In a biographical essay “Amar Katha”[1] or “My Story,” popular Bengali actress Sabitri Chattopadhyay writes about her family’s impoverishment upon their displacement from Kamalapur in East Pakistan to Calcutta, India in 1947. She speaks of her struggle to put food on the table which led to her working as an “extra” in Bengali films and eventually, to a career in theater and film:

“We were going through very difficult times. My father didn’t have an income. We had to rent out one room of the small two-room house where we were living, and use the rent-money towards domestic expenses. But it didn’t do much. … So, to help my father run the household, I cast aside all inhibitions and lined up at the gates of the film studio day after day. There would be openings in crowd scenes or dance sequences. It wasn’t much money. And if I earned ten rupees, the agent would deduct five. Even so, it was something in a poor household. At such times I’d forget that we had once owned a palatial home in Kamalapur, near Dhaka. … Not only had we never experienced scarcity before coming to Calcutta, but we couldn’t even imagine it. From there to this sliver of a house, it was a nightmare. … Although my father was opposed to my acting with strangers, such was providence, that at a time of rising costs, it wasn’t possible to run the household on the rent from one small room. In the midst of the riots, the Partition, and his terrified escape, he couldn’t bring anything. In exchange for our huge home, that little house was all he received. So, I had to plunge into acting and be the economic stave for my penniless family.” (252-53; 258)

Many years later, Sabitri Chattopadhyay’s talent would be nationally recognized with a Padma Shri award.

That Chattopadhyay even contemplated acting in films and on the stage as a career is evidence of a conspicuous change in the mindset of Bengali Hindu society towards middle-class women’s wage labor outside the home. And the reason was the tumult generated by the riots surrounding the Partition. The economic collapse the refugees experienced resulting from looting, forced evacuations and the loss of landed property, combined with the deaths of male earning members in outbreaks of sectarian violence, could be partly salvaged through women’s salaried-work. Thus, many displaced middle-class women began to acquire an education and the skills for gainful employment, and looked for paid-work. (Although for educated upper- and middle-class Bengali women opportunities for professional employment, mostly in the fields of education and medicine, first opened up in the late-19th century, even in the early decades of the 20th century women job-applicants were few. But the Partition in 1947 changed that!)

Many educated refugee women favored teaching positions and they swiftly filled openings in girls’ schools in Calcutta. In his novel, Bidisha (1952)[2], Narayan Gangopadhyay notes the rise in demand for teaching jobs:

“Things were quite different seven or even five years ago. Finding a good teacher for a girls’ school used to be very difficult, and schools would compete over a single college graduate. But overnight the situation has changed entirely. Partition! The uprooted people from East Bengal have flooded into Calcutta, and the struggle to survive is unrelenting. Nowadays there’s no need to sweet-talk the BAs and the MAs to teach, instead they are themselves making the rounds at girls’ schools. Forty rupees, thirty rupees, even twenty-five rupees, they’ll accept anything. Whatever they can get – just the smallest stable foundation on the quicksands of uncertainty.” (26)

