Neelajana Ghose is a leading Kantha revivalist from Kolkata whose love for the craft has its roots in Santiniketan. She started off as a costume designer in films and continues to work in that field. She has worked in films like Chittagong, Paar and Shankhachil among others. She imbibed her love for Kantha from her mother Sreelata Sarkar who has played a significant role in the revival of Kantha. In this interview she extensively talks about Kantha as a craft— its origins, traditions and social impact on artisans (mostly women in this case) for the readers of thespace.ink.

Q. How long has the craft of Kantha existed? How old is it?

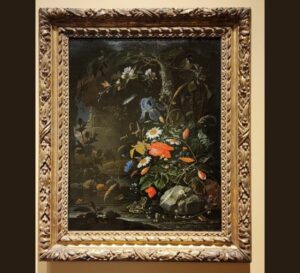

A. The sewing techniques of piecing, appliqué and quilting have been used for clothing and furnishings in different parts of the world for several millennia and a wide range of quilting styles and techniques has uniquely evolved around the globe.

The earliest known quilted garment is depicted on the carved ivory figure of a Pharaoh dating from the ancient Egyptian First Dynasty (C:3400 BC). In 1924 archeologists discovered a quilted floor covering in Mongolia (app. between 100 BC and 200 AD). Quilting can be considered one of the earliest examples of up-cycling as it is made with worn-out old fabric which is morphed into new products.

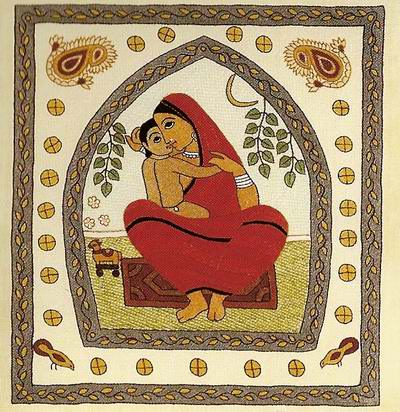

Kantha is one of the oldest forms of embroidery originating from India. Its origins can be traced back to the pre-Vedic age. It is a particular form of quilt that is a centuries old tradition. Initially women from all sections of village society used old sarees, dhotis and lungis generally in three layers and made kanthas to be used as covers to protect their families from cold.

In order to distinguish between ordinary Kanthas and embroidered ones, ‘Nakshi Kantha‘ is a term that may be used to differentiate the latter from the former.

This art form disappeared in the early 19th century and was revived in the 1940s by Pratima Debi, the daughter-in-law of the great Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore. After the Industrial revolution Britain imposed draconian taxes on imports of Indian textiles into Britain, while levying drastically lower taxes on British textiles that were imported into India. This strategy quickly reversed the balance of trade between Britain and India. With five strategies – price fixing, violence, taxes, innovation and strategic theft, it’s easy to see how Britain crippled India’s handloom industry. With the decline and unavailability of handloom textiles the tradition kantha craft also declined. Its revival was disrupted again during the partition of India in 1947. After the Bangladesh War (1971), Kantha was reborn.

Q. How did kantha embroidery evolve from the original?

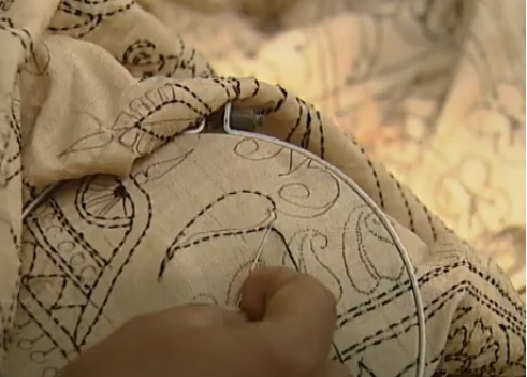

A. I think there are parallel trends in Kantha embroidery now. There are women who still make kanthas in the traditional way – three layered old fabric with various motifs and quilting. There are layered kanthas made from new fabrics and there are kanthas of single layers of fabric that have a particular kind of embroidery.

Earlier, Kantha making did not have a commercial angle. Traditionally they were made as gifts for a daughter or any close or loved person. When we discuss handicrafts, if we maintain an orthodox point of view of keeping the art form ‘pure’, the form will gradually decay and disappear in this world of globalisation. I believe that if we can keep the artistic aesthetics of the form and continue our efforts to develop the form it will sustain and survive the ravages of time. We need to make kanthas saleable as well as maintain a demand for the products. Use of new fabric will make them long lasting.

Q. Traditionally what are the different types of Kantha? How are they different from each other? Other than the running stitch embroidery, what other styles of stitching are used in Kantha? What are the commonly used motifs?

