The Silent Footsteps

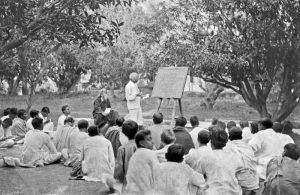

His footsteps were completely silent. None could ever predict when he would arrive in the room. Let’s imagine, you were painting – sitting cross-legged on the floor – engrossed in the fluidity of your brush creating waves on the paper. Suddenly, you felt someone gently touch you on your shoulder. Between 1901 and 1941, you shouldn’t have startled – had you lived in Santiniketan, Tagore’s university. Because, you would have known it was Tagore. he has been standing behind you, watching you paint. For how long? You couldn’t have guessed.

The gentle touch had already reassured you. Now, you turn your head to find a tall bearded man with a generous smile standing behind you, looking into your eyes. You meet his glance and look back into a pair of eyes glowing with white fire.

Was the fire in his eyes real? Or an illusion? Created by awe?

You couldn’t have been sure. But you could see it. Albert Einstein saw it. So did the widow of the Soviet Film director Sergei Eisenstein. It was true for all the students learning in the university, Bisva Bharati.

On the basis of this simple description of Rabindranath Tagore, we can find two elements – almost contrasting – in his character –

- Non-imposing, reassuring, affectionate ( The Silence footsteps )

- A secret fire burning in his heart (The glowing eyes ).

These two elements had driven Tagore to two opposite directions.

The first element created in him the poet, singer, and finally the lyricist and composer of nearly 2,500 immortal songs including dance dramas. (It must be confessed 2,500 is an astronomical figure for someone composing original songs.)

While composing songs and poems, Tagore was soft and enduring and non-imposing. Let me give you a simple instance to illustrate how un-complaining he could be – even when writing highly political songs. (It’s globally accepted that the special genre of music needs intense anger and a mood to assault – Beethoven’s Turkish March, for instance.)

But what Tagore did was diametrically opposite. In order to understand this, we have to go back in time to the year 1905. Lord Curzon, the then Viceroy of India, proclaimed that Bengal would be divided into two provinces as it was too big to be governed properly. However, the viceroy was arrogantly reluctant to explain his concept of ‘Proper Governance’.

A considerably large part of the people – ordinary as well as the intelligentsia – voiced their dissent against the division of Bengal. But, the likes of Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Dadabhai Naoroji could not convince the members of the Viceroy’s council to change their mind. Largely because the British parliament headed by one Arthur James Balfour (a conservative with a ‘Kipling moustache’), was also involved in the mêlée.

Arthur Balfour, a well-informed prime minister and an author of interesting books like ‘The Foundation of Belief’ and ‘Theism and Humanism’, worked under the monarchy of Edward the seventh. Therefore the G.O. (government order) proclaiming the partition of Bengal had already been signed by three men – Curzon, Balfour and Edward the Seventh – who were highly dissimilar in character. The names, justifiably cast aside by today’s India, become relevant all at once to understand the complexity of the curse. Congress found the G.O. impenetrable as it was a three tier decree. The British government had a special talent for creating ‘Three Tier’ administrative structures to make everything look unchangeable.

It was at this juncture that Rabindranath Tagore entered the scene.

What he did was unparalleled in history. He didn’t write any letters to the prime minister of England. On the contrary, he wrote only 26 short and simple songs summoning the people of the East and West of Bengal to remain united.

Now how were the songs? Did those express an uncontrollable anger? Were those war-calls? Marching songs?

No, they weren’t. He did not use words like ‘British’, ‘Guns’, ‘Firing’, or ‘Blood’ in those songs. Not even words like ‘Imperialism’ or ‘Freedom’. In spite of that, the songs could vibrantly inspire all of Bengal to remain united.

On the morning of 5th October, 1905, the people of Calcutta witnessed some sort of a miracle. Tagore, the poet, was leading a procession of hundreds of people. He was singing his new songs in his celebrated tenor. His followers kept surging like a roaring sea behind him. What started out with a few hundred people became a one hundred thousand strong crowd, according to the memoirs of the witnesses.

Even the British Police force did not try to stop the demonstration. It is said, that even a number of officials representing the Calcutta Police on road were hypnotized by the magic of Tagore-compositions. Sir Frederick Halliday, the then Commissioner of Calcutta Police, could not punish the members of the force as no clause in the Code of Conduct had anything against anti-British literature.

But how were the songs? Let me give you an example –

“My Bengal of gold,

I love you.

Forever your skies,

Your air set my heart in tune

As if it were a flute.

In spring, O mother mine,

The fragrance from your mango groves

Makes me wild with joy,

Ah, what a thrill!

In autumn, O mother of mine,

In the full blossomed paddy fields

I have seen spread all over sweet smiles..”

What’s most remarkable is that The British Government was never ever mentioned in the song. Even while protesting against a world-conquering Empire, Tagore did not try to make his followers blood-thirsty. Instead, the poet reminded them of nature’s bounty in the land of Bengal. And by doing so, he completely ignored the British which in turn dramatically diminished the value of the British Power and British Merchandise to his followers.

Yet the purpose was served. The partition of Bengal was stalled. The British rulers were stunned to see the inexplicable ‘power’ of Tagore’s songs to inspire and unite. He was 53.