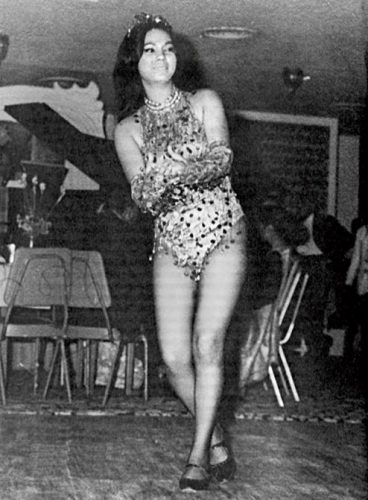

While teaching positions may have been preferred by displaced women, for those faced with the total collapse of their family’s wherewithal, they could not be choosers when it came to employment. For the first time, formerly homebound middle-class women worked as clerks, bank tellers, telephone operators, and as police; some found employment as cooks, nurses, nannies, and even maidservants. Others trained in the arts and crafts. The performing arts also benefited from the participation of displaced middle-class women. At the beginning of this essay, I mentioned Sabitri Chattopadhyay who built a career in theater and film. But she was not alone. One of the finest actresses of the Bengali stage and screen and the winner of the National Award for Best Actress in 1970 for her performance in the film Dibaratrir Kabya (The Poetry of Night and Day), Madhabi Mukherjee was also a Partition refugee. She and her family migrated from East Bengal to Calcutta, in the 1940s. Like Sabitri, Madhabi Mukherjee’s decision to act on stage was also driven by economic need. In an interview she said, “Our financial situation was such that I had to work. So I started acting in plays.”[3] She started her career in theater, as a child artiste. Her first film was released in 1950 when she was only eight years old. Like Sabitri Chattopadhyay and Madhabi Mukherjee, Bengali folk theater or jatra performers Jyotsna Datta and Bina Dasgupta, and prominent cabaret performer and film actress Arati Das (better known by her stage name, Miss Shefali), all endeavored to avert the economic crisis brought upon their families as a result of the Partition through successful careers in West Bengal’s entertainment industry.

Displaced women eager to acquire skills suited to different occupations received training from governmental and non-governmental bodies including the All India Women’s Conference, the All Bengal Women’s Union, the Nari Seva Sangha (Association for the Service of Women), and the Communist Party of India-affiliated Mahila Atmaraksha Samiti (Women’s Self Defense Society). The All India Women’s Conference not only provided instruction in different skills but also assisted women with finding employment. Bharati Roy and Aparna Basu[4] note that,

“In Calcutta, the refugee problem was acute. The relief and rehabilitation committee of the Calcutta branch, which had done splendid work after the Calcutta and Noakhali riots, was very active. A vocational training centre was run in north Calcutta and refugee women were trained as nurse aids, housekeepers, social workers, primary school teachers and canteen workers. Training was also given in adult education, needlework and tailoring, cooking, dyeing and cleaning. An employment bureau was run successfully. At the request of the Bengal government, the All India Women’s Conference also started vocational training of refugee women at Titaghur. About 500 families that settled on the outskirts of Calcutta took advantage of this.” (102)

the Nari Seva Sangha and the Mahila Atma Raksha Samiti also facilitated the showcasing and sale of women’s craftwork through holding regular art and craft exhibitions. In addition, the Government of West Bengal set up the Refugee Handicrafts emporium in Calcutta in 1953, with the aim of “promoting economic rehabilitation of refugee artisans.”

Like the All India Women’s Conference, the Nari Seva Sangha founded by Seeta Chaudhuri in Calcutta in 1944 to provide relief to female victims of the great Bengal famine, also played an active role in offering refugee women vocational training and education. Additionally, it served as a women’s shelter. Self-described as “A place for underprivileged and distressed adult women,” the aim of the Nari Seva Sangha was to “train, rehabilitate and make these girls self-reliant”[5] through imparting skills in batik, block printing, dyeing and weaving, tailoring, embroidery, knitting, toy making, cookery, and food preservation. Both, the Nari Seva Sangha and the Mahila Atma Raksha Samiti also facilitated the showcasing and sale of women’s craftwork through holding regular art and craft exhibitions. In addition, the Government of West Bengal set up the Refugee Handicrafts emporium in Calcutta in 1953, with the aim of “promoting economic rehabilitation of refugee artisans.” [6]

Manikuntala Sen, twice elected to the West Bengal Legislative Assembly, was involved with the work of the Nari Seva Sangha and active in the Mahila Atma Raksha Samiti. In a memoir on her political life Shediner Katha[7], Sen notes the contributions of refugee women from East Bengal in accelerating middle-class Bengali women’s passage to the labor market, with,

“I was often on tour and whenever I boarded a train, I used to run into these women who would travel up and down … I learnt that some were at school, some at college, while others were teaching. … They were not afraid to travel all alone in search of a livelihood. … It was not just their lives; these women were able to take the responsibility for maintaining their entire families. … These women from East Bengal were teachers or nurses or clerks; was there any work that they could not do? They formed the majority of the working women in West Bengal. This is just one example of how women who had once lost everything helped the women of West Bengal enter the job market … Had it not been for the pressures of necessity and numbers, it might not have been possible to push open the doors that had remained closed to women all these years.” (181-82)