A. Kantha generally means quilt or wrapper. All products made by quilting in the traditional way can also be called Kantha. In order to distinguish between ordinary Kanthas and embroidered ones, ‘Nakshi Kantha‘ is a term that may be used to differentiate the latter from the former.

Different types of Kanthas:

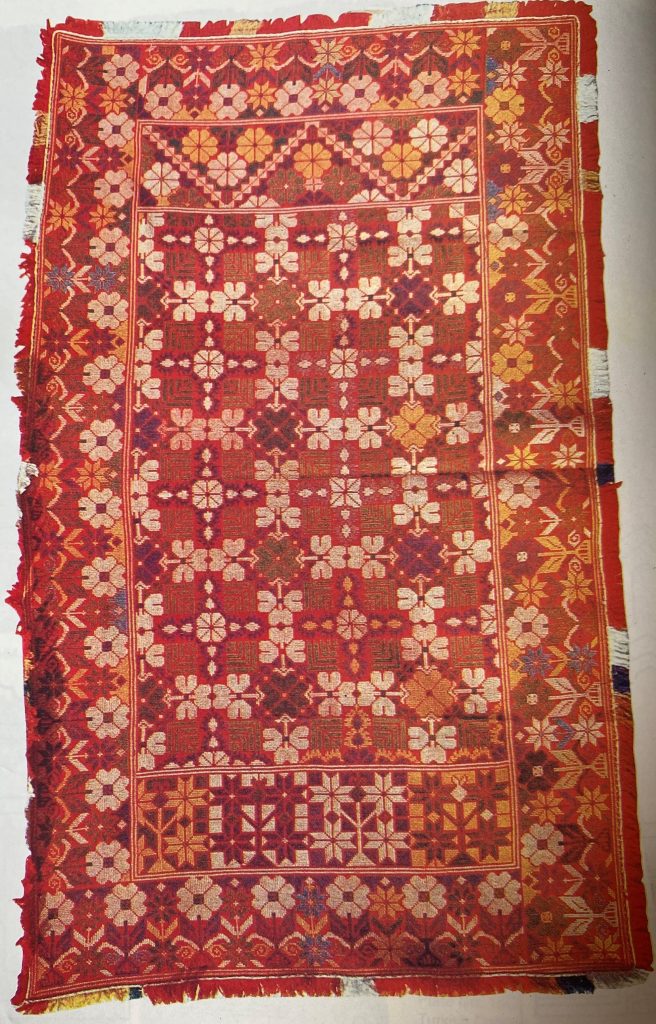

Sujni Kantha – These are elaborately embroidered and used as spreads or coverlets, measuring about 5 by 6 feet and have three layers of fabric.

Lep Kantha – These are thicker kanthas perfect for winter use and larger than Sujni.

Ashton Kantha – These are smaller, square or rectangular kanthas used as spreads for pujas, or for special guests or the bridegroom to sit on.

Jainamaz – These are Muslim prayer rugs.

Palkir Topor and Khat Kantha – Palkir Topor were placed on top of the palanquin and the Khat Kantha inside it.

Bayton or Bostani – These square Kanthas are meant for keeping books or other valuables upon.

Arshilata – This is a small rectangular Kantha used for wrapping toiletries. It has a tassel at one end so that the articles can be rolled and tied up.

Oar, Balish Kantha – This small, square or rectangular Kantha is meant to be placed on the top of a pillow

Gilaf – This envelope shaped Kantha is meant for covering the Quran. A smaller version of this is the Botua, Durjani or Thalia used as a wallet or to wrap betel leaves in.

Dastarkhan – This is a long narrow Kantha used as a runner for an eating place. Like the Jainamaz and the Gilaf, this is also a Muslim Kantha, from about 10″ to 18″ wide. The length depends on the number of people seated at a table.

Children’s Kantha – This kind varies from very small ones for the newborn to larger ones for toddlers.

Rumal Kantha – This is a small square Kantha used for covering plates

Different types of stitches used in Kantha :

Besides the running stitch, the chief stitches used are darning stitch, satin stitch and loop stitch. For the outlines, stem stitch and split stitches are used. For quilting a small running stitch is used. In contemporary Kanthas we find different kinds of stitches drawn from other traditional Indian embroideries. This sort of adaptation has added a new dimension to the skill of kantha-making and the subsequent products.

