It doesn’t require much fact-finding or “truth-seeking” to locate the illustrious author Saradindu Bandyopadhyay’s (1899 – 1970) massive body of work — short stories, novels, historical novels, at the forefront of which is the popular detective figure aka Satyanweshi Byomkesh Bakshi, alongside other characters like Boroda. Of late, Bandyopadhyay’s Byomkesh Bakshi stories (written in Bengali) have been reinvented both by mainstream Bengali cinema as well as by Bollywood, although following Satyajit Ray’s adaptation of “Chiriyakhana” (published in 1953) in 1967, Byomkesh Bakshi reappeared on screen as late as 1974 with Manju Dey’s directorial venture Sojarur Kanta (originally published in 1967).

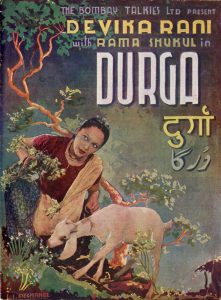

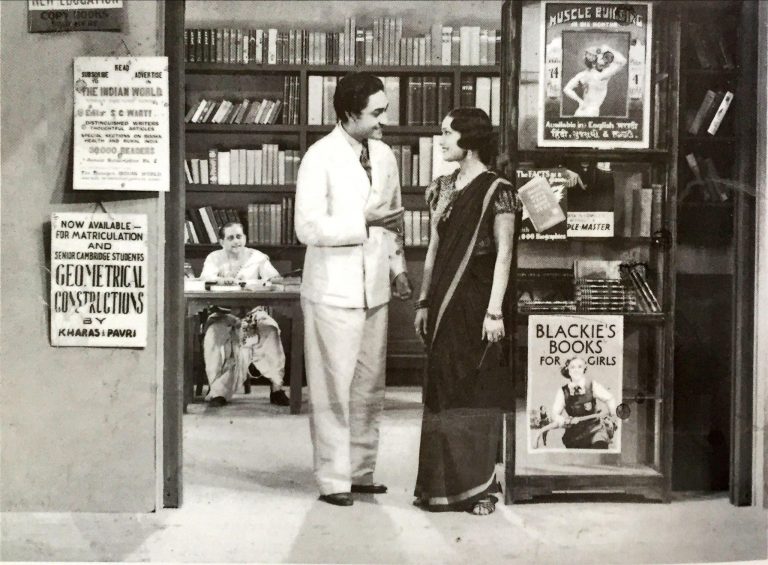

Yet, even if not unknown, it is virtually forgotten, or is shrouded in enigma like the history of early Indian cinema, that Bandyopadhyay had a distinguished career in films, as a writer, during the 1930s. Bandyopadhyay, credited as “Saradindu Banerjee”, wrote screenplays of a series of 1930s Bombay Talkies hits, and worked in collaboration with dialogue writers such as J S Casshyap (for Navjeevan, 1939), as well as writers like Gajendra Kumar Mitra (author and publisher), Sashadhar Mukherjee (producer with Bombay Talkies, Filmistan, and proprietor Filmalaya, Mumbai), and Narottam Vyas (for Kangan, 1939). Between 1938 and 1940, Bandyopadhyay wrote the story and screenplays of as many as six Bombay Talkies productions, including: Bhabi (1938), Navjeevan, Kangan, Durga (1939) – all of which were directed by the German maverick Franz Osten, as well as screenplays of Punar Milan (dir. Najam Naqvi, 1940) and Azad (dir. N R Acharya, 1940).

For an avid and average Bengali detective fiction reader Bandyopadhyay’s Hindi film career, particularly the stories of the popular Hindi Socials, may appear a bit startling. For instance, Navjeevan is a musical fantasy, in which the protagonist Mahendra, who belongs to a clan of warriors, is actually a hypochondriac. This becomes a problem as he tries to woo Menaka (the heroine) – who is obsessed with swash-buckling heroics. Mahendra eventually overcomes his condition by taking a magic pill, and by imagining that he has in fact has turned into a ‘hero’. Likewise, Kangan is a love story between Radha (Leela Chitnis) and Kamal (Ashok Kumar), the son of the village zamindar who wants to be a writer.

As Kamal goes to the city and becomes a noted writer, the zamindar and his men persecute Radha. In due course, Radha fakes a suicide, and finally goes away to the city to meet her lover. Furthermore, Bhabi, based on Bandyopadhyay’s “Bisher Dhuan” is the story of a conscientious young man, Kishore, who promises his dying friend that he shall look after the latter’s wife, Bimala. As Kishore brings Bimala home, trouble begins to brew. Meanwhile, Renu (the heroine), and her family, move in next door. Even as Kishore and Renu fall in love, societal taboos cast a long shadow on their relationship.