Large numbers of middle class Hindu women were engaged in paid employment. This significant reconfiguration in Bengali society did not pass unnoticed in contemporary literature and film. Bengali fiction, beginning in the late-1940s, bears testimony to the changes the Partition wrought in the lives of displaced women, and serves as an important record of the historical experience of the political division. There are many instances: Arati, a door-to-door sales-woman in Narendranath Mitra’s story Abataranika (“The Staircase”; 1949) which was later adapted into film by Satyajit Ray as Mahanagar (The Big City, 1963)[8]; Bina and Kamala, telephone operators in Narendra Mitra’s novel Durabhashini[9] (Lady Telephone Operator, 1952); Neeta, a clerk in Ritwik Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-Capped Star; 1960); Sutara, a college professor in Jyotirmoyee Devi’s Epar Ganga Opar Ganga[10] (trans. The River Churning, 1968); Pushpa a peddler of rag dolls on passenger trains in Samaresh Basu’s Pasharini [11] (“Hawker woman”); or, Nirupama, a school teacher in Dibyendu Palit’s Maachh [12] (“Fish”). Novels and short stories captured the quiet courage of women who, without knowing, or intending to, expanded the horizon of possibilities for Bengali middle-class women—both displaced and non-displaced—making employment outside the home not only socially acceptable, but also, respectable.

For Sutara Datta, in Jyotirmoyee Devi’s 1968-novel Epar Ganga Opar Ganga, education and employment offer means of survival and the possibility of a respectable life away from her estranged family. When Hindus in her East Bengal village are attacked during the Noakhali riots in the autumn of 1946, the adolescent Sutara Datta loses her parents and older sister. A Muslim neighbor, Tamizuddin, finds her unconscious, and brings her to his residence where his family takes care of her. Despite Tamizuddin’s communications with Sutara’s three older brothers in Calcutta, they show little inclination to take her in. Their unwillingness is based on her long stay in a Muslim home and a suspicion of her having been violated during the attack on the village. Nevertheless, on Sutara’s insistence Tamizuddin delivers her to Calcutta to the care of her oldest brother Sanat and his wife Bibha. At this time, all three of Sutara’s brothers and her sister-in-law Bibha are living in the home of Bibha’s parents. The elderly women in the prosperous, upper-caste Hindu household disapprove of Sutara’s presence because they consider her “polluted.” In a move to keep Sutara away, her brothers send her first to a boarding school run by Christians, and later, to live in college dormitories. Sutara is especially unwanted at social events in her extended family and Bibha’s mother’s routine insults reach a peak during a wedding in the family when Sutara is fed separately and hurriedly returned to her hostel at school to protect the other guests from her “polluting” presence. Sutara completes her education and is employed as a lecturer of History at a women’s college in Delhi. She finds accommodations in a hostel for working women.

It is through education and paid employment that Sutara escapes her extended family’s disdain and regular humiliations. Her financial independence also protects her from a possible-future in a government-sponsored Permanent Liability Camp for destitute women. Sutara’s reflections about her living quarters in the women’s hostel dwell on the issue of women’s independence, particularly their economic empowerment: “[I]t was a room of her own, her own place acquired with her earnings. … From now on, her brothers wouldn’t have to provide for her. They wouldn’t even have to spare a thought for her. Has she become independent? Are women ever independent?” (142). Sutara’s autonomy and personal wellbeing are grounded in the economics of ownership – her ownership of her room, her private space made possible by her salary. After being repeatedly moved around at the will of her brothers and the extended family – from her natal village to Calcutta and, then, from the home of her brother Sanat’s in-laws to a boarding school and from there on to college dormitories – her room offers stability. It is a sanctuary for which she is indebted to no one. Within that rented space, Sutara is free.

That said, Epar Ganga Opar Ganga offers an uncommon glimpse into the life of a middle-class woman living outside the family fold. In contrast to the repeated trauma brought upon Sutara by her surviving family who offer no sanctuary, nor show the slightest concern for her wellbeing, the working women’s hostel is a haven of support. Living in the dormitory in Delhi, she transforms from the silent, frightened, and passive adolescent seen earlier in the novel to a bold and lively woman who feels comfortable sharing her past. In the company of other refugee women in the hostel and in her workplace, Sutara is not rebuffed by her listeners but met with friendship. Even though they are aware of her prolonged stay in a Muslim home, her colleagues invite her to attend Hindu religious ceremonies and take her on pilgrimages. In other words, she is absorbed without prejudice into a new form of community. Jyotirmoyee Devi’s novel celebrates the resilience of the women in the hostel while at the same time acknowledging their solitude, “Sutara switched off the lights in her room. Stars sparkled in the dark April sky. At the edges of the garden a few Eucalyptus trees stood straight and tall, apart and lonely. Like the women in the hostel. … Cyclones would bend them but couldn’t break them” (253).

