Uma Dasgupta is a renowned scholar and biographer of Rabindranath Tagore. In this essay she discusses at length the social and economic reforms undertaken and implemented by the Tagore family in the tribal villages around Santiniketan. Originally written as a paper to be read out at a seminar in the University of Illinois, this essay will be published in four parts on Space.ink. This is the fourth and last part.

Visva-Bharati was registered as a formal institution in 1921

and with it was formalized the new School of Agriculture founded at

village Surul two miles from Santiniketan where Tagore had bought land

for a farm in 1912 to begin the work which later became Santiniketan’s

twin endeavour, Sriniketan. The teachers from Santiniketan used to

do some farming on that land to educate their pupils and to mingle with

the villagers by taking turns to live there. But they could not sustain

the effort as the place was so full of malaria. A new beginning awaited

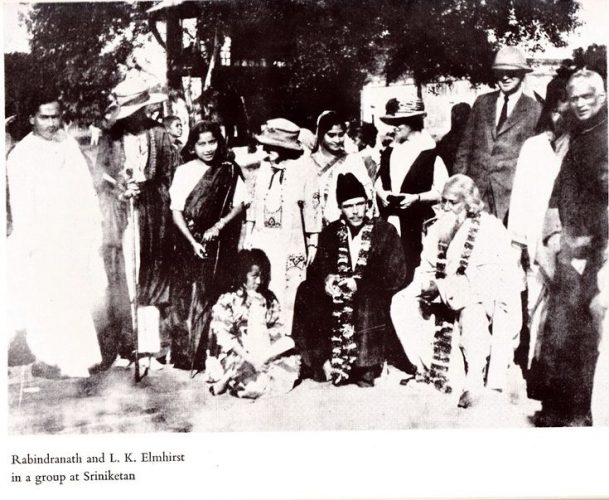

till Leonard Elmhirst came whom Tagore met in America in 1920.

Elmhirst was an agricultural scientist from England trained in Cornell. Tagore had been previously told about Elmhirst as an idealistic young man of agriculture who was interested India. Tagore said to Elmhirst when they met,

I have established an educational enterprise in India which is almost wholly academic. It is situated well out in the countryside of West Bengal at Santiniketan. We are surrounded by villages, Hindu, Muslim, Santali. Except that we employ a number of these village folk for various menial tasks in my school, we have no intimate contact with them at all inside their own communities. For some reason these villages appear to be in a state of steady decline. In fact they are all in decay. Some years ago I bought from the Sinha family a farm just outside the village of Surul, a little over a mile from my school. I hear that you might be interested in going to live and work on such a farm in order to find out more clearly the causes of this decay.

In this work Elmhirst was joined by Rathi and others. It is important to

note here that of the first four Executive Committee members of the new

School of Agriculture two were University of Illinois-trained, Rathi and

Santosh. Besides them were Leonard Elmhirst and a teacher from

Santiniketan, Gour Gopal Ghosh, with Tagore as Chancellor. This work

was broadened to become an Institute of Rural Reconstruction and called

Sriniketan, the twin of Santiniketan.

It has to be said in all fairness to both the Tagores that although

Rathi did his best for the next twenty five years in taking charge of his

father’s cherished scheme of rural reform through the Sriniketan

experiment, their inspirations for this work were not the same, Rathi’s

and his father’s. For Tagore, as we have noted earlier, it was a spiritual

experience that brought him close to the common man.

Rathi responded in a more businesslike way to the work in the course of time. In the 1930s there was a change in the ideals of the Sriniketan experiment. Rathi decided on a goal of harnessing Sriniketan’s capability as an institution by making it financially viable, even profit-generating.

To Rathi who also felt compassion for the poor and helpless people of his country it did not go as far as that. Father and son both struggled for the work – each in their own ways – and father could do as much because his son struggled with him. But the burden of doing something so entirely against the current of the times took its toll particularly on Rathi because he had no escape route to poetry as his father did. In 1924 Rathi wrote to Mayce Seymour describing his pressures as follows:

At Santiniketan I am entirely at the mercy of my office – and the work has been so engrossing that it left no leisure for the ordinary amenities of life … this work has so taken hold of my whole being – that I cannot rest until the organisation is complete and the ideas has been given a concrete form. There is a real pleasure in this and it compensates for all the sacrifices I have to make. You will be glad to hear that the country is at last responding to our appeal. So long it had been a constant struggle. The mind of the people had been entirely captured by the politicians, they had been kept hypnotized by the hope of short-cuts to freedom. But it is only recently they are coming to realize the importance of constructive work and building from the bottom up. The ideal of the Visva-Bharati is coming to be more and more recognized.