Commonly used motifs in traditional Kanthas:

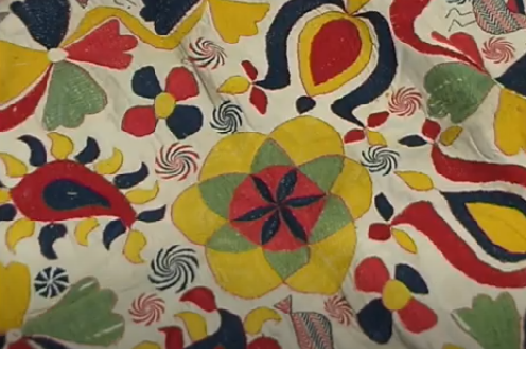

Different kinds of leaves, creepers, flowers, birds, animals, fish, human figures, household articles, gods and goddesses are used as motifs for kanthas. In Muslim Kanthas motifs of human figures, gods and goddesses are not seen. The motifs are selected by the creator and are inspired and drawn from objects she sees in her everyday life. At the center of most of the earlier Kanthas, there would be a lotus. There is a square or rectangular outer border, the Tree of life or kalka on four corners. Between the centerpiece and the outer borders there will be all the other motifs that the artisan wishes to depict.

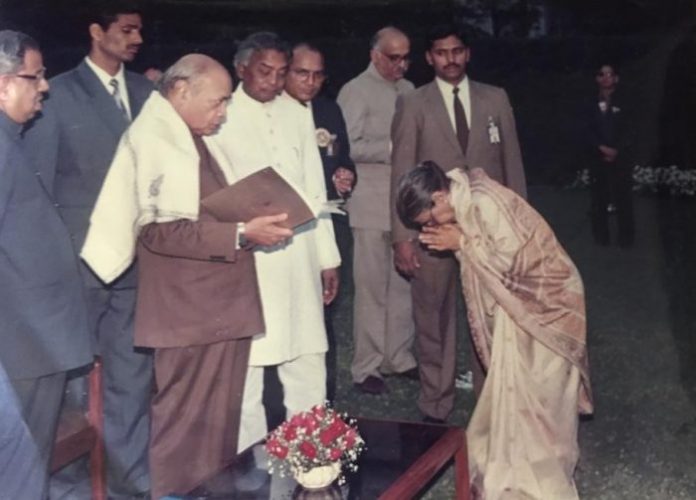

My mother Smt Sreelata Sarkar got admitted to the two years’ certificate course for women, Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan in the early fifties. She also had a personal association with Pratima Debi. Her daughter Nandini was a close friend of my mother.

Kantha designs and motifs have evolved very interestingly with time and the exposure of the Kantha artists to the world outside of their own milieu.

The uniqueness of the Kantha design is its openness towards including any kind of image as motif – be it an aeroplane, a television , chinar leaves, motifs from other folk art, such as Madhubani, Patachitra, folk painting and textile motif from different parts of the world.

Q. Since when has this craft been introduced on sarees and other pieces of clothing? In Santiniketan how did the women take it up as a means of livelihood? What are the textiles most suited for this embroidery?

A. As far as I can remember after the Bangladesh War this initiative was taken up to enhance financial support for the family and maybe a few years later this art form became more widely practised in West Bengal. The initiative was similar in Santiniketan as in other parts of West Bengal. The number of women involved in an organized way is very commendable.

The most suitable fabrics for kantha work are soft handloom cotton, tussar and silk.

Q. Your mother has been instrumental in reviving this traditional craft. Tell us how she inspired and guided you in your journey.

A. My mother Smt Sreelata Sarkar got admitted to the two years’ certificate course for women, Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan in the early fifties. She also had a personal association with Pratima Debi. Her daughter Nandini was a close friend of my mother.

She was blessed to have Nani Gopal Ghosh, Gouri Debi, Jamuna Debi among many others as her teachers. My mother always tried to create with whatever fabric available. She loved embroidering and tailoring. I grew up in Santiniketan. Children were not so preoccupied with toys or gadgets then. We enjoyed a lot of free space. I was very curious about her work and tried to create something of my own, following her footsteps. When I was in class eight, she made a free-hand drawing of a few motifs on an old piece of silk and instructed me to make a Kantha . That was my first association with this craft. My journey began there. She always made different kinds of hand embroidered items to use as gifts instead of buying at a shop. Just before I completed my school my parents had to shift to Purulia. After school I got admission into the department of Comparative Literature in Jadavpur University in 1972 and stayed in the hostel. For a while I lost all association with handicrafts and embroideries. In 1976 my parents shifted to Kolkata and during this period my mother decided to utilise her creative skill professionally and make saleable products. I continued my studies and also tried to support her with my limited capacity. Gradually she was able to inspire some of our neighbours to join her in kantha stitching. Slowly an interest in the art grew among the women as well as buyers. The process of making Kantha was quite accommodative for the women as they could work in between their daily household chores.

