We get adhered to a family. They greet us with a smile while we cry. But the scars they leave on us is something we always choose to not spill out. Often our darkest and most inappropriate thoughts and act is a consequence of the equation of our family. Shyam Benegal’s Trikal is all about the secrets of a family and how the psychological horror of the past can cast a shadow on the present life.

Its take on infidelity is something that stripped the veil most directors of the past wanted to keep.

The film also deals with the idea of shame and morality in a family. If we have to transfer the story to the contemporary time, we will find that from the murder of a foetus to the gossip about a woman opening before a man other than her husband still is a hot cake. In Bengali culture, when we speak about Trikal Dush, we always associate with something negative of the present that is going to haunt our future. Trikal also happens to be associated with Shiva (a one-woman man). For a woman, even today the concept of Trikal Dush is associated with her body, relationship and the duty to become a mother.

Shyam’s film equally speaks about the shame infidelity can cause even in a matriarchal family involving some of the boldest women.

Unplanned or accidental pregnancy is the equator of the film that forces the female protagonists to stay silent and submissive. It is not the responsibility of a filmmaker to change the society. But like every other artform telling a story which triggers the dormant conscience of society becomes a necessity. Shyam Benegal’s Trikal took a controversial and weird topic and puts a few questions before us: How is the past related to the present? Why is the choice of women a matter of shame? How can desires break the enormous boundaries of a tradition built upon unquestioned conservatism?

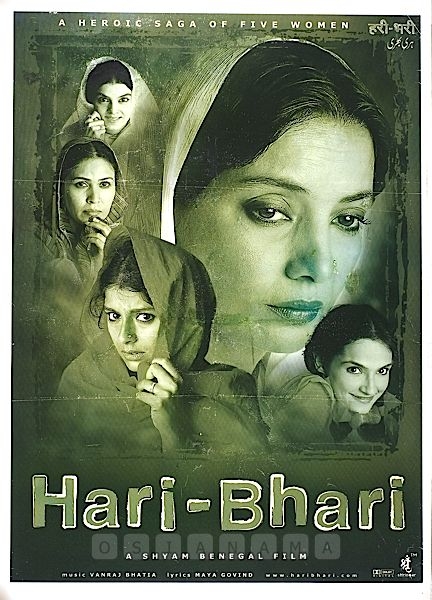

HARI-BHARI

A story on fertility has always been for the closed rooms. Men still maintain a certain distance from the concept since the cultivation of gender discrimination has been so fertile. Shyam Benegal’s Hari-Bhari is about a woman who is dominated and assaulted by her husband and her in-laws for not being able to give birth to a male child. Society has not changed even a little. The same ‘tradition’ is still being nourished in urban and rural homes. Money and education still fail to overrule the toxicity that men learn from their families.

Shyam’s focus on how religion and its fabricated knowledge acts as a determining factor in brewing oppression made it a controversial film with the title of disaster in the box office even after it won the National Award.

The new age filmmakers who choose to work on the topic of fertility and the additional references that come with it consider the screenplay as a template. Even in the age of AI, the nation is not ready to accept a film that addresses a topic that’s a daily news since talking about a woman’s body is hailed as obscene and sinful.

Shyam Benegal turns ninety this year and in an interview with Samdish Bhatia a month ago, he did not refrain from saying that he has a film in his mind and wants to make it irrespective of how the audience is going to accept the project. The man changed the style of filmmaking and the vision of storytellers who want to speak through motion picture, that is, cinema. We did not celebrate Guru Dutt when he was alive. Celebrating his disciple is the need of the hour.

Image Courtesy: Wikipedia, Pinterest

Kabir Deb is an author/poet based in Karimganj, Assam. He works for the Punjab National Bank and has completed his Masters in Life Sciences from Assam University and is presently pursuing his MCW from Oxford University, London. He is the recipient of Social Journalism Award, 2017; Reuel International Award for Best Upcoming Poet, 2019; and Nissim International Award, 2021 for Execellence in Literature for his book 'Irrfan: His Life, Philosophy, and Shades'. He runs a mental health library named 'The Pandora's Box to A Society called Happiness' in Barak Valley. He reviews books, many of which have been published in magazines like Outlook, Usawa Literary Review, The Financial Express, Cafe Dissensus, Sahitya Akademi, etc. He currently also works as the Interview Editor of the Usawa Literary Review.