Understandably, therefore, Rathi responded in a more businesslike way to the work in the course of time. In the 1930s there was a change in the

ideals of the Sriniketan experiment. Rathi decided on a goal of harnessing

Sriniketan’s capability as an institution by making it financially viable,

even profit-generating. This was done mainly through marketing

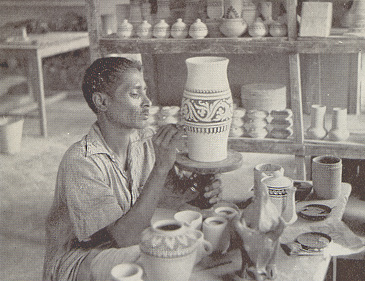

Sriniketan’s artistic products. Earlier, manufacturing artistic products was

a part of Sriniketan’s ideology of making the villagers self-supporting mainly through engaging them in cooperative work.

Our salvation lies in thus making our villages self-reliant and knit together by the ties of corporate life.

But in the 1930s the emphasis on making the villages self-reliant was

undermined. Although the original work continued to some extent — that

of scientific experimentation along with the comprehensive approach of

intensively working for the all –rounded development of a village — it

was no longer as important after Sriniketan’s re-organisation. The

‘reorganization’ Rathi attempted in 1934 and 1938 emphasized the

importance of restructuring Sriniketan ‘as a business’.

The farm, the dairy and the poultry lost their justification merely as experimental units which is how the Sriniketan work was designed to spread to the surrounding villages. It was proposed to lease the farm and the dairy to external agencies retaining only a two-acre experimental plot and one or two stud bulls for use in the villages. Even the parties were selected in 1936 but for reasons not entirely known was not followed up. It is known from the correspondence that Elmhirst was not happy with the decline in research and experimentation. We find Rathi explaining to Elmhirst in a letter of 1938,

Sriniketan is no longer in the position that it was then when it was neither sure of its mission nor of its material support. Now we know better the nature of the real problems before us and feel more confident of our success in tackling them. The time has come to correlate our experiences and work out the methodology of rural reconstruction and devise broader schemes of rural health, rural education, and such vital problems affecting the rural population in conformity with the needs of the country. With the public administration getting more and more autonomous and democratic there is greater interest and keener demand for carefully worked out schemes of public welfare. Sriniketan can no longer remain wholly satisfied with meeting the needs of the local rural community – it must begin to think in terms of a wider field.

In this new phase of Sriniketan’s reorganization the Weavers and Leather Workers Cooperatives continued to do their work as de facto employees of the institution rather than as men and women who were being assisted to organize themselves and become self-supporting. Their new significance to the institution was as manufacturers of marketable artistic crafts. Whether the weavers could thus regain their old footing and whether the cooperative of shoemakers would become self-sufficient— such issues became secondary in the late 30s. In fact tanning which was started at the inception of the institution was abandoned. That too was replaced by artistic leather craft. Basically this was a change which emphasized artistry in design combining Indian and foreign motifs, what in today’s language could be seen as a move towards ‘ethnic fashions’.

Rathi and his wife Pratima were pioneers in an important transformation in urbane Bengali taste and this trend spread elsewhere in India. The Sriniketan-Santiniketan style came to be recognized by the cultured social milieu. “Sriniketan goods” began to claim markets all over the country. The older ideals of research and experimentation as the basis of rural reconstruction, of an exchange between traditional wisdom and scientific knowledge so dear to Tagore’s dream, were weakened. Tagore clearly understood this when he wrote in a letter of 1939 to a new recruit to Sriniketan,

I can no longer work myself. I see imperfection before me; if people like you now stand by me with new vision and new strength my exhausted self would feel confident again.

With everything said the fact remains that Rathi undertook a near impossible task which was not of his making. He did it with loyalty and conviction because he respected and loved his father’s inspiration, also because he recognised the need to help. This was not just true of the Sriniketan experimentation but it so happened that in the 1930s he had to take charge of the whole of Visva-Bharati.

As is the common human experience, individually-spurred institutions find it difficult to get many people whom they can trust with the same principles and ideas. By his own admission Rathi had little time left for Sriniketan given his responsibilities for the whole of Visva-Bharati. There were other dedicated workers at Sriniketan but it seemed there were none who could take the whole task on their shoulders and steer it through with singularity of purpose.

Moreover the team of pioneers were not necessarily united over methods and approaches. Some were even skeptical of the scientific approach or for many the ideas were too new-fangled. But they had good personal rapport with the villagers and were therefore indispensable in the village work. Rathi once wrote a detailed letter to Elmhirst with his assessment and experience of each of his colleagues in the Sriniketan work showing their differences and complexities.

For Tagore these things hardly mattered. To him the rural work was his ‘initiation’ into ‘the religion of man’, hence not to be seen only in terms of success or failure. What was this initiation? We have it in his words, again and again,

The picture of the helpless village which I watched one day as I sailed past on the river remained with me and so I have to make the great initiation here.

