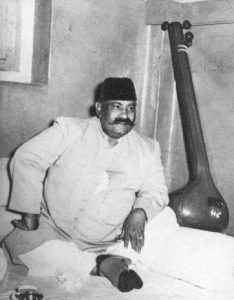

In a late night scene in K Asif’s ‘Mughal e Azam’, a lovesick Prince Salim romances Anarkali the court dancer surrounded by fake flowers. Behind them is a somewhat crude hand painted replication of the erstwhile Mughal royal residence the Fatehpur Sikri. In an age of green screen animation the scene might seem amateur and perhaps even laughable but for the magical background score. While a dramatic Dilip Kumar romances Madhubala, a lonesome voice transports us to a dream called raag sohini. Tansen, the court singer of Emperor Akbar sings ‘Prem Jogan Banke’ in the wee hours of that enchanting night. The song is so subtle yet so overpowering and the singer touches each note with such clarity and ease that you’d want to close your eyes and shut the lovebirds out. The melancholic romance of the music entangles you like a serpent and you don’t want to be rescued. That voice belongs to Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan – the genius frequently referred to as the Tansen of 20th century.

Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan was born exactly 120 years ago in Kasur (now in Pakistan) on 2nd April 1902. His father Ali Baksh and uncle Kale Khan were artists of the ancient Patiala gharana (somewhat looked down upon by the maestros of Jaipur and Kirana gharanas). Father Ali Baksh played the dilruba and was widely known among the music fraternity for his ability to copy and caricature eminent singers. Ali Baksh’s brother Kale Khan was a vocalist known for his heavy yet sweet voice. Bade Ghulam Ali Khan trained with Kale Khan from five to twelve years of age.

As a teenager, he once performed in front of his father Ali Bakhsh. However, after his recital ended Ali Bakhsh left without a word. Later Bade Ghulam asked his father’s opinion on his performance over dinner. Ali Bakhsh said, “What should I tell someone who is out of tune about the quality of his song?” Bade Ghulam stopped eating and left his seat. He was determined to show his father that he could master the fineries of tune.

After being chastised by his father, Bade Ghulam Ali poured his soul into rigorous rewaaj. He practiced into the wee hours of the night. So as not to disturb his neighbours with his rewaaj, he went to the nearest cremation ground. It was perhaps around this time that he refined the qanun and created the swaramandal. It was easier to carry compared to the heavy tanpura and it also helped him practice in different scales. He spent much of this time practicing the palta rewaaj which in his later years helped him move so effortlessly from Bhupali to sargam in Malkosh or Durga raga. When he returned home every morning from his rewaaj sessions, his relatives would lament on his carefree attitude and his lack of interest to earn a living. Shortly afterwards Ali Baksh remarried and Ghulam Ali picked up the sarangi to run his family. There’s no evidence of his receiving any formal training thereafter. He was about twenty years old at this time. He started accompanying a tawayef called Gigbaai on the sarangi.

In those days, Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan of Kirana gharana was quite famous in Lahore. Bade Ghulam was a fan. At a concert he offered rupees twenty five to the Ustad as nazrana and expressed his wish to become his shaagird (disciple). But the Ustad was quite a snob. He asked his other shaagird to give some basic palta taan and meerkhand to Bade Ghulam Ali but refused to give his gayaki to him.

Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan never stopped practicing his rewaaj. Not even at the peak of his career. It is said, Faiyaz Khan never did the rewaaj after forty. Ustad Amir Khan was hardly ever seen to rewaaj. But Bade Ghulam Ali was always with his swarmandal practicing the various tunes. His voice production, use of tone and the way he touched his notes were marked by his remarkably relaxed stance. This is evident in how hardly any of his body parts save his lips were seen moving even when he was performing at taar saptak. In his book ‘Kudrat rang Birangi’ Kumar Prasad Mukherjee stresses, it is because of his relaxed stance that Bade Ghulam could touch the notes he intended to with such practiced ease. Though he amalgamated the styles of Patiala gharana Gwalior gharana and Dhrupad in his gayki, it was his training with Kale Khan that had ingrained in him the techniques of manipulating volume, touching notes and modulating voice. It is also one of the reasons why he achieved unparalleled grace as a master of thumri. In fact he could render soulful ghazals, erotic thumris and skillful khayals with equal ease. We get a glimpse of his rewaaj in the documentary produced by Sangeet Natak Academy.

After the partition of India, the Ustad returned to his birthplace Kasur. But surprising as it may sound these days, this Pakistani artist was offered citizenship of India in 1957. He was also awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1962. His remains are buried in Daira Mir Momin in the old city of Hyderabad where he breathed his last on 25th April, 1968. The sweet and forlorn voice of Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan has sheltered many lost souls in the sub-continent. His legacy lives on on both sides of the border and hopelessly connects two nations bent on severing their rich cultural ties.

Reference:

- Kumar Prasad Mukherjee, ‘Kudrat Rang Birangi’, Ananda Publishers

- ITC Sangeet Research Academy