For Sutara Datta, wage-work is the source of her freedom, even empowerment. This sentiment is echoed by many others as well. Speaking to the historian Gargi Chakravartty, Partition refugee Hasna Chowdhury acknowledges that, “Because of Partition we learnt to become self-reliant, and stand on our feet. Without Partition this would not have been possible”[13] (91). For Hasna Chowdhury, like the fictional Sutara, salaried-work was a liberating experience. This was not restricted to the Bengal region alone: For Bibi Inder Kaur, a refugee from Karachi, Pakistan, Partition provided a means of escape from a tradition-bound life. In an interview with Ritu Menon and Kamla Bhasin[14], Inder Kaur spoke from her personal experience regarding how the tumult around the Partition presented women with the possibility of crafting new and different futures for themselves and enabled her, in her words, to “spread [her] wings” (215). In Karachi, her husband “allowed” (213) her to learn embroidery but not to study. However, after migrating to Delhi, Inder Kaur, then a mother of three, and close to forty years of age, begged her husband to allow her to finish her secondary education, “How will it matter? I won’t start reaching for the stars” (213). But she did more than matriculate from school, she eventually completed a Masters degree and became a college professor, and later, the Principal of the college. The Partition, she says,

Provided me with the opportunity to get out of the four walls of my house. I had the will power, the intelligence, Partition gave me the chance. In Karachi, I would have remained a housewife. Personally, I feel Partition forced many people into taking the initiative and finding their own feet. … There are millions of women like me who want to do something but cannot. I managed to because Partition gave me a chance. … I never wanted to go back, back to that life. I had spread my wings. (215)

As I mentioned earlier, not all refugee women were inclined to careers in education and many opted for non-traditional jobs. For instance, refugee women in Narendranath Mitra’s writings such as Arati Majumdar is a door-to-door sales-woman while others like Beena Guhathakurta and Kamala Mukherjee are telephone operators. Prior to the economic catastrophe unleashed by the Partition, both professions would have been shunned by women from Hindu middle-class backgrounds. In Samaresh Basu’s story “Pasharini” (“Hawker-Woman”), Pushpabala peddles hand-made rag dolls to passengers on commuter trains. An eighteen-year-old middle-class migrant, Pushpa and her family have been displaced by Partition from their native village in East Pakistan to the outskirts of Calcutta, where in the absence of a male breadwinner, she assumes responsibility for the upkeep of her widowed mother and younger siblings. But, Pushpa’s only skill is her handiwork – making rag dolls. It pays little, and her work conditions are grim. She encounters hostility from male hawkers, among whom are displaced young men who view her as a threat to their livelihood and mockingly call her “putuler ma” or the “mother of dolls.” She is also subject to disdainful comments from male passengers. And later, as an unlicensed vendor, she is arrested by the police and sentenced to jail for a week.

While Pushpabala takes up this unconventional profession of hawking on trains, her aspirations are entrenched in traditional domestic roles, that of wife and mother, but she knows that her marriage prospects are bleak. Pondering on the name mockingly given to her by her male co-hawkers “mother of dolls,” Pushpa silently agrees that she can only be a “mother of dolls, a female hawker. Not a woman. Without conch bracelets and vermilion. The dolls’ father would never appear amid the music of a pledge of home and protection” (201). Pushpa believes that all she can create are lifeless rag dolls, not living, breathing children.

Yet, she courageously shoulders the responsibility for maintaining the household after the passing away of her father. And it is one she voluntarily accepts. On the day she first sets out to sell the rag dolls, a diffident Pushpa sits alone in an empty train compartment composing herself, firming her resolve:

She saw before her eyes, her widowed mother’s face … and her mind responded, I can do this. She remembered her brothers and sisters, all of them so young, and she thought, I can. Her famished body … and her mind stood before her, the mind responded with, I can, I can. As a gust of wind ruffled her long hair and it slapped against her, an invisible strength flowed from her spine towards her feet, it straightened her bent frame and sprinted back with, I can, I can do this. (195)

Large numbers of middle class Hindu women were engaged in paid employment. This significant reconfiguration in Bengali society did not pass unnoticed in contemporary literature and film. Bengali fiction, beginning in the late-1940s, bears testimony to the changes the Partition wrought in the lives of displaced women, and serves as an important record of the historical experience of the political division.