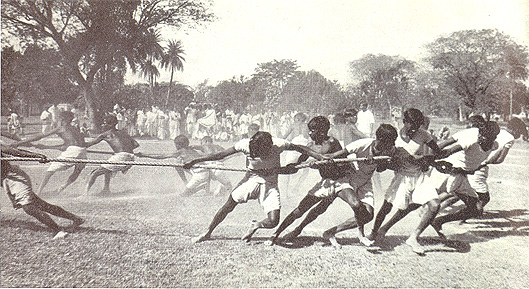

It is also useful to keep in mind that Tagore had deliberately created an institution where policies could not really be handed down and pursued over long periods of time. In his institution there were no mandatory reports, no clear directions, no rigid requirements and no red tape. Both at the top and at the bottom much depended on what the individual made of the job. Some directly beneficial results were certainly obtained from the Sriniketan work: those were evident in the reduced rate of deaths through the health work in the villages, in involving a larger number of villagers in the industries programme, and in the introduction of rotation crops as a practice. Deaths from malaria were down by 27% between 1928 and 1948. Among the long-term positive results for our large and then totally underdeveloped agricultural country was that the independent Government of India adopted Sriniketan’s principles widely through its Block Development Scheme and Community Project for the villages.

In another sphere, and this was also on a national scale, cottage industries became a major movement of the Government in giving work to our large but dying body of traditional craftsmen after the expansion of Sriniketan’s crafts activity. But the larger picture of the village was hardly changed.

Tagore got something of what he wanted most of all from the Sriniketan effort—a relationship with the village. A beginning was made to understand its problems. To him it was not enough to simply know that the villager spun one and half pound of yarn instead of one pound, or that he now got from the land a maund and half of paddy instead of one maund. He told the workers at Sriniketan,

I want much more than that, I want a complete awakening of his [the villager’s] whole mind.

But for Rathi, as a younger man of ideas, with a sense of business to sustain the effort, he could easily have argued that one approach did not have to exclude the other. Rathi could also argue given a chance that short of giving his life to the work of scientific agriculture and rural reform to the exclusion of all else there was not much more he could have done to attain his father’s dream. Despite its honest high ideals for social justice the work at Santiniketan and Sriniketan was personality-driven. It did not take root in society. Even the villagers had their own sense of reality and Rathi was aware of that. He wrote how once an old villager with a flowing white beard had said to him,

Babuji, what is the use of all this talk? I don’t think our young men will do anything with all this rubbishy reforms they glibly expound to us. Give us a Lenin and everything will be changed.

The spell was broken. I got up and hurried back to my boat – wrote Rathi.

At most what could have been idealistically and practically sustained is the experiment of scientific agriculture and rural reform on the lines laid down — even if on a small scale — without stopping. That did not quite happen. Over and above, there were larger risks that came on the scene. Private donations began to dry up in Tagore’s last years followed by his death. The staff were becoming insecure and restless. The whole institution might have gone into oblivion had it not been endowed with Government of India’s support in 1951, ten years after Tagore’s death, with turning Visva-Bharati into an university under the University Grants Commission.

There again Rathi took the leadership in seeking the government’s intervention. Expectedly that has created other problems by way of bringing the institution in line with other run of the mill universities in the country. Government of India themselves get concerned from time to time over Visva-Bharati veering away from Tagore’s ideals. But even that is a valuable point of reference in the history of an institution, a reference to its foundations as an experiment for a distinctive ‘way of life’. Today the twin institutions of Santiniketan and Sriniketan continue to be a reminder of that early history to those who stop to think or to ask.

This discussion should not be closed without noting that the University of Illinois has played an integral role in Visva-Bharati’s history of pioneering scientific experimentation in agriculture as part of Tagore’s ideas and actions for a distinctive ‘way of life’ that was built upon an education combining the city and the village. Tagore sent three of his young men to this university for that education. Also, on an emotional level, the experience of this university brought happiness and affection to the lives of both father and son. The letters Tagore wrote and received from Urbana and the letters Rathi wrote throughout his life to his friends and mentors at Urbana bear witness to this landmark encounter. In his first letter from Urbana in 1912 Tagore wrote to William Rothenstein in England,

Most of the professors here are genuinely fond of Rathi and they are glad to have him back among them. That is the chief consideration for us to choose this place. This is a quiet place—has all the advantages of a village and the conveniences of a town. The country around is flat and open, which has a great attraction for me, reminding me of our own scenery. It has no pronounced features in the shape of hills and valleys and for that very reason it seems to me so full of repose—and the simplicity and obvious monotonousness of the physical aspects here have the effect of setting one’s mind free.

There were not many universities anywhere in the world where they nurtured a ‘Tagore Circle’ and gathered to read his poetry on his birthday from year to year. There are archived letters signed by the members of that Tagore Circle which met at the Cosmopolitan Club of this University on 6 May each year from 1913 to 1925. Arthur Seymour wrote to Tagore on 9 April 1913,

Our little Tagore circle is enthusiastically reading the ms.copies which were so kindly sent us and though we are not many at present we hope to create a wider interest and a greater appreciation in others.

That generous spirit continues to this day in the university’s response to the idea of remembering Rathi after a hundred years of his association with the University and with the Cosmopolitan Club he helped to establish. I feel honoured to be a part of this remembering and of this university’s Tagore Festival which has sustained this effort for eighteen years. I wish it long life.