In order to examine the formations of such narrative tropes, one may suggest that, cinema was (and is) located within the mesh of various other cultural forms and media ecologies – inclusive of, but not limited to, literature, dance, music, theatre, gramophone, print, and a host of other consumer products[1]. Also, Hindi melodramas were borrowing heavily from the pool of writings in Urdu, Hindi, Gujarati, Marathi and Bengali, and the circuits of cine-workers were/are dynamic and ever evolving[2]. Moreover, during this period, a number of well-known playwrights and authors worked both as writers of films and as directors (for example, Premankur Atorthy, Sisir Bhadhuri, Kazi Nazul Islam, Sailajananda Mukhopadhyay, Premendra Mitra et al), in the film industry based in Kolkata and elsewhere[3], to introduce complex storytelling to the cinematic form, inculcate ‘respectability’ and wide-spread acceptability in literary modes[4].

Bandyopadhyay, for instance, was born in Bihar, and had studied at Vidyasagar College, Kolkata, wherein the eminent playwright and thespian Sisir Bhaduri was a teacher. As per rumour, Bandyopadhyay – who had also studied law — was invited by Himanshu Rai (proprietor Bombay Talkies), after Bombay Talkies’ principal writer Niranjan Pal parted ways with them[5]. Any which way, by then, Bandyopadhyay had already published some of his pathbreaking works, including about ten Byomkesh Bakshi stories.

Bandyopadhyay, credited as “Saradindu Banerjee”, wrote screenplays of a series of 1930s Bombay Talkies hits, and worked in collaboration with dialogue writers such as J S Casshyap

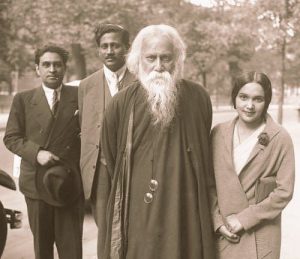

However, Bandyopadhyay was not the only author who was involved in such collaborative ventures and imaginings. For example, Niranjan Pal, who was the son of the nationalist leader Bipin Chandra Pal, and had participated in a terrorist action in Kolkata, was quite a celebrated writer / director in the Bhadralok circles. He was sent off to Marseilles and to London where he acquired writing and filmmaking skills, and thereafter, teamed up as scenarist on all Himanshu Rai’s silent productions. Likewise, Charu Roy, who was a Bengali painter, had studied at the Presidency College, and had worked on the first Bengali film journal, Bioscope (1930), and later edited the Rangmahal journal. Eventually, Roy became a set designer for Sisir Bhaduri’s landmark film Seeta (1933), and functioned as an art director for Himanshu Rai as well as for Modhu Bose’s productions.

Rai himself had spent substantial time at Santiniketan, and had studied law in England, where he met both Pal and Devika Rani, the doyenne of Indian cinema. Devika Rani was related to the Tagore family both through her paternal as well as her maternal line. Bandyopadhyay’s collaboration with Bombay Talkies and his stay in Bombay/Mumbai until 1952, therefore, informs us about the many possible liaisons which were being built, and were generating some of the pioneering films of Hindi cinema[6]. Such networks also alert us about the ways in which exceptional authors like Sadaat Hasan Manto and many others, arrived at Bombay during 1930s and 1940s, and joined forces with the film industry. “Saradindu Banerjee’s” role in that regard was remarkable.

Image courtesy: IMDB, Wikimedia Commons, Bressonian, Pinterest

Notes:

- Also see Madhuja Mukherjee, “Of Bhadramohila, Blouses, and ‘Bustofine’: Re-viewing Bengali High Culture (1930s-40s) from a Low Angle”, Popular and Visual Culture: Design, Circulation and Consumption, ed. Clara Sarmento and Ricardo Campos, Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Cambridge (2014): 145-166.

See Kuashik Bhaumik, “The Emergence of the Bombay Film Industry 1913–1936.” Unpublished Ph.D thesis, University of Oxford, 2001; Debashree. Mukherjee, Bombay Hustle, Making Movies in a Colonial City, NY: Columbia University Press, 2020, and Monika Mehta, Madhuja Mukherjee, ed. Industrial Networks and Cinemas of India: Shooting Stars, Shifting Geographies and Multiplying Media, London/ NY: Routledge, 2021.

See Madhuja Mukherjee, New Theatres Ltd., The Emblem of Art, The Picture of Success, Pune: National Film Archive of India, Pune, 2009.

- See Madhuja Mukherjee “Rethinking popular cinema in Bengal (1930s–1950s): Of literariness, comic mode, mythological and other avatars”, South Asian History and Culture, 8.2 (2017): 122-142.

- See: http://thebigindianpicture.com/2013/10/birth-of-an-industry/

- Also see Madhuja Mukherjee “Forking Paths of Indian Cinema: Revisiting Hindi films through regional networks”, The Routledge Companion to World Cinema, ed. Rob Stone, Paul Cooke, Stephanie Dennison and Alex Marlow-Mann. London/ New York: Routledge (2018): 213- 224.