But unfortunately, that first day, Pushpa loses the nerve to even announce her product to the passengers on the train. However, the following day, although her voice falters a little initially, she soon regains her composure. But when she makes her sales-pitch about her hand-made dolls, the passengers on the train react with “surprise, shame, exasperation, pity and laughter” (198). The passengers who were “skeptical, scrutinized her closely. … No, no way was she a good woman. Hawking on trains! … On the streets at this age … among crowds! There was something fishy about the whole thing” (199). Samaresh Basu, highlights the many odds against which Pushpa has to struggle.

In the cinematic rendition of Basu’s “Pasharini” in 1973, retitled as “Putuler Ma” (“Mother of Dolls”), actress Sabitri Chattopadhyay was selected to play the title role. As I said at the beginning of this presentation, Chattopadhyay’s own fight against starvation was much like Pushpabala’s, and Sabitri Chattopadhyay delivered the part with characteristic skill, illuminating sensitively the plight of the impoverished displaced woman struggling to keep her family afloat. Chattopadhyay notes in Amar Katha that she was selected for the role because of her “refugee-like appearance” (251). In other words, she was undernourished, and, therefore, very slender.

I will wrap up the essay with the words of a woman who also chose a non-traditional career, a career as a professional dancer. Arati Das, better known as Miss Shefali, was Calcutta’s leading cabaret performer during the 1960s and ’70s. In an interview in 2012 to The Telegraph, she spoke about her struggle to protect her displaced family from economic ruin in the wake of the Partition[15]. Aspiring to provide a better life for them, she started paid work as a maid servant while still a child. Later, she took to professional dancing:

“During Partition, my parents left [East Pakistan] and came to Calcutta. We were three sisters and one brother. In Calcutta, we had a few relatives but they were not in a position to give us shelter. … Ma took up the job of a cook at a Bengali household in Ahiritola. They gave us a room to stay. Baba was ill and would stay at home. We would wait for Ma to come back with food. I was the youngest and I wanted to give my parents a good life. There was a nurse who lived next door and I would go to her often and beg her to give me a job. I was only 11 then. One day she told Ma that there was a job for me as a domestic help with an Anglo-Indian family in Chandni Chowk. Ma agreed and I landed there.

The family lived like the Europeans. They would throw parties every day and there would be music and all of them would dance. I would watch them from behind the curtains and practice the moves later. A guy called Vivian Hansen would frequent their house. He was a singer at Mocambo Restaurant then. One day I asked Vivian if he could get me a better job and he asked me if I could dance. I said yes! … He took me to Firpo’s.

At that time Firpo’s was one of the most expensive and fancy hotels in Calcutta. … The manager … asked me to show him some dance moves, and I was hired! I told them they would have to give me a place to live and also give me food. They put me up at a bungalow behind the Great Eastern Hotel. My salary was Rs 700 a month, 10 times more than what I got as a domestic help! … I had foreigners like Gloria coming to the bungalow to teach me dance, from Hawaiian to belly dancing to Blues, Charleston, Can-can, Twist … I had to learn all forms of western dance. I also had a Hindi teacher. …I was only 13 then, too young to understand what was happening. But I knew that I would get good money and get a house for Ma-Baba.“

Towards the end of Ritwik Ghatak’s film Meghe Dhaka Tara or The Cloud Capped Star, a dying Neeta housed in a sanatorium seems to almost plead with her visiting older brother Shankar, “Dada, I will live” (“Dada, ami banchbo”). Her words echo through the hills of Shillong. Her will to live in the face of unforgiving circumstances illuminates the indomitable spirit of displaced women who picked up the pieces of their broken lives and set about re-building new ones in places they had never lived before, and amongst people they had never known—people who had different food habits and spoke a different dialect of Bengali. Young women in migrant middle-class families acquired education and found employment, and their mass participation in salaried labor created a social environment that, with time, grew less averse to women’s work.

The research for this article is taken in part from my book, Literature, Gender, and the Trauma of Partition: The Paradox of Independence. New York and Abingdon, Oxon.: Routledge, 2017. There is also a South Asian edition of this book published by Routledge (New Delhi), 2021.