The Burning Eyes

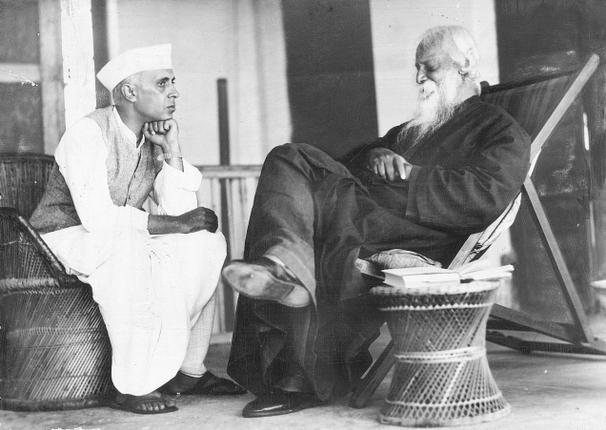

Now, let’s move forward in time and revisit Tagore when he is 70.

There he is at his writing desk. Several small bottles of writing ink are scattered on it. Oil Pastels, pencils, brushes and water colors are also seen strewn around.

Of these, the most valuable are the small bottles containing ‘Pelican ink mixed with spirit’. ‘Spirit’ is used to help the ink dry quickly when applied on paper. Quick drying is the first priority, because the man who works on the table is very impatient when he is painting a picture. He can’t wait for the colors to dry. That’s why he never created any oil-painting (except one which was left half-done) for the fear of waiting for several hours for the oil to dry.

Ironically, this is the same man – silent, non-imposing and an epitome of endurance – the poet and protester of 1905.

But, why has his calmness vanished? Why has he become so restless? Because, now he is busy painting. He is now an old man, yet extremely attractive and handsome and he is busy painting stooping over the table.

The white fire is still glowing in his eyes.

This fire, egged him on to create more than 2,500 paintings. Not all were ‘complete’ paintings in the conventional sense of the term. Some were just a few scratches of black ink on paper. These were done with the same fountain pen he used to write his poetry. Many ‘paintings’ were done using wooden color-pencils. The colors most preferred by him were colored-writing-inks and oil pastels. Now comes a pertinent question. Was Tagore trying to create something which could have been labeled as ‘Surrealistic’?

The ‘scientific’ answer which is still valid according to ‘simple and elementary psychology’ is this – Tagore wouldn’t have laughed with a combination of amazement, joy and a bit of embarrassment, had he ever tried to create ‘something’ faintly echoing Surrealism.

Was he not aware of the various Art Movements making storms in Europe in the first half of the 20th Century? Couldn’t he identify Picasso’s girl standing before a mirror? Or, Dali’s melting Clocks? Or Chagall’s violinist with a green face? Obviously yes, because Tagore was invited so often to Europe.

But, while creating his own paintings, Tagore became oblivious to all – from Van Gogh to Picasso. Not only did he forget the western painters, but also perhaps the 5000-year-tradition of Indian Art – from Indus Valley to the Bengal School. What Tagore created was entirely his own.

Tagore was an instinctive painter. He did not pre-plan any image before starting a painting. He just picked up a paper of any size and shape – even newspapers at times – for painting. Within a few seconds, his fountain pen started playing – mostly without any aim – on the paper. He loved creating dense crisscross with black ink resulting at times in an aimless pattern of light and shades.

He loved to create different kinds of textures. But, Tagore’s textures are not like those of Van Gogh’s. Van Gogh always created textures in high relief with the help of dense oil colors, while Tagore created textures with writing ink of various hues. The writing ink can’t create a relief the level of which is higher than the paper. Even if it does, it’s totally microscopic. This is one of the reasons why the textures created by Tagore were faster than that of Van Gogh.

The subjects of Tagore’s paintings were strange – diametrically opposite to his poems and songs. In his poems and songs, he was serene and able to create inexplicable beauty. Whereas in his paintings he was like flowing lava churning out from the volcano. It was a mystery indeed. How could the same man change his attitude towards art so fundamentally?

One might ask, was the change caused by the change of the medium? Can a medium be so powerful as to change man’s character from a gentle poet to a frenzied and aimless painter?

Therefore, does the medium of art create an artist’s nature? Or, vice-versa?

The question is philosophical. And, most probably, unanswerable.

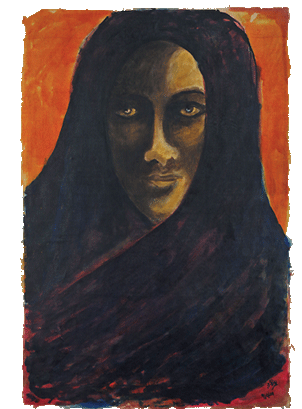

From the poet’s paintings, these are coming out like a series of waves – crying animal never seen, melancholy faces of women peeping out from a black veil which reminds you of Death, a face of a giant bird whose total body represents a mixture of a building and a dinosaur, The affectionate face and soft body of a beautiful woman is caged with unpredictable straight lines ….

Through his paintings, Tagore gives us a freedom from the Newtonian world of total predictability to the world of infinite probabilities of the new Quantum world. In short, Tagore’s paintings are the art of infinite probabilities, born out of an unplanned journey of a decade. Sorry, we have come to a serious note.

Let’s come back to a description of Tagore literally talking to a woman during creating her in a painting. You can feel his love for his paintings from what he is saying —-

“Why are you so somber? Do you want more colors? Haven’t you liked the green? Well, take the red. See, how long I am trying to win your heart; yet your eyes are tearful. Then, stay with your eyes filled with water… I love to see moist eyes …”

This whisper – secret and very personal – proves that Tagore painted from love, for love and with love.

2 Responses

Nice writeup.

Thanks for sharing.

Take care.

Beautifully researched, enriching read. You have drawn the contrasts between Tagore’s art and poetry so lucidly. Thanks a ton for such an enlightening article.