In 1978 my parents had to shift to Ahmedabad and this period saw a dip in my Mother’s kantha-making for some time. My parents returned to Kolkata in 1980 and my mother organized some women and started working again to fulfil her dream of creating kanthas and selling them to appreciative buyers. She went about it with great enthusiasm and soon had around 150 women to work with her. She worked so confidently and casually that none of us realized how much of hard work was going into the whole process! I was in fact, too preoccupied with my home, children and films (I had started working as a costume designer) to notice. Though I always appreciated and loved her work I could not do much to support her.

Kantha is an open canvas where you can depict whatever visuals fascinate you. But instead of choosing and interpreting at random, you have to consciously maintain an artistic harmony.

My Mother held her first exhibition at the Information Centre, Kolkata, in 1988. It was a unique event which drew a lot of people who were awed by the concept — a common and traditional rural art form depicted on shawls, sarees and other garments! I decided to join her in 1990 and tried to give her basic support by using my resources to connect with people and helping to sell her products. When I started working with her, I was amazed to see that kantha had become an integral part of her very existence. In retrospect, I never realized when exactly her passion seeped into my soul, inspiring me and sustaining my enthusiasm with memories of her boundless energy, her exceptional skill and vision. When the demand for kanthas started growing, she trained two boys to draw her designs on the fabric. Before that she used to take a pencil and go free-hand on any piece of cloth. A visitor would always be greeted with the familiar sight of her slight figure stooping over a spread-out cloth, drawing birds, a dandy with an umbrella, a woman cutting fish, a palanquin or a horse. Working with her was an extraordinary experience for me. I was fascinated and inspired by her creativity and the casual way she breathed life into each of her masterpieces. After she passed away in 1998 I felt an impulse to close the Kantha unit. But later I realized that I had a commitment to her and her work and started working again. I must confess that I have nowhere near her artistic capabilities and cannot hold a candle to her, but I strive to interpret her concepts with my own vision of this art form.

Q. Do you think Kantha has been explored to its full potential in modern and contemporary designing? Is there room for improvement? In what ways?

A. There are different kinds of Kantha embroidered products in the market. There is a moderately priced version of kantha-stitched materials with limited designs and colours. These are more popular because of the pricing and easy availability. There is another kind where the basic material is expensive, designs are more modern and the colours used are bolder.

For me, the best ones are those that have innovative concepts, are artistic in their finish and have creative colour combinations. Smooth and flawless embroidery sets off each of the kantha-stitched items, and since each is handmade each is unique and cannot be duplicated.

I believe that no creative art work can be explored and exploited to its full potential. There is always room for betterment.

You can always adapt and innovate tribal and folk designs from different parts of the world. For me Kantha is an open canvas where you can depict whatever visuals fascinate you. But instead of choosing and interpreting at random, you have to consciously maintain an artistic harmony. In this there can always be growth and improvement. You have to keep the eyes of your mind open to new ideas. You can draw your inspiration from anything….a mosaic tile, a coloured glass temple, forests in Europe during fall, human figures and so on.

Q. Does Kantha exist outside Bengal?

A. Yes, it does. Basically different kinds of quilts are made in different areas, from the simplest utility quilts to the most elaborate Indo-Portuguese coverlets. There’s the The Sujni of Baruch from Gujarat, the quilted palampores called Ledra from Jharkhand, the Sujni with figurative designs from Bihar, Koudi from Karnataka, Gudri from Rajasthan, the Laisingfee from Assam, Tripura and Manipur. The Rezai popular in Uttar Pradesh is also found in Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, North India, Bangladesh and Nepal. I’m sure there are more regions in India that has their particular style of quilts.

Q. Kantha is quite an expensive craft to be bought. How much of that actually trickles down to the craftswomen? Are they adequately rewarded?

A. The monetary value of a handcrafted product is relative. We don’t question the high prices of Kashmiri or Rajasthani hand embroideries because we have already accepted them. As I mentioned earlier, Kantha is of different categories and the price of each piece varies depending upon its quality and the labour behind it.

We have a deep-rooted misconception in our mind about art and folk art, and sometimes fail to notice that they are actually related. There are many folk artists who have established themselves successfully in the mainstream. Nowadays Kanthas are made in two different ways.

There are women who independently make Kanthas after their own designs and sell them. Then there are designers who conceptualise their designs, select their fabric, decide on the colour combinations and try to create a piece of art. The craft women’s contribution is their skill at embroidering. The question of ‘adequate reward’ is again relative in this context. It depends on the sale value as well as an individual designer’s discretion.

As far as my work is concerned, I always try to involve my craftspeople by sharing my thoughts and visions with them and try my best to give them what they deserve as payment for their efforts. I can humbly admit that I have not come up against any dissatisfaction in